1. Introduction

Growing urbanization has led to the increasing popularity of high-rise residences [1-2]. As one of the primary structural forms of high-rise residential buildings, the demand for the architectural and structural design of reinforced concrete shear wall structures is significant [3].

In the field of architectural and structural design, methods such as topology optimization and heuristic algorithms are widely used [4-12]. However, these optimization algorithm-based architectural or structural design methods have limitations: precise and explicit definition of optimization objectives, rules, and constraints is often challenging; definition of priorities among different constraints is difficult; and large-scale iterative optimization is often time-consuming. Moreover, optimization algorithms cannot fully utilize the data of existing excellent designs and understand their implicit features. Unlike optimization algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI) methods, such as deep learning methods, can directly learn design experiences from design data and generate new designs efficiently. Deep learning has developed rapidly in recent years and achieved significant applications in many fields [13-16]. For the intelligent layout design of shear wall structures, methods based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) have been developed. Pizarro et al. [17] and Pizarro and Massone [18] applied CNNs to the layout design of shear wall structures. Liao et al. [19] and Lu et al. [20] developed GANs and physics-enhanced GANs to design shear wall structures. AI-based design methods of shear wall structures can learn design experience from existing design data and provide beneficial references for engineers in the preliminary structural design stage.

However, current structural designs based on GANs and CNNs may generate unreasonable local details and cannot thoroughly learn the requirements and constraints of architectural spaces on structural design, which require further improvement. Existing GAN-based design methods of shear wall structures, such as StructGAN [19], have established the global correspondence between architectural and structural designs (that is, the entire planar layout of the building). However, the global correspondence implies that the design attention is evenly distributed on the structural design drawing. Contrarily, human engineers pay greater attention to critical zones while designing structural layouts. Thus, the evenly distributed design attention of StructGAN differs from the actual behavior of human engineers. Moreover, the experience and feedback of engineers on the design results of StructGAN indicated the following: in the vicinity of certain critical zones (such as elevator shafts), shear walls tended to have unique layout characteristics that differed from those in other zones, and the performance of StructGAN on these critical zones was insufficient. Therefore, further research on AI-based design methods is required to improve the local shear wall design of critical zones.

Currently, some studies have modified GANs by introducing methods, such as boundary equilibrium, to improve image generation details [21-24]. However, such improvements in image quality focus on the clarity of the image. In contrast, the design defect of local details in the current shear wall layout design method is not related to image clarity. Actually, the local shear wall layout generated by neural networks for certain critical zones does not meet professional requirements. Therefore, neural networks that focus on the critical zones are necessary such that they can perform intensive learning on the local layout of shear walls. Traditional CNNs and GANs relying on convolution operations [12,19,25-26] due to the limitations of the local receptive field of the convolution operator face challenges in focusing on the local design of the shear wall layout [27]. In contrast, the attention mechanism can enable the neural networks to learn which local region to focus on by considering the dependencies across different image regions [28-31]. Consequently, the development of the attention mechanism in computer vision [27,32-35] has provided new solutions for improving the local layout design of shear wall structures. The self-attention method of the attention mechanism can automatically find the area that the neural networks must focus on during their training without additional input, thus leading to excellent performance in semantic segmentation and image generation [27,33,36-37]. Furthermore, screening and pre-processing of image features through prior knowledge is widely used in computer vision [38-40]. Pre-labeling critical zones of an image with semantic masks is a simple feature engineering that introduces an artificial-attention mechanism. Therefore, this study introduced the self-attention and artificial-attention methods to focus on critical zones, and thereby improve the neural network-based shear wall design method.

In addition to relying on the high quality of data, deep learning-based methods are sensitive to the quantity of data [12,41-43]. The layout characteristics of shear walls under different design conditions are significantly different [3]. Therefore, if the data of shear wall structures under different design conditions are combined in the training dataset, deep learning-based methods cannot effectively learn the layout characteristics of shear walls corresponding to different design conditions [19]. However, if the data of shear wall structures under different design conditions are separated, and the deep learning-based methods are trained under certain design conditions, the data for individual design conditions may be insufficient. This dilemma of neural networks can be improved by pre-training on datasets containing different classes [44-46], which could enhance the generalizability of neural networks using small amounts of data. Therefore, this study adopted the pre-training method and discussed its effect.

In Section 2, the design method for shear wall structures based on attention-enhanced GANs is presented. Section 3 consists of the construction method for the attention-enhanced GANs for shear wall layout design. In Section 4, the performances of different GAN models in shear wall layout design are compared. Section 5 discusses the differences between the design results of different GANs and engineers in the critical zones of shear wall layout design through case studies, and further compares the structural performance.

2. Proposed Design Method for Shear Wall Layout

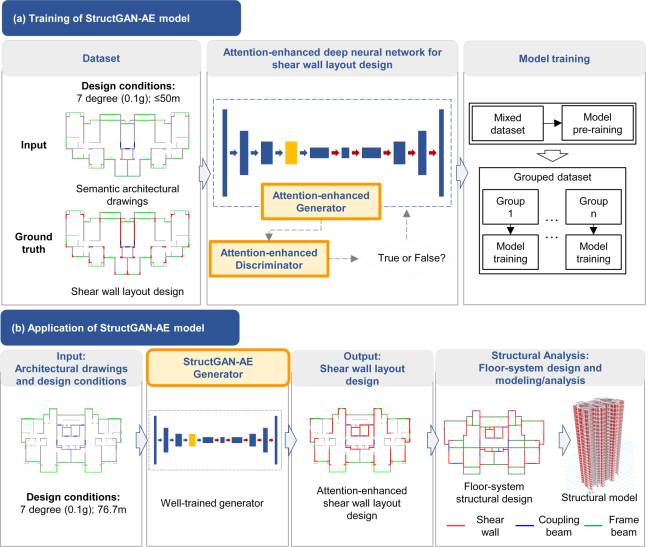

This study proposed a GAN model enhanced using an attention mechanism, named StructGAN-AE, for the intelligent design of shear wall structures. Additionally, a pre-training method was adopted during model training to overcome the shortage of data under different design conditions, as shown in Figure 1. The proposed method consisted of two parts: (1) training of the StructGAN-AE model, and (2) application of the StructGAN-AE model.

(1) Training of StructGAN-AE model.

The design of critical zones in a shear wall layout using the existing GAN-based design methods does not meet the experience of human engineers, and furthermore, it does not meet the requirements and constraints of architectural spaces for structural design. To overcome these design defects, StructGAN-AE adopted two attention mechanisms to enhance GANs: self-attention and artificial-attention mechanisms. Specifically, a self-attention mechanism was introduced to automatically capture the features of the critical zones, such that the local design quality of the shear wall layout in those critical zones could be improved. See Subsection 3.2 for details. Although the self-attention mechanism can automatically focus on critical zones without additional prior information, its performance is limited by the quality and quantity of training data. Therefore, a simple artificial-attention method was introduced, wherein the critical zones of the shear wall structure were labeled with artificial semantic masks. See Subsection 3.3 for details.

A two-stage pre-training method was adopted to enhance the generalizability of neural networks for intelligent structural design, so that they could perform better with smaller data samples corresponding to different design conditions. See Subsection 3.4 for details.

(2) Application of StructGAN-AE model. In this stage, a semantic architectural design image under a specific design condition was input into the generator of the well-trained StructGAN-AE, and the design result of the shear wall layout was obtained. Thereafter, the method proposed by Zhao et al. [47] was adopted to realize the layout design of beams and floor slabs. Subsequently, a finite element model (e.g., the ETABS model) was established for structural analysis. The data transition from the layout design of the shear walls, beams, and floor slabs to the ETABS model can be found in Lu et al. [20] and Zhao et al. [47].

Figure 1 Design method of shear wall layout. (a) training of StructGAN-AE model, and (b) application of StructGAN-AE model

3. Attention-enhanced StructGAN

3.1 StructGAN

Liao et al. [19] proposed StructGAN for the automated design of shear wall structures. High-resolution schematic design images of the shear wall layout can be obtained by inputting semantic architectural drawings into StructGAN. Liao et al. [19] evaluated the design results of StructGAN using the confusion matrix and intersection over union (IoU) methods combined with engineering cases and demonstrated its applicability and high efficiency.

However, according to the experience of professional engineers and feedback from questionnaires of scholars and engineers, certain local shear wall layouts generated by StructGAN do not match the domain experience and constraints of architectural space on the structural design. These local shear wall layout defects are mainly manifested in elevator shafts and balconies (Figure 2), and are listed as follows:

(1) The elevator shaft zone requires sufficient shear walls to satisfy the structural load-bearing and lateral force-resisting performance requirements. However, the design results of StructGAN showed fewer shear walls and evidently unreasonable discontinuities.

(2) In the balcony zone, shear walls are rarely arranged on the periphery. However, the design results of the StructGAN showed shear walls arranged in the balcony zone.

Figure 2 Design defects of StructGAN in the shear wall layout scheme, ① is the elevator shaft zone, and ② is the balcony zone.

3.2 Self-attention StructGAN

A self-attention mechanism named SAGAN was proposed by Zhang et al. [27]. It enhances the ability of GANs to learn the correlation between different discrete spatial regions by introducing self-attention layers in the generator and discriminator so that they can autonomously learn which local features must be focused. Equations (1) to (3) show its core calculation equations [27].

|

|

(1) |

|

|

|

(2) |

|

|

|

(3) |

where, C is the number of channels, and N is the number of feature locations; the input to the self-attention layer are features x∈RC×N from the previously hidden layer of the self-attention layer in the GAN, and the output is o∈RC×N; Wf∈RC’×C,Wg∈RC’×C,Wh∈RC’×C, and Wv∈RC×C’ are learnable weight matrices, implemented as 1×1 convolutions; C’=C/8 according to Zhang et al. [27].

As per Zhang et al. [27], self-attention layers were added to the generator and discriminator of StructGAN. Specifically, in the generator, a self-attention layer was added after n_downsample_global down-sampling convolution operations, as shown in Figure 3(a). The discriminators were multi-scale discriminators, and each discriminator was an N-layer discriminator [48] based on the patch-based fully convolutional network [48-49]. After the n_layers_D convolutions of each N-layer discriminator, a self-attention layer was added, as shown in Figure 3(b).

Figure 3 Network-architecture schematic of generator and discriminator: (a) generator, and (b) N-layer discriminator.

Both n_downsample_global and n_layers_D were parameters in StructGAN. The positions of these self-attention layers comprehensively considered the balance between the parameter size of the model and the effectiveness of the attention mechanism. The above-mentioned self-attention method generates dense pixel-by-pixel dependencies for the features acted on by the attention layer, which consumes a lot of GPU memory and computing resources. Therefore, for the high-resolution shear wall design images of this study, performing self-attention feature operations directly on high-resolution features would consume a tremendous amount of computing resources, which is almost infeasible in practical applications. Contrarily, the convolution operation compresses the feature resolution; hence, performing the self-attention feature calculation after the convolution operation performs down-sampling compression on the image features is appropriate.

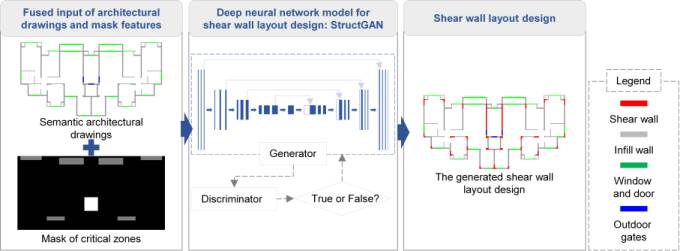

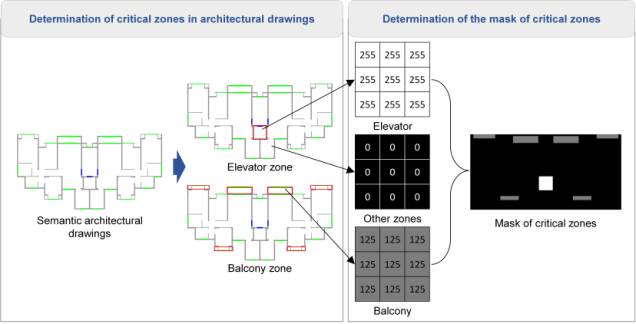

3.3 Artificial-attention StructGAN

StructGAN faces difficulties with the local shear wall layout near elevator shafts and balconies. Therefore, in this study, the elevator shaft and balcony zones were artificially selected as the critical zones. Resultantly, the artificial-attention StructGAN was proposed. Specifically, the critical zones (e.g., elevator shafts and balconies) were pre-annotated using semantic masks. Subsequently, the mask and architectural design were simultaneously used as inputs for the artificial-attention StructGAN. Consequently, the artificial-attention StructGAN could learn the local design features in the critical zones through the artificial semantic mask. Figure 4 shows the schematic of the construction method of the artificial-attention StructGAN.

Figure 4 Schematic of artificial-attention StructGAN

In this study, the mask of the critical zones was a semantic grayscale pixel tensor consistent with the dimensions of the architectural drawing. The elevator shaft zones, balcony zones, and rest zones were denoted with the integers 255, 125, and 0, respectively, as shown in Figure 5. In the neural network training and subsequent applications, the mask tensors of the critical zones and the semantic architectural images were directly concatenated in the channel dimension and input into the artificial-attention StructGAN.

Figure 5 Determination of mask features of critical zones

3.4 Pre-training Based on Shear Wall Dataset with Different Groups

Liao et al. [19] divided the data of shear wall structures into three design condition groups, namely Group7-H1, Group7-H2, and Group8. The shear wall structures in Group7-H1 correspond to a 7-degree seismic design intensity, that is, peak ground acceleration (PGA) of 100 cm/s2 with a 10% probability of exceedance in 50 years, and a structure height ≤ 50 m. The shear wall structures in Group7-H2 correspond to a 7-degree seismic design intensity and structure height > 50 m. The shear wall structures in Group8 correspond to an 8-degree seismic design intensity, that is, PGA of 200 cm/s2 with a 10% probability of exceedance in 50 years. This study adopted the same dataset and semantic method as Liao et al. [19] and used Group7-H1, Group7-H2, and Group8 to divide the data of the shear wall structures into three design condition groups. Specifically, there are 63, 80, and 81 training sets and 8, 8, and 8 testing sets in Group7-H1, Group7-H2, and Group8, respectively.

Liao et al. [19] showed that dividing the data of shear wall structures into three groups (i.e., Group7-H1, Group7-H2, and Group8) and training StructGAN using different groups could better incorporate the effects of different heights and seismic design intensities on the shear wall layouts. However, each group consisted of less than 90 architectural-structural drawing pairs, which hindered the performance of neural network training. Therefore, this study explored pre-trained models. Specifically, the following two-stage training strategy was adopted for the three neural networks (StructGAN, self-attention StructGAN, and artificial-attention StructGAN):

Stage 1: Pre-training. Based on the mixed data of all three groups, the neural network model was trained to obtain a pre-trained model.

Stage 2: Individual training. The pre-trained model was then trained individually for each group to further learn the characteristics of different groups.

As a result, based on the three neural networks (StructGAN, self-attention StructGAN, and artificial-attention StructGAN) and the two training strategies (with or without the pre-training stage), this study discussed the following six models, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Six models discussed in this study

|

Neural network |

Pre-training stage |

|

|

StructGAN |

StructGAN [19] |

Without pre-training stage |

|

StructGAN-SA |

Self-attention StructGAN |

Without pre-training stage |

|

StructGAN-AA |

Artificial-attention StructGAN |

Without pre-training stage |

|

StructGAN-PT |

StructGAN [19] |

With pre-training stage |

|

StructGAN-SA-PT |

Self-attention StructGAN |

With pre-training stage |

|

StructGAN-AA-PT |

Artificial-attention StructGAN |

With pre-training stage |

4. Performance of Attention-enhanced StructGAN

Various methods are employed for evaluating design performance. Since the preference of the structural design scheme is a complex issue that comprehensively considers many factors, such as structural performance, construction cost, and construction convenience, real-world projects often rely on the accumulated experience of excellent engineers. Therefore, this study aims to align the design results of AI with those of engineers as much as possible. Specifically, this section will preliminarily compare the differences in shear wall layout between the AI’s and the engineers’ designs based on computer graphics methods. Section 5 further compared the differences in structural performance between the designs of the AI and engineers through more detailed structural analyses.

The computer graphics-based consistency evaluation metric used herein is ScoreIoU, as shown in Equations (4) to (8) [19]. ScoreIoU can synthesize image similarity and shear wall ratio similarity between the designs from the AI and engineers.

|

|

(4) |

|

|

|

(5) |

|

|

|

(6) |

|

|

|

(7) |

|

|

|

(8) |

where, SWratio represents the shear wall ratio; SWratioGAN and SWratiotarget represent the shear wall ratio of GAN’s design and target design, respectively, calculated using the ratio of the shear wall area Aswall and the sum of shear wall area Aswall and infill wall area Ainwall in the design result; SIoU is the IoU of shear walls; ASWinter is the shear wall intersection area of GAN’s design and target design, and ASWunion is the shear wall union area where ASWunion = ASWtarget + ASWGAN − ASWinter; ASWtarget and ASWGAN are shear wall areas for target design and GAN’s design, respectively; WIoU is the weighted IoU; (k+1) is the class number, and this study focused on 5 classes (class 0 represents the background, class 1 represents the shear wall, class 2 represents the infill wall, class 3 represents the window and door, and class 4 represents the outdoor gates); pij is the pixel that belongs to class i but is predicted to be in class j; w0=0, w1=0.4, w2=0.4, w3=0.1, and w4=0.1; ηSWratio denotes the correction coefficient for the overall quantity of shear walls; ηSIoU and ηWIoU are the weight coefficients of SIoU and WIoU, respectively, and both are 0.5.

Previous studies have shown that IoU > 0.5, indicating that the neural network results were highly consistent with the target value [50-52]. ScoreIoU is a weighted indicator based on IoU metrics, and a ScoreIoU greater than 0.5 indicates that the design results are of high quality [19]. This study compared the performance of StructGAN and StructGAN-AE, as shown in Table 2. In addition to the comprehensive evaluation metric ScoreIoU, the SIoU and 1−ηSWratio metrics are important. SIoU is the IoU of shear walls and represents the similarity between the shear wall layouts designed by the AI and engineers. 1−ηSWratio represents the difference in the shear wall ratio between the designs by the AI and engineers. Generally, larger ScoreIoU and SIoU, and smaller 1−ηSWratio are preferred.

As shown in Table 2, for Group7-H1, the ScoreIoU of StructGAN-AA-PT (0.52) was the best, which was 30% higher than that of StructGAN (0.40) and exceeded 0.5. For Group7-H2 and Group8, the optimal model was StructGAN-SA-PT, and ScoreIoU was improved by 0.05 compared with StructGAN. For Group7-H2, ScoreIoU of StructGAN-SA-PT (0.57) was 9.6% greater than that of StructGAN (0.52). For Group8, ScoreIoU of StructGAN-SA-PT (0.70) was 7.7% greater than that of StructGAN (0.65).

The combination of attention-enhancing and pre-training methods exhibited the best performance. ScoreIoU values of the two attention-enhanced StructGAN models with the pre-training method (i.e., StructGAN-SA-PT and StructGAN-AA-PT) were the two highest in each design condition group, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Comparison of metrics of StructGAN-AE and StructGAN

|

Test set |

Metrics |

StructGAN |

StructGAN |

StructGAN |

StructGAN |

StructGAN |

StructGAN |

|

Group7 |

SIoU |

0.41 |

0.52 |

0.55 |

0.49 |

0.58 |

0.60 |

|

WIoU |

0.59 |

0.60 |

0.61 |

0.57 |

0.64 |

0.67 |

|

|

SWratiotarget |

0.41 |

||||||

|

SWratioGAN |

0.50 |

0.52 |

0.57 |

0.45 |

0.53 |

0.48 |

|

|

1−ηSWratio |

20% |

27% |

28% |

20% |

23% |

19% |

|

|

ScoreIoU |

0.40 |

0.41 |

0.43 |

0.44 |

0.48 |

0.52 |

|

|

Group7 |

SIoU |

0.58 |

0.64 |

0.65 |

0.64 |

0.64 |

0.68 |

|

WIoU |

0.63 |

0.62 |

0.62 |

0.54 |

0.63 |

0.64 |

|

|

SWratiotarget |

0.58 |

||||||

|

SWratioGAN |

0.66 |

0.63 |

0.68 |

0.85 |

0.63 |

0.72 |

|

|

1−ηSWratio |

14% |

15% |

15% |

32% |

10% |

19% |

|

|

ScoreIoU |

0.52 |

0.54 |

0.54 |

0.41 |

0.57 |

0.54 |

|

|

Group8 |

SIoU |

0.74 |

0.77 |

0.77 |

0.71 |

0.80 |

0.78 |

|

WIoU |

0.72 |

0.70 |

0.70 |

0.56 |

0.74 |

0.71 |

|

|

SWratiotarget |

0.66 |

||||||

|

SWratioGAN |

0.76 |

0.75 |

0.76 |

0.91 |

0.72 |

0.73 |

|

|

1−ηSWratio |

13% |

13% |

13% |

27% |

9% |

10% |

|

|

ScoreIoU |

0.65 |

0.66 |

0.65 |

0.48 |

0.70 |

0.67 |

|

The pre-training method significantly improved the performance of attention-enhanced StructGAN. Solely considering attention enhancement without pre-training methods was insufficient. In each design condition group, ScoreIoU values of the two models that only considered attention enhancement (i.e., StructGAN-SA and StructGAN-AA) were slightly improved, and did not exceed 0.03. Specifically, for Group7-H1 and Group7-H2, SIoU of StructGAN-SA and StructGAN-AA were improve. However, compared with the engineers’ design, excessive shear walls were generated by StructGAN-SA and StructGAN-AA, which increased the 1−ηSWratio. It is worth noting that ScoreIoU was an indicator that comprehensively considered the shear wall ratio and component similarity, thus the improvement in ScoreIoU of StructGAN-SA and StructGAN-AA was not evident. For Group8, the metrics of StructGAN-SA and StructGAN-AA were close to that of the original StructGAN.

Furthermore, adopting the pre-training method without considering the attention mechanism was insufficient. The StructGAN-PT using the pre-training method exhibited unstable performance in different groups. Specifically, for Group7-H1, ScoreIoU of StructGAN-PT was improved compared to that of the original StructGAN. Nevertheless, for Group7-H2 and Group8, the shear wall ratio of StructGAN-PT was excessively high, and ScoreIoU was significantly reduced.

For Group7-H1, the optimal model was StructGAN-AA-PT. However, for Group7-H2 and Group8, the optimal model was StructGAN-SA-PT. Figure 6 shows two representative cases of Group7-H1 and Group8. For Group7-H1, in the elevator shaft zones, the design generated by StructGAN exhibited fewer shear walls, and the shear wall had an evident discontinuity (e.g., elevator shaft zone ② in Figure 6(a)). In the balcony zones, StructGAN placed too many shear walls. Contrarily, no shear wall was arranged on the balcony periphery in the engineers’ design (e.g., balcony zone ① in Figure 6(a)). Unlike StructGAN, StructGAN-AA-PT improved the layout design of shear walls in the elevator shaft and balcony zones. Moreover, compared with StructGAN, the continuity of the shear wall of StructGAN-AA-PT was improved (Figure 6(a)). For Group7-H2 and Group8, both StructGAN and StructGAN-SA-PT generated excellent shear wall layouts in the elevator shaft zones. However, compared with StructGAN, StructGAN-SA-PT improved the layout design of the shear walls in the balcony zones (e.g., balcony zones in ① and ③ in Figure 6(b)), and moved the shear wall ratio closer to that of the engineers’ design.

Figure 6 Typical test set designs by different StructGAN models: (a) Group7-H1 and (b) Group8.

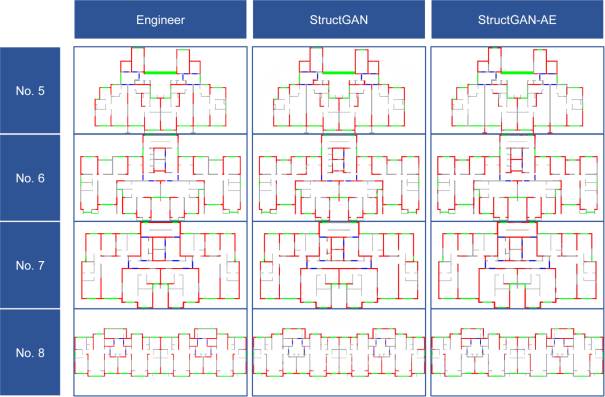

5. Comparison of Structural Performance

This study conducted an in-depth structural analysis and compared the performances of different design schemes. A total of 12 cases in the test set were selected for structural performance analysis, of which 4 belonged to Group7-H1, 4 belonged to Group7-H2, and 4 belonged to Group8. The 4 cases belonging to Group7-H1 (7-degree seismic design intensity, height ≤ 50 m) were all 15 floors and 44.25-m high. The 4 cases belonging to Group7-H2 (7-degree seismic design intensity, height > 50 m) were all 26 floors and 76.7-m high. Among the 4 cases belonging to Group8 (8-degree seismic design intensity), 3 cases were 20 floors and 59-m high, and one was 15 floors and 44.25-m high.

Each structural case corresponded to three design schemes: engineers’ design, StructGAN design, and StructGAN-AE design. According to the previous discussion, for Group7-H1, StructGAN-AA-PT was adopted, and for Group7-H2 and Group8, StructGAN-SA-PT was adopted. When the layout and section dimension designs were completed, finite element models were established using the widely used software, ETABS.

Comparisons of the shear wall layout details corresponding to engineers, StructGAN, and StructGAN-AE of the 12 cases are shown in Appendix A. Figure 7(a) shows a typical case. Compared with StructGAN, StructGAN-AE significantly improved the local shear wall layout details.

(1) In the elevator shaft zone ②, StructGAN-AE can arrange more continuous shear walls and ensure a sufficient shear wall ratio. According to engineers, elevator shafts are often located in the center of the building plane, and the wall is vertically continuous. Therefore, the elevator shaft zone is often suitable for arranging more shear walls, and the continuity of the shear walls also enhances shear resistance.

(2) In balcony zones ④ and ⑥, compared with StructGAN, StructGAN-AE can arrange shear walls that agree with the engineers’ experience; that is, no shear walls are arranged on the periphery of the balcony.

(3) Compared to StructGAN, StructGAN-AE’s shear wall layout scheme has better continuity in other areas. These continuous shear walls are often arranged at the intersection of wall piers, which is usually the critical location for structural component connections. The shear wall layout of the StructGAN-AE can ensure the integrity of the overall structure and is more in line with engineers’ experience.

Figure 7 Typical structure case of Group7-H1. (a) Shear wall layout details corresponding to engineers, StructGAN, and StructGAN-AE; (b) Floor layouts.

After generating the shear wall layout, the frame and coupling beams were designed using the intelligent beam design method proposed by Zhao et al. [47], as shown in Figure 7(b). The dimensions of the shear walls, floor slabs, coupling beams, and frame beams were determined according to the methods of Lu et al. [20] and Zhao et al. [47]. Then, a finite element model was established, and the dynamic characteristics, seismic performance, and material consumption of the structure were analyzed.

A comparison of the torsional period ratio (the ratio of the first torsional natural vibration period to the first translational natural vibration period) for the 12 structural cases is presented in Figure 8. Each translational direction has a first translational natural vibration period.

As shown in Figure 8, the design results of StructGAN-AE exhibit better anti-torsion performance than those of StructGAN. Specifically, two cases designed by StructGAN (both cases belong to Group7-H2) have torsional period ratios greater than 1.0, which exceed the specification requirements and are not recommended in the design of shear wall structures [53-54]. In contrast, in the design results of StructGAN-AE, all torsional period ratios satisfied the specification. Moreover, as shown in Figure 8(c), for different design condition groups, the average torsional period ratio of the StructGAN-AE design results is smaller than that of StructGAN, which indicates that the design results of StructGAN-AE exhibit better anti-torsion performance.

Detailed comparisons of the maximum inter-story drift ratios and the first three natural vibration periods of the 12 cases are shown in Appendix B. The design results of StructGAN-AE are closer to those of engineers. For each structural case, although there were differences between the design of the engineers, the StructGAN design, and the StructGAN-AE design, none of them exceeded the specification limit of 0.001 [53]. Figure 9(a) shows the average difference in the maximum inter-story drift ratio between the design results of the two AI models (StructGAN and StructGAN-AE) and the engineers’ design results, and Figure 9(b) shows the average difference in the first three natural vibration periods. The maximum inter-story drift ratios and the first three natural vibration periods of the design results of StructGAN-AE are closer to those of the engineers’ designs than those of StructGAN. Therefore, compared with StructGAN, StructGAN-AE can better learn the characteristics of engineers’ designs from the design drawing dataset and can better capture the structural dynamic features contained in the drawings.

Figure 8 Torsional period ratios of design results of neural network models and that of engineers: (a) minimum torsional period ratios of 12 structure cases, (b) maximum torsional period ratios of 12 structure cases, and (c) average torsional period ratios of 3 design condition groups

Figure 9 Difference in structural performance between design results of neural network models and those of engineers for 3 design condition groups: (a) difference of maximum inter-story drift ratios and (b) difference of first three natural vibration periods.

A comparison of the concrete and steel consumption for the 12 cases is presented in Table 3. Figure 10 also shows the difference in material consumption for StructGAN and StructGAN-AE compared with the engineers’ design results. The average difference between the material consumption of the StructGAN-AE design results and the engineers’ design results (4.1% for concrete and 3.5% for steel) was smaller than the average difference between the design results of StructGAN and engineers (8.3% for concrete and 7.1% for steel). This conclusion also applies to the average material consumption for each design condition group. Furthermore, in most cases, the design results of StructGAN-AE consume less concrete and steel compared to the StructGAN design results.

Table 3 Material consumption of 12 structure cases under different design models

|

Group7-H1 |

Concrete consumption (m3) |

Steel consumption (ton) |

||||||

|

Case number |

No.1 |

No.2 |

No.3 |

No.4 |

No.1 |

No.2 |

No.3 |

No.4 |

|

Engineer |

696.6 |

674.6 |

782.7 |

1888.7 |

110.1 |

104.7 |

123.9 |

273.6 |

|

StructGAN |

772.4 |

718.7 |

833.1 |

1957.3 |

132.9 |

120.8 |

137.9 |

296.8 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

756.4 |

761.3 |

784.7 |

1858.8 |

118.0 |

124.1 |

128.3 |

284.3 |

|

Group7-H2 |

Concrete consumption (m3) |

Steel consumption (ton) |

||||||

|

Case number |

No.5 |

No.6 |

No.7 |

No.8 |

No.5 |

No.6 |

No.7 |

No.8 |

|

Engineer |

2527.2 |

2770.0 |

3617.6 |

3965.0 |

394.7 |

441.2 |

495.6 |

608.1 |

|

StructGAN |

2748.2 |

3413.5 |

3651.4 |

3955.6 |

411.9 |

533.3 |

529.5 |

652.8 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

2458.3 |

3446.6 |

3579.4 |

3654.3 |

383.7 |

518.5 |

498.8 |

583.1 |

|

Group8 |

Concrete consumption (m3) |

Steel consumption (ton) |

||||||

|

Case number |

No.9 |

No.10 |

No.11 |

No.12 |

No.9 |

No.10 |

No.11 |

No.12 |

|

Engineer |

6970.5 |

4113.3 |

869.3 |

4399.7 |

1090.2 |

650.8 |

155.2 |

651.3 |

|

StructGAN |

7669.1 |

4352.5 |

1122.8 |

4837.1 |

1083.6 |

677.5 |

192.7 |

692.4 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

7500.0 |

4139.4 |

968.3 |

4716.4 |

1091.7 |

673.1 |

180.6 |

694.4 |

|

Overall average |

Concrete consumption (m3) |

Steel consumption (ton) |

||||||

|

Engineer |

2772.9 |

425.0 |

||||||

|

StructGAN |

3002.7 |

455.2 |

||||||

|

StructGAN-AE |

2885.3 |

439.9 |

||||||

Figure 10 Difference in material consumption between design results of neural network models and those of engineers: (a) difference of concrete consumption for 12 cases, (b) difference of steel consumption for 12 cases, (c) difference of concrete consumption for 3 design condition groups and (d) difference of steel consumption for 3 design condition groups.

It should be noted that the engineering design drawings selected in this study are all completed by high-level design institutes and are excellent solutions that comprehensively consider the structural performance, construction cost, and construction convenience. Therefore, this research aims to ensure that the AI’s design results are as close as possible to the results designed by engineers. The structural properties of the design results can be further optimized through optimization algorithms, given that the time is permitted, and the optimization algorithms can fully consider factors such as structural performance, construction cost, and construction convenience.

The above comparisons of torsion period ratios, maximum inter-story drift ratios, natural vibration periods, and material consumption show that compared with StructGAN, the attention-enhanced shear wall design model proposed in this study has better torsional resistance and less material consumption. Meanwhile, the design results have structural performance indicators closer to the engineers’ design results.

6. Conclusion

This study proposed an attention-enhanced GAN model for the intelligent design of shear wall structures, that is, StructGAN-AE, to address the problem of local design defects in current automatic shear wall layout methods based on GANs. A pre-training method was simultaneously adopted to overcome the data shortage under different design conditions. Compared with existing methods, the proposed StructGAN-AE significantly improved the local shear wall design and performed better in comprehensive evaluation metrics and structural performance. The detailed conclusions are as follows.

(1) The introduction of the attention mechanism enabled StructGAN-AE better to capture the shear wall layout features in critical zones, and the pre-training method overcame the limitation of data shortage. StructGAN-AE combined with the pre-training method not only showed a more reasonable local shear wall layout in critical zones but also had the highest comprehensive evaluation metric ScoreIoU.

(2) In the case studies, compared with StructGAN, the design result of StructGAN-AE exhibited better anti-torsion performance. The maximum inter-story drift ratios, natural vibration periods, and material consumption of the StructGAN-AE design were closer to the engineers’ design results.

(3) The concrete consumption of the StructGAN-AE designs was reduced by an average of 3.9% compared with StructGAN’s designs, and the steel consumption of the StructGAN-AE designs was reduced by an average of 3.4% compared with StructGAN’s designs. The reduction in material consumption indicated that StructGAN-AE demonstrated better economic benefits than StructGAN.

It is worth noting that although this study considers the elevator shaft and balcony zones as critical zones, the proposed attention-enhanced method is not limited to these two zones. The local designs of other critical zones can be improved using the proposed method.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Pengju Zhao: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Wenjie Liao: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Yuli Huang: Writing - review & editing. Xinzheng Lu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Shear Wall Layout Details of 12 Cases

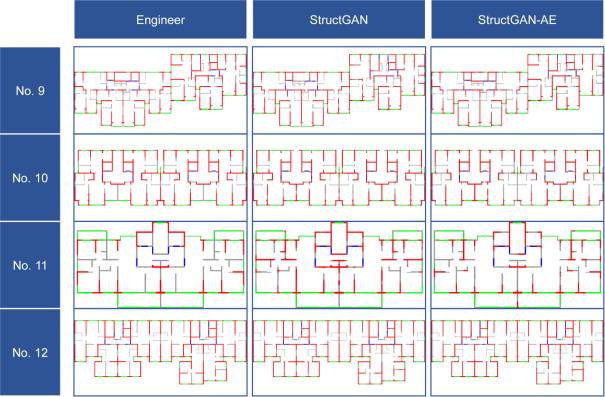

Comparisons of the shear wall layout details corresponding to engineers, StructGAN, and StructGAN-AE of the 12 cases are shown in Figures A.1, A.2 and A.3.

Figure A.1 Shear wall layout details of Group7-H1

Figure A.2 Shear wall layout details of Group7-H2

Figure A.3 Shear wall layout details of Group8

Appendix B. Maximum Inter-story Drift Ratios and Periods of 12 Cases

The maximum inter-story drift ratios and the first three natural vibration periods for the 12 cases in Section 5 are listed in Tables B.1 and B.2, respectively.

Table B.1 Maximum inter-story drift ratios of 12 cases using different design models

|

Group7-H1 |

No.1 |

No.2 |

No.3 |

No.4 |

||||

|

Direction |

x |

y |

x |

y |

x |

y |

x |

y |

|

Engineer |

0.00035 |

0.00053 |

0.00046 |

0.00041 |

0.00029 |

0.00039 |

0.00043 |

0.00034 |

|

StructGAN |

0.00022 |

0.00035 |

0.00034 |

0.00041 |

0.00023 |

0.00031 |

0.00023 |

0.00045 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

0.00028 |

0.00041 |

0.00033 |

0.00034 |

0.00025 |

0.00031 |

0.00032 |

0.00043 |

|

Group7-H2 |

No.5 |

No.6 |

No.7 |

No.8 |

||||

|

Direction |

x |

y |

x |

y |

x |

y |

x |

y |

|

Engineer |

0.00046 |

0.00044 |

0.00036 |

0.00046 |

0.00018 |

0.00028 |

0.00029 |

0.00040 |

|

StructGAN |

0.00030 |

0.00030 |

0.00018 |

0.00036 |

0.00025 |

0.00033 |

0.00016 |

0.00052 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

0.00040 |

0.00039 |

0.00024 |

0.00037 |

0.00023 |

0.00034 |

0.00036 |

0.00062 |

|

Group8 |

No.9 |

No.10 |

No.11 |

No.12 |

||||

|

Direction |

x |

y |

x |

y |

x |

y |

x |

y |

|

Engineer |

0.00049 |

0.00052 |

0.00045 |

0.00055 |

0.00072 |

0.00085 |

0.00031 |

0.00046 |

|

StructGAN |

0.00037 |

0.00049 |

0.00045 |

0.00041 |

0.00041 |

0.00057 |

0.00029 |

0.00042 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

0.00042 |

0.00052 |

0.00041 |

0.00056 |

0.00057 |

0.00075 |

0.00032 |

0.00043 |

Table B.2 Periods of 12 cases using different design models

|

Group7-H1 (s) |

No.1 |

No.2 |

No.3 |

No.4 |

||||||||

|

Order |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

|

Engineer |

1.11 |

0.98 |

0.74 |

1.21 |

1.03 |

0.83 |

0.94 |

0.80 |

0.68 |

1.17 |

0.96 |

0.75 |

|

StructGAN |

0.94 |

0.62 |

0.54 |

0.94 |

0.92 |

0.67 |

0.83 |

0.65 |

0.49 |

0.89 |

0.87 |

0.61 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

0.95 |

0.78 |

0.61 |

0.91 |

0.84 |

0.59 |

0.91 |

0.76 |

0.53 |

0.99 |

0.93 |

0.71 |

|

Group7-H2 (s) |

No.5 |

No.6 |

No.7 |

No.8 |

||||||||

|

Order |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

|

Engineer |

1.64 |

1.59 |

0.96 |

1.94 |

1.61 |

1.50 |

1.27 |

0.89 |

0.62 |

1.71 |

1.40 |

1.37 |

|

StructGAN |

1.34 |

1.24 |

0.73 |

1.39 |

1.05 |

0.82 |

1.39 |

1.08 |

0.85 |

1.85 |

0.95 |

0.79 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

1.76 |

1.54 |

1.11 |

1.42 |

1.11 |

0.83 |

1.34 |

1.09 |

0.74 |

2.00 |

1.90 |

1.19 |

|

Group8 (s) |

No.9 |

No.10 |

No.11 |

No.12 |

||||||||

|

Order |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

|

Engineer |

0.91 |

0.84 |

0.80 |

0.87 |

0.79 |

0.55 |

1.08 |

1.00 |

0.63 |

0.74 |

0.59 |

0.53 |

|

StructGAN |

0.71 |

0.68 |

0.56 |

0.87 |

0.75 |

0.60 |

0.75 |

0.59 |

0.53 |

0.70 |

0.56 |

0.51 |

|

StructGAN-AE |

0.76 |

0.71 |

0.59 |

0.83 |

0.78 |

0.61 |

0.84 |

0.77 |

0.60 |

0.72 |

0.60 |

0.51 |

Reference

[1] CTBUH, Tall buildings in 2019: another record year for supertall completions, CTBUH Research, 2019. https://www.skyscrapercenter.com/research/CTBUH_ResearchReport_2019YearInReview.pdf

[2] R. Perez, A. Carballal, J.R. Rabuñal, M.D. García-Vidaurrázaga, O.A. Mures, Using AI to simulate urban vertical growth, CTBUH Journal, Issue III, 2019. https://global.ctbuh.org/resources/papers/download/4212-using-ai-to-simulate-urban-vertical-growth.pdf

[3] J.R. Qian, Z.Z. Zhao, X.D. Ji, L.P. Ye, Design of tall building structures, Third Edition, China Architecture & Building Press, 2018 (in Chinese)

[4] R. Kicinger, T. Arciszewski, K.D. Jong, Evolutionary computation and structural design: a survey of the state-of-the-art, Comput. Struct. 83 (2005) 1943–1978, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2005.03.002

[5] A.J. Torii, R.H. Lopez, L.F.F. Miguel, Design complexity control in truss optimization, Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 54 (2016) 289–299, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-016-1403-8

[6] J. Liu, S. Li, C. Xu, Z. Wu, N. Ao, F. Chen, Automatic and optimal rebar layout in reinforced concrete structure by decomposed optimization algorithms, Autom. Constr. 126 (2021) 103655, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103655

[7] C.M. Herr, R.C. Ford, Cellular automata in architectural design: from generic systems to specific design tools, Autom. Constr. 72 (2016) 39–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2016.07.005

[8] M. Aldwaik, H. Adeli, Cost optimization of reinforced concrete flat slabs of arbitrary configuration in irregular high-rise building structures, Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 54 (2016) 151–164. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-016-1483-5

[9] S. Sotiropoulos, G. Kazakis, N.D. Lagaros, Conceptual design of structural systems based on topology optimization and prefabricated components, Comput. Struct. 226 (2020) 106136, http://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPSTRUC.2019.106136

[10] S. Tafraout, N. Bourahla, Y. Bourahla, A. Mebarki, Automatic structural design of RC wall-slab buildings using a genetic algorithm with application in BIM environment, Autom. Constr. 106 (2019) 102901, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.102901

[11] H. Lou, B. Gao, F. Jin, Y. Wan, Y. Wang, Shear wall layout optimization strategy for high-rise buildings based on conceptual design and data-driven tabu search, Comput. Struct. 250 (2021) 106546, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2021.106546

[12] S.J. Russell, P. Norvig, Artificial intelligence: a modern approach, Fourth Edition, Hoboken: Pearson, 2021, http://aima.cs.berkeley.edu/

[13] C. Xiong, Q.S. Li, X.Z. Lu, Automated regional seismic damage assessment of buildings using an unmanned aerial vehicle and a convolutional neural network, Autom. Constr. 109 (2020) 102994, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.102994

[14] H. Salehi, R. Burgueño, Emerging artificial intelligence methods in structural engineering, Eng. Struct. 171 (2018) 170–189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.05.084

[15] C. Sun, F. Zhang, P. Zhao, X. Zhao, Y. Huang, X.Z. Lu, Automated simulation framework for urban wind environments based on aerial point clouds and deep learning. Remote Sens. 13 (2021) 2383, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13122383

[16] H. Sun, H.V. Burton, H. Huang, Machine learning applications for building structural design and performance assessment: state-of-the-art review, J. Build. Eng. 33 (2021) 101816, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101816

[17] P.N. Pizarro, L.M. Massone, F.R. Rojas, R.O. Ruiz, Use of convolutional networks in the conceptual structural design of shear wall buildings layout, Eng. Struct. 239 (2021) 112311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112311

[18] P.N. Pizarro, L.M. Massone, Structural design of reinforced concrete buildings based on deep neural networks, Eng. Struct. 241 (2021) 112377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112377

[19] W.J. Liao, X.Z. Lu, Y.L. Huang, Z. Zheng, Y.Q. Lin, Automated structural design of shear wall residential buildings using generative adversarial networks, Autom. Constr. 132 (2021) 103931, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103931

[20] X.Z. Lu, W.J. Liao, Y. Zhang, Y.L. Huang, Intelligent generative design of shear wall structures using physics-informed generative adversarial networks, Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3632

[21] D. Berthelot, T. Schumm, L. Metz, L, BEGAN: Boundary equilibrium generative adversarial networks, 2017, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1703.10717

[22] P. Kancharla, S. S. Channappayya, Improving the visual quality of generative adversarial network (GAN)-generated images using the multi-scale structural similarity index, In: 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 2018, pp. 3908–3912, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2018.8451296

[23] X. Wang, K. Yu, S. Wu, J. Gu, Y. Liu, C. Dong, Q. Yu, C. L. Chen, ESRGAN: Enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks, In: Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) workshops, 2018, pp. 63–79, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11021-5_5

[24] A. Brock, J. Donahue, K. Simonyan, Large scale GAN training for high fidelity natural image synthesis, In: International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2019, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1809.11096

[25] I.J. Goodfellow, J. Pouget-Abadie, M. Mirza, B. Xu, D. Warde-Farley, S. Ozair, et al., Generative adversarial networks, In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2, 2014, pp. 2672–2680, https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/2969033.2969125

[26] S. Albawi, T.A. Mohammed, S. Al-Zawi, Understanding of a convolutional neural network, In: 2017 International Conference on Engineering and Technology (ICET), 2017, pp. 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEngTechnol.2017.8308186

[27] H. Zhang, I. Goodfellow, D. Metaxas, A. Odena, Self-attention generative adversarial networks, In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2019, pp. 7354–7363, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1805.08318

[28] K. Xu, J. Ba, R. Kiros, K. Cho, A.C. Courville, R. Salakhutdinov, R.S. Zemel, Y. Bengio, Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention, In: ICML 2015, Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, 2015 July, pp. 2048–2057, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1502.03044

[29] Z. Yang, X. He, J. Gao, L. Deng, A.J. Smola, Stacked attention networks for image question answering, In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.10

[30] X. Chen, N. Mishra, M. Rohaninejad, P. Abbeel, Pixelsnail: An improved autoregressive generative model, In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018, pp. 864–872, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1712.09763

[31] A.P. Parikh, O. Täckström, D. Das, J. Uszkoreit, A decomposable attention model for natural language inference, In: Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2016, pp. 2249–2255, http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/D16-1244

[32] N. Parmar, A. Vaswani, J. Uszkoreit, Łukasz Kaiser, N. Shazeer, A. Ku, D. Tran, Image transformer, In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018, pp. 4055–4064, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.05751

[33] X. Wang, R. Girshick, A. Gupta, K. He, Non-local neural networks, In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018, pp. 7794–7803, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1711.07971

[34] J. Fu, H. Zheng, T. Mei, Look closer to see better: Recurrent attention convolutional neural network for fine-grained image recognition, In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4438–4446, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.476

[35] S. Woo, J. Park, J.Y. Lee, I.S. Kweon, CBAM: Convolutional block attention module, In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 3–19, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.06521

[36] Z. Huang, X. Wang, L. Huang, C. Huang, Y. Wei, W. Liu, W, CCNET: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation, In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 603–612, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3007032

[37] J. Fu, J. Liu, H. Tian, Y. Li, Y. Bao, Z. Fang, H. Lu, Dual attention network for scene segmentation, In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 3146–3154, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00326

[38] X.S. Wei, C.W. Xie, J. Wu, C. Shen, Mask-CNN: Localizing parts and selecting descriptors for fine-grained bird species categorization, Pattern Recognit. 76 (2018) 704–714, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2017.10.002

[39] K. He, G. Gkioxari, P. Dollár, R. Girshick, Mask R-CNN, In: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2961–2969, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1703.06870

[40] L. Ju, X. Zhao, Mask-based attention parallel network for in-the-wild facial expression recognition, In: ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2022, pp. 2410–2414, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9747717

[41] A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, G.E. Hinton, ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks, Commun. ACM 60 (2017) 84–90, https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386

[42] X.Z. Lu, W.J. Liao, W. Huang, Y.J. Xu, X. Chen, An improved linear quadratic regulator control method through convolutional neural network–based vibration identification, J. Vib. Control 27 (2020) 839–853, http://doi.org/10.1177/1077546320933756

[43] X.Z. Lu, Y.J. Xu, Y. Tian, B. Cetiner, E. Taciroglu. A deep learning approach to rapid regional post-event seismic damage assessment using time-frequency distributions of ground motions, Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 50 (2021)1612–1627, http://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3415

[44] N. Ghassemi, A. Shoeibi, M. Rouhani, Deep neural network with generative adversarial networks pre-training for brain tumor classification based on MR images, Biomed. Signal Process. Control 57 (2020) 101678, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2019.101678

[45] D. Hendrycks, K. Lee, M. Mazeika, Using pre-training can improve model robustness and uncertainty. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2019, pp. 2712–2721, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1901.09960

[46] J.M. Malof, L.M. Collins, K. Bradbury, A deep convolutional neural network, with pre-training, for solar photovoltaic array detection in aerial imagery. In 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 2017, pp. 874–877, https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS.2017.8127092

[47] P.J. Zhao, W.J. Liao, H.J. Xue, X.Z. Lu, Intelligent design method for beam and slab of shear wall structure based on deep learning, J. Build. Eng. 57 (2022) 104838, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104838

[48] T.C. Wang, M.Y. Liu, J.Y. Zhu, A. Tao, J. Kautz, B. Catanzaro, High-resolution image synthesis and semantic manipulation with conditional GANs, IEEE Conf. Comp. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (2018) 8798–8807, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00917

[49] J. Long, E. Shelhamer, T. Darrell, Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation, IEEE Conf. Comp. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (2015) 3431–3440, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298965

[50] M. Everingham, L. Van Gool, C.K. Williams, J. Winn, A. Zisserman, The pascal visual object classes (VOC) challenge, Int. J. Comput. Vis. 88 (2010) 303–338. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%252Fs11263-009-0275-4

[51] M. Everingham, S.A. Eslami, L. Van Gool, C.K. Williams, J. Winn, A. Zisserman, The pascal visual object classes challenge: a retrospective, Int. J. Comput. Vis. 111 (2015) 98–136. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%252Fs11263-014-0733-5

[52] H. Rezatofighi, N. Tsoi, J. Gwak, A. Sadeghian, I. Reid, S. Savarese, Generalized intersection over union: a metric and a loss for bounding box regression, In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019, pp. 658–666, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00075

[53] JGJ3–2010, Code for seismic design of buildings, China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, 2010 (in Chinese)

[54] GB50011–2010, Technical specification for concrete structures of tall building, China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, 2016 (in Chinese)