Abstract

Designing building structures presents various challenges, including inefficient design processes, limited data reuse, and the underutilization of previous design experience. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a powerful tool for learning and creatively using existing data to generate new design ideas. Learning from past experiences, this technique can analyze complex structural drawings, combine requirement texts, integrate mechanical and empirical knowledge, and create fresh designs. In this paper, a comprehensive review of recent research and applications of generative AI in building structural design is provided. The focus is on how data is represented, how intelligent generation algorithms are constructed, methods for evaluating designs, and the integration of generation and optimization. This review reveals the significant progress generative AI has made in building structural design, while also highlighting the key challenges and prospects. The goal is to provide a reference that can help guide the transition towards more intelligent design processes.

Keywords

Building structural design, data feature representation, generative AI algorithm, design evaluation, intelligent optimization

1. Introduction

The design of building structures is a nuanced task that necessitates the blending of empirical and mechanical knowledge. Engineers have been consistently discovering, developing, and implementing sophisticated computer-aided design technologies to streamline the process and target efficient and reliable structural designs.

In the 1980s, intelligent design methods were proposed based on expert system algorithms (Maher, 1987). In the following years, a series of intelligent design methods based on biologically inspired algorithms emerged together with the concept of generative design (Fischer & Herr, 2001; Kicinger et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2021). Advancements in computer technology drove the digitization and automation of building structural designs forward at an unprecedented pace. However, expert system algorithms and biologically inspired algorithms find themselves grappling with issues in data learning, design rule encoding, and design efficiency, which hamper their wider application.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, notably deep learning, have made remarkable progress in learning from existing data and generating new designs, which sets them apart from conventional expert systems and biologically inspired algorithms. Generative AI design, which harnesses machine learning algorithms to learn from data and unfolds new content, has been identified as one of the top ten technology trends for 2023 (DAMO Academy, 2023). Intelligent generative technologies, such as DALL-E (Ramesh et al., 2021) and ChatGPT by OpenAI and AlphaFold by DeepMind (Jumper et al., 2021), have demonstrated the versatility of generative AI in various fields and have become a cutting-edge area of research.

Building structural designs rely primarily on drawings that translate into structured or image data. Engineers complete the design process based on an architectural design with multiple constraints such as compliance and economy. The end-to-end design process of generative AI is consistent with that of building structural design by engineers (Liao et al., 2021), equipped with powerful learning and generating capabilities to tackle the intricate puzzles of intelligent design. Therefore, it has become a new research topic.

In the realm of design and analysis, several notable review studies have been conducted. Aldwaik and Adeli (2014) conducted a review focusing on the optimization of high-rise building structures, utilizing nature-based optimization approaches like the neural dynamics model and genetic algorithms. Chi et al. (2015) and Omrany et al. (2023) explored the integration of building information modeling (BIM) with smart technologies in structural design practice, such as structural design, planning, analysis, and optimization. Afzal et al. (2020) provided an overview of structural components, optimization strategies, and the utilization of various computational tools in RC structural design optimization. Pizarro et al. (2022) reviewed rule- and learning-based methods for intelligent recognition and design in architecture. Sun et al. (2022) delved into the research on machine learning applications in building structure design and performance evaluation. Zakian and Kaveh (2023) presented an overview of seismic design optimization, encompassing common solution methods, optimization problem types, and optimization goals. Y¨¹ksel et al. (2023) analyzed the research status of genetic algorithms, fuzzy logic, and machine learning methods in engineering structure design, covering areas such as design generation, evaluation, optimization, decision-making, and modeling. Wang et al. (2023) conducted a review specifically on the application of AI technology in material and structural analyses within the field of civil engineering. Topuz and Çakici Alp (2023) evaluated the current state of machine learning in computer-aided design, engineering, and manufacturing of architecture. Lastly, Ko et al. (2023) introduced advancements in automated spatial layout planning combined with AI.

Several review studies also explored AI applications in the realm of construction and maintenance. Amezquita-Sanchez et al. (2016), and Li and Adeli (2018) provided an insightful review and outlook on the utilization of machine learning technologies in structural system identification, health monitoring, vibration control, design, and optimization. Baduge et al. (2022) introduced the latest advancements in applying AI technologies, including machine learning and deep learning, in building design and visualization within the context of the building industry 4.0. Wu et al. (2022) presented a comprehensive state-of-the-art review on the utilization of GANs to tackle challenging tasks in the built environment. Saka et al. (2023) assessed the potential of GPT models in the construction industry, identifying opportunities for their implementation throughout the project lifecycle. Jia et al. (2023) explored diverse approaches for constructing graph data from common construction data types and highlighted the significant potential of GNNs for the construction industry.

Table 1 Scopes of existing review studies related to AI-assistant building structural design

|

Dsgn. |

Anlys. |

C&O&M |

DL (inc. Gen. AI) |

ML |

Optim. |

DRL |

|

|

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||||

|

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||||

|

Amezquita-Sanchez et al. (2016) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||

|

Li and Adeli (2018) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||||

|

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||||

|

Sun et al. (2022) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||

|

Pizarro et al. (2022) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||||

|

Baduge et al. (2022) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||

|

Wu et al. (2022) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||

|

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||||||

|

Y¨¹ksel et al. (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||

|

Wang et al. (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||||

|

Omrany et al. (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||

|

Saka et al. (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

|||

|

Jia et al. (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||||

|

Topuz & Çakici Alp (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||

|

Ko et al. (2023) |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

||||

|

Ours |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

¡Ì |

Dsgn. = Design, Anlys. = Analysis, C&O&M = Construction & Operations & Maintenance, DL = Deep Learning, Gen. AI = Generative AI, ML = Machine Learning, Optim. = Optimization, and DRL = Deep Reinforcement Learning.

However, there is a noticeable gap in the analysis and discussion surrounding the development and application of generative AI in the structural design of buildings. This gap results in a lack of systematic and targeted research within this field. Upon reviewing existing studies, it becomes evident that the research findings in this area are fragmented and incomplete. Researchers encounter challenges in addressing specific issues, while the entry barriers for new researchers entering this field are on the rise. These factors collectively impede further progress and hinder the advancement of generative AI in building structural design. Therefore, this study aims to provide an overview of existing intelligent structural design methods and focuses on the achievements and applications of generative AI in building structural design, which has undergone rapid development over the past three years. The analysis of existing studies reveals that the primary research areas in generative AI-based structural design encompass data representation, generation algorithms, evaluation methods, and the integration of AI generation with design optimization. By conducting investigations in these pertinent domains, the advancement of AI-based building structural design technology can be effectively facilitated. Accordingly, this study will predominantly center around showcasing the accomplishments of existing research within these specific areas.

Section 2 provides a macro-introduction to current AI methods and their applications in building structural design. Sections 3¨C5 review the data feature representation, generative algorithm construction, and evaluation methods in generative AI. Section 6 introduces methods coupling intelligent generation and optimization, and Section 7 presents typical engineering application cases of intelligent building structure design. Section 8 provides relevant conclusions and prospects for the future development of this research field.

Consequently, this study highlights the potential of generative AI in building structural design and the need for further research in this field. The development and application of generative AI in structural design can significantly enhance the efficiency and accuracy of the design process, leading to more sustainable and safer building structures.

2. Introduction to artificial intelligence (AI) methods and applications in building structural design

2.1 AI Methods

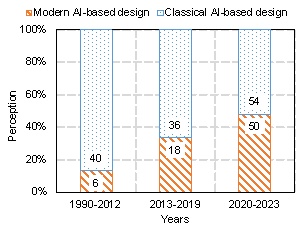

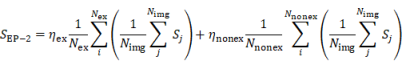

Research on AI methods has been conducted for a considerable period. In this study, the timeline was partitioned using 2012 as a reference point, which marks the "deep learning era" owing to the highly effective image classification algorithm AlexNet (Krizhevsky et al., 2012). According to Y¨¹ksel et al. (2023), as illustrated in Figure 1, most AI methods before 2012 were categorized as classical AI methods, whereas those after 2012 were referred to as modern AI methods. This review focuses primarily on deep-learning algorithms developed after 2012.

(1) Classical AI methods:

Representative methods include knowledge-based systems and biologically inspired algorithms. Knowledge-based systems include expert systems (Sriram et al., 1985), fuzzy logic (Mendel, 1995), and generative design grammars (Chakrabarti et al., 2011). Biologically inspired algorithms include genetic algorithms (Adeli & Kumar, 1995), particle swarm optimization (Perez & Behdinan, 2007), and cellular automata (Kita & Toyoda, 2000).

(2) Modern AI methods:

Since 2012, the AI field has undergone a comprehensive development driven by deep learning, which can handle big data, extract high-dimensional features, and significantly improve learning from data (LeCun et al., 2015). Typical deep learning methods include deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (Krizhevsky et al., 2012; LeCun et al., 2015), deep graph neural networks (GNNs) (Kipf & Welling, 2016), and deep recurrent neural network/long short-term memory (RNN/LSTM) (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997; Chung et al., 2014). In addition, advanced deep learning algorithms have been developed using these methods, such as the variational autoencoder (VAE) (Kingma & Welling, 2013), generative adversarial network (GAN) (Goodfellow et al., 2020), transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017), and diffusion models (Croitoru et al., 2023). In recent years, generative AI (Goodfellow et al., 2020; Vaswani et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2020; Croitoru et al., 2023) has become a representative technological advancement in deep learning research. The emergence of generative AI or deep generative methods has opened new possibilities for intelligent design.

Presently, modern AI methods have found extensive applications in various engineering fields, including architecture, mechanical engineering, and aerospace engineering (Y¨¹ksel et al., 2023). They have proven to be effective in generating architectural layouts, rendering architectural images (Huang & Zheng, 2018; Chaillou, 2019; Nauata et al., 2020, 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Aalaei et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023; Jia et al., 2023), generating wheel structures (Oh et al., 2019), and aerodynamic shapes of aircraft (Shu et al., 2020). These advancements have provided engineers with enhanced initial design solutions, elevating both design efficiency and quality. The insights from these related studies serve as crucial references for the development of generative AI-based intelligent design in building structures.

Figure 1 Artificial intelligence (AI) methods widely adopted in building structural design

2.2 Application of AI in building structural design

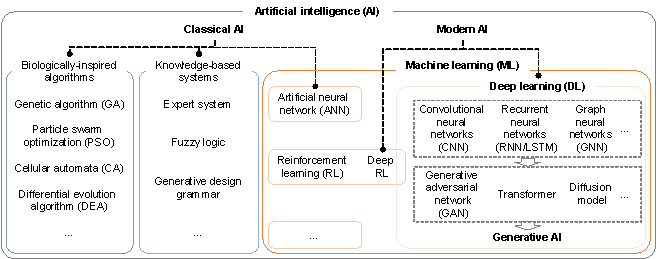

The building structural design process can be divided into three primary stages: conceptual design (scheme design), detailed design (preliminary or optimization design), and construction drawing design. Among these stages, the conceptual design stage significantly impacts the final design outcome and relies heavily on design experience and knowledge (as shown in Figure 2). Therefore, in the conceptual design stage, AI plays a significant role in the structural design of buildings.

Figure 2 Influence of the building structural design phase on project cost (Paulson, 1976)

The core task of a conceptual building structural design is design generation (also known as synthesis). According to Maher (1987), building structural design synthesis methods mainly refer to the generation of corresponding designs guided by specific knowledge fragments, such as heuristic rules and descriptive frameworks. In addition, with the development and application of generative AI technologies that can learn data features and generate new designs, current structural design synthesis methods mainly include heuristic search-based, descriptive growth-based, and generative AI learning-based designs (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of three mainstream intelligent design modes

|

Heuristic search-based |

Descriptive growth-based |

Generative AI learning-based |

|

|

Concept description |

Utilizing the provided initial solution within predetermined boundary constraints, the iterative process aims to systematically search for the optimal result. |

The process involves establishing generation rules and constraints, commencing from the initial design, and subsequently iteratively optimizing it based on the descriptive generation rules. |

By leveraging existing data, AI comprehends the mapping patterns between building and structure. Trained AI generates a corresponding structural design for a new building design in a single comprehensive step. |

|

Concept illustration |

|

|

|

|

Representative methods |

Required |

Partial required |

Not required |

|

Initial structural design |

Required |

Required |

Not required |

|

Manually defined rules |

Required |

Required |

Not required |

|

Iteration design |

Not required |

Not required |

Required |

|

Learning |

High |

Relatively high |

Medium |

|

Performance |

Relatively low |

Medium |

High |

|

Efficiency |

Required |

Partial required |

Not required |

Heuristic search-based designs primarily use biologically inspired computation techniques, such as genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, and cellular automata (Kicinger et al., 2005; Hofmeyer & Delgado, 2015; Zhang & Mueller, 2017; Kanyilmaz et al., 2022; Nimtawat & Nanakorn, 2009; Nimtawat & Nanakorn, 2010, 2011; Shahrouzi & Pashaei, 2013; Reisinger et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Boonstra et al., 2021; He et al., 2022; Shea et al., 2005; Krish, 2011; Tafraout et al., 2019). Descriptive growth-based designs primarily use generative design grammar (Shea & Cagan, 1999; Chakrabarti et al., 2011; Königseder & Shea, 2014; Zhao & Luo, 2019; Boonstra et al., 2020; Cascone et al., 2021). These intelligent design methods have been widely applied in multiple areas of building structural design, such as multi-scheme search, comparative selection, and material optimization, and have promoted the progress of digitalization and automation in structural design. However, these classical methods face difficulties regarding data learning and design efficiency. In contrast, generative learning is an intelligent design method dominated by generative AI, which has powerful design data learning and efficient new design generation capabilities and has been continuously developing and advancing in recent years.

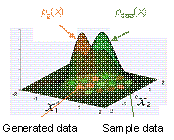

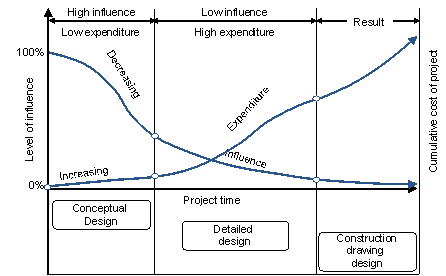

The main architecture of the generative AI algorithms is shown in Figure 3, which includes a dataset, a neural network model, and a loss function module. The development and application of generative AI in building structural design will mainly focus on these three parts, and a detailed analysis and summary are presented in Sections 3¨C5.

Figure 3 Algorithm framework of generative AI

To further understand the current state of research on intelligent structural design, we conducted a search of the Web of Science Core Collection for relevant papers. First, a search was conducted on AI-based structural design methods, yielding 188 search results. Subsequently, searches were conducted on classical AI-based and modern AI-based structural design methods, resulting in 130 and 74 search results, respectively. The search formulae are listed in Table 3.

Table 3 Search objects and formulas used in the Web of Science core collection and the resulting number (accessed on April 20, 2023)

|

Search objects |

Search formulas |

Number of studies |

|

Classical AI-based building structural design |

(TS=("building" OR "architecture*") AND TS=("structur* design") AND TS=("intelligen*" OR "automat*" OR "artificial intelligence" OR "design intelligence" OR "generative" OR "optimiz*" OR "explorat*") AND TS=("expert system*" OR "fuzzy logic" OR "genetic algorithm" OR "generative grammar" OR "evolution" OR "particle swarm optimization" OR "cellular automata")) |

130 |

|

Modern AI-based building structural design |

(TS=("building" OR "architecture*") AND TS=("structur* design") AND TS=("intelligen*" OR "automat*" OR "artificial intelligence" OR "design intelligence" OR "generative" OR "optimiz*" OR "explorat*") AND TS=("machine learning" OR "deep learning" OR "neural network" OR "generative adversarial network" OR "variational autoencoder" OR "transformer" OR "diffusion model")) |

74 |

|

AI-based building structural design |

The sum of these two formulas |

188 |

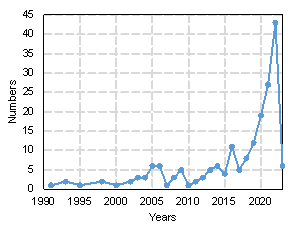

Figure 4(a) shows the change in the number of research papers on AI-based building structural designs, indicating a continuous increase in intelligent design research over the years, with a significant increase since 2020. By comparing the classical and modern AI methods, as shown in Figure 4(b), it can be observed that classical AI was the mainstream research method for intelligent design before 2012. Since 2012, modern AI has rapidly developed, and the related research papers have increased threefold; however, some differences still exist compared to classical AI methods. Since 2020, generative AI technology has significantly improved its capabilities and has been developing in-depth in the field of structural design, with research papers on par with classical AI methods and accounting for 48% of the total research, showing a trend of surpassing classical AI methods.

|

(a) Development history of intelligent design of building structures |

(b) Comparison between classic AI-based and modern AI-based intelligent designs |

Figure 4 Development history of intelligent design of building structures

In summary, by analyzing the recent trends in intelligent building structural design, AI-based methods using deep learning have gradually become the primary research focus. These methods are referred to by different names, including intelligent generative design, deep generative design, intelligent design, and deep-learning-based design. However, the core technology of these methods primarily involves learning from existing design data, empirical knowledge, and physical principles to master the ability to generate new designs intelligently. As this is consistent with the essence of generative AI, this study collectively refers to these methods as generative AI-based intelligent designs for building structures.

3. Data feature representation and dataset construction

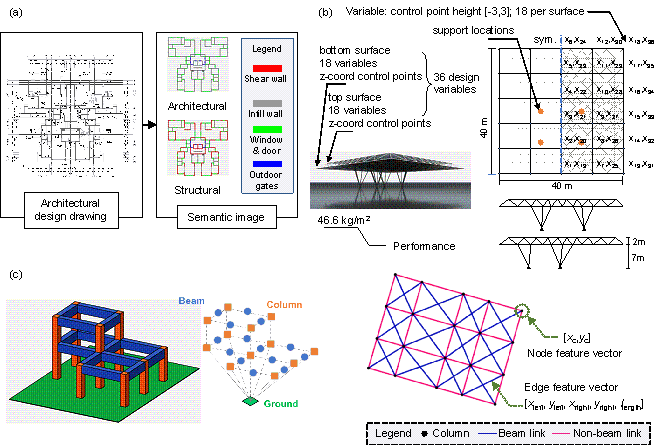

The representation of the data features is crucial in building structural intelligent design. This representation is related to the geometric and mechanical characteristics of the structural design and is subject to the limitations of deep-learning algorithms. In building structural design, data features mainly include topological, pattern, and size features. Topological features refer to the layout of structural components in space and the connection relationship between components to effectively resist overall lateral and vertical loads. Pattern features refer to the local geometric configuration of components that must be in special patterns (such as L-shaped, T-shaped, and C-shaped) to resist the load of the local component. Size features refer to the cross-sectional sizes of structural components.

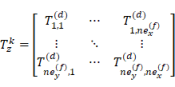

Generative AI algorithms utilize convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to process data as tensors (including 1-dimensional vectors, 3-dimensional images, and n-dimensional matrices). In contrast, graph neural networks (GNNs) are suitable for processing data in graphs (node and edge representations, with 1-dimensional vector features embedded in nodes and edges). Tensor data can better express patterns and size features in the design, whereas graphs are more conducive to expressing topological features.

Therefore, generative AI algorithms can effectively extract features and learn by appropriately representing the data features in building structural design. This section reviews the data feature representation methods and dataset construction used in existing research.

3.1 Data feature representation

Table 4 summarizes the tensor-based and graph-based data representation methods used in related research, and Figure 5 illustrates the typical representation methods. Tensor-based data representation is more commonly used in current research, whereas graph-based representations are less common. Tensor representation is more intuitive and straightforward, and thus it is more widely used in current generative AI-based intelligent design methods. Although graphs are better suited for expressing topological features, they require complex and sophisticated designs to represent pattern and size features.

(1) Tensor-based representation

Table 4-1 Tensor-based representation for data features

|

Research |

Input features |

Output features |

|

Liao et al. (2021,

2022) Lu et al. (2022) |

Image of architectural components layout, Matrix of design conditions |

Image of shear wall components layout |

|

Liao et al. (2023) |

Image of shear wall components layout, Matrix of isolation bearing layout locations |

Matrix of isolator parameters |

|

Zhao et al. (2022) |

Image of shear wall components layout, Image of architectural space |

Image of beam components layout |

|

Fei et al. (2022b) |

Image of frame-core tube components layout, Matrix of design conditions |

Matrix of cross-sectional size of frame-core tube components |

|

Pizarro et al. |

Image of architectural components layout, Vector data of design conditions and structure-related parameters |

Two-element vector, representing thickness and length of shear wall component |

|

Fu et al. (2023) |

Stage 1: Image of architectural components layout, Stage 2: Image of architectural and column components layout |

Stage 1: Image of column components layout, Stage 2: Image of brace components layout |

|

Ampanavos et al. |

128¡Á128¡Á4 tensor of architectural layout, previously arranged columns, pixel coordinate x value, and pixel coordinates y values |

Output 1: Predicted coordinates of the four columns Output 2: One-hot encoding of the predicted three column types (free-standing, column on corner, or column on wall) |

|

Danhaive et al. (2021) |

Design vector (the initial coordinates of nodes controlling the spatial structure shape) |

Reconstructed design vector (the designed coordinates of nodes controlling the spatial structure shape) |

|

Rodriguez et al. (2020) |

3D design connectivity map (The 3D space is divided into grids, and each node has 13 potential connections with surrounding nodes; the input vector dim is 21¡Á21¡Á21¡Á13) |

3D design connectivity map (the output vector dim is 21¡Á21¡Á21¡Á13, different values indicate different node connections scenario and the corresponding structural design) |

|

Mirra & Pugnale (2021) |

Five-element input vector, n: number of openings; ¦Á: degrees opening rotation; d: opening position; w: opening width; c: curvature of the support edges |

Five-element output vector, different parameters correspond to different structural design |

|

Kallioras & Lagaros |

|

Final density value for each finite element of the initial domain |

|

Huang et al. (2022) |

Density values of m fine-solution elements in a coarse-resolution element |

Nodal values of independent extended multi-scale finite element method (EMsFEM) shape functions |

Figure 5 Tensor-based and graph-based representation of data features. (a) Image-based representation (Liao et al., 2021). (b) Vector-based representation (Danhaive et al., 2021). (c) Graph-based representation (Chang & Cheng, 2020; Zhao et al., 2023b)

(2) Graph-based representation

Table 4-2 Graph-based representation of data features

|

Research |

Input features |

Output features |

|

Zhao et al. (2023b) |

Nodes: frame columns (featured as coordinates) Edges: potential beams (features coded for non-beams) |

Nodes: frame columns Edges: beams (features as 1) and non-beams (features as 0) |

|

Zhao et al. (2023c; 2023d) |

Representation 1: bidirectional graph Nodes: architectural component endpoints (features as coordinates) Edge: architectural component (features as one-hot component type and endpoint coordinates) |

Nodes: component endpoints (featured as coordinates) Edge: shear wall component (features as component length) |

|

Representation 2: one-way graph Nodes: architectural component (features as one-hot component type and node coordinates) Edge: architectural component (features as one-hot component type and endpoint coordinates) |

Nodes: shear wall component (features as coordinates) Edge: node connection relationship (features as endpoint coordinates) |

|

|

Chang & Cheng (2020) |

Node: structural component (features as [p1; p2; B; T; L], p1 and p2 are member endpoints, B is the component type, T is the one-hot code of the section size, and L is the floor number) Edge: the connection relationship of components |

Node: structural component (features as the one-hot code of the section size) |

|

Hayashi & Ohsaki |

Nodes: truss endpoints (features represent boundary conditions) Edges: potential truss components (features include existence, geometric properties, stress state) |

Edge: connectivity of the truss endpoints, that is, the existence or absence of truss components |

|

Zhang et al. (2023) |

Stage 1: architectural image Stage 2: nodes represent the column and shear wall endpoints |

Stage 1: endpoints of the column and shear wall Stage 2: edges represent the beam and shear wall |

3.2 Dataset construction

After determining the data feature representation method, the collected data were processed to construct the dataset. Table 5 provides detailed information on the datasets described in the current literature, including the design object, data content, data quantity, and whether they are open source. Currently, the construction of datasets in building structural intelligent design is relatively scarce, and the introduction of datasets is not sufficiently comprehensive. One significant reason is the limited availability of publicly accessible field data.

Table 5 Dataset construction

|

Research |

Design object |

Data content |

Data quantity |

Open access |

|

Liao et al. (2021) |

Shear wall structure |

Image of architectural and structural components and two design conditions |

193 building projects |

Yes |

|

Pizarro et al. |

Shear wall structure |

Image of architectural components and 30 design feature vectors |

165 building projects |

No |

|

Fu et al. (2023) |

Steel frame-brace structure |

Image of architectural components, frame columns, brace layout |

110 building projects |

No |

|

Frame structure |

Graph of layout parameters of the frame beam |

4 fundamental shapes, and 20000 layout designs generated by parametric design |

No |

|

|

Zhao et al. |

Shear wall structure |

Graph of architectural and structural components layout |

324 building projects |

No |

|

Mirra & Pugnale |

Shell structure |

Structured data: parameters of structural components |

1 fundamental shape, and 800 designs generated by parametric design |

No |

|

Rodriguez et al. |

3D structure |

Structured data: parameters of structural components |

2 fundamental shapes, and 6000 and 9000 designs generated by parametric design |

No |

Data augmentation methods are widely used to address the issue of limited data. (1) Image data augmentation methods, such as flipping, symmetry, and translation of images, can effectively increase the data up to four times the original data without changing the attributes of the structural design (Liao et al., 2021; Fu et al., 2023). Augmenting data through overall image segmentation can increase the data by hundreds of times by partitioning the completed design image into several local design images without changing the building and structural size (Pizarro et al., 2021a; Zhao et al., 2022). (2) Tensor data augmentation can generate hundreds or thousands of data by parametric design for structural topology and component size (Zhao et al., 2023b; Mirra & Pugnale, 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2020). (3) Graph data augmentation can also be performed based on the spatial relative coordinate position in each node of the graph, where data can be augmented more than 3000 times by overall translation, flipping, and rotating coordinates (Zhao et al., 2023c, 2023d).

3.3 Summary of data feature representation

Currently, there exist significant variations in the extraction and representation of data features for different building structure forms. Whether it involves pixel image representation, graph representation, or vector representation, it is crucial to employ suitable encoding methods that effectively capture the topological, geometric, spatial, and other pertinent information of building structure design. When coupled with corresponding generative AI algorithms, these encoding methods can facilitate the generation of structural designs. However, it is important to acknowledge that each representation method possesses its own limitations and cannot comprehensively capture all design features. Therefore, it becomes imperative to address the following aspects:

(1) Achieve a fusion representation of multi-modal data features, enabling the simultaneous learning of information related to topology, geometry, space, and design conditions. This approach will enhance the comprehensive understanding and representation of building structure designs.

(2) Propose a general representation technique that can effectively densify different types of building structure design features, thereby addressing the issue of sparsity associated with architectural design information. This technique will allow for a more complete representation of diverse design components.

(3) Lastly, the rapid advancement of intelligent design in this field heavily relies on the accumulation and support of open-source data. Therefore, there is a need for increased sharing of open-source data within the architectural community to facilitate further progress and innovation.

4. Generative AI algorithms for structural design

The design methods and rules for the different types of building structures vary significantly. Therefore, the corresponding generative AI algorithms shall be developed to address the design of structures with different features. Generative AI effectively masters the rules for the intelligent generation of building structures by learning from existing design data, mechanical mechanisms, and empirical rules. This section focuses on introducing generative AI algorithms, specifically for conventional residential building structures, complex spatial building structures, and continuous topology structure designs.

4.1 Residential building structures

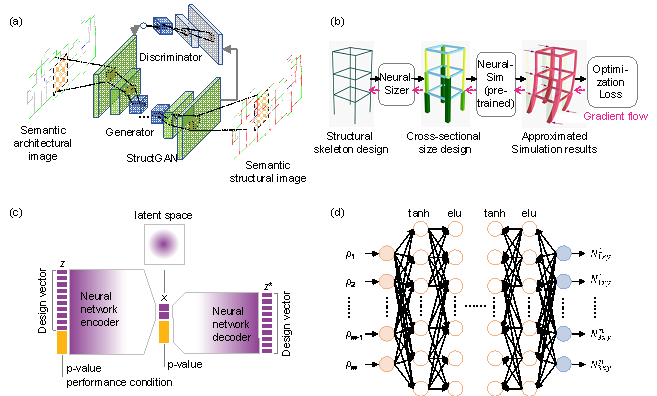

Generative AI is primarily used for designing residential building structures such as shear walls, frames, and frame-brace structures. CNNs and GNNs are the primary generative AI technologies used. Researchers have further improved the network architecture by incorporating GANs and GNNs to learn mechanical mechanisms and empirical rules. Attention and LSTM technologies have also been used in the design-generation process. A detailed analysis of these techniques is presented in Table 6.

Table 6-1 Generative AI algorithms for residential building structural design

|

Research |

Generative AI algorithm |

Structural system |

||||||||||

|

Liao et al. (2021) Zhao et al. (2022) Zhao et al. Fei et al. (2022a) Liao et al. (2022) |

The generative adversarial network (GAN) consists of a generator and a discriminator. The generator comprises an encoder comprising convolutional networks and a decoder consisting of deconvolutional networks. The discriminator is a multi-scale discriminator constructed using convolutional networks. Zhao et al. (2023a) added a self-attention module to the generator network. Liao et al. (2022) improved the encoder of the generator by using a fusion network that combines text features and image features. |

Shear wall components Beam components |

||||||||||

|

Lu et al. (2022) |

GAN with mechanical evaluator enhancement. The mechanical evaluator is a ResNet-based performance evaluation surrogate model for mechanical properties. |

Shear wall components |

||||||||||

|

Fei et al. (2022b) |

GAN with knowledge evaluator enhancement. The knowledge evaluator is a tensor operator encoding empirical rules into a differentiable loss function. |

Frame-core tube structure |

||||||||||

|

Liao et al. (2023) |

GAN with the mechanical evaluator and rule evaluator enhancement. The mechanical evaluator and rule evaluator are a ResNet-based surrogate model and differentiable tensor operator. |

Seismic isolator of shear wall structure |

||||||||||

|

Pizarro et al. (2021a & 2021b) |

Generator and discriminator. Pizarro et al. (2021a) only adopt the generator, Pizarro et al. (2021b) use a GAN. |

Shear wall components |

||||||||||

|

Fu et al. (2023) |

Two GANs are used for a two-stage design process. The first stage involved column layout design, while the second involved brace layout design. |

Steel frame-brace structure |

||||||||||

|

Ampanavos et al. (2021) |

Generative network: A CNN and LSTM-based generative network. The design process does not generate the entire design end-to-end in one go. Instead, it generates only four columns simultaneously based on the architectural plan and the previous column layout design. The process is repeated iteratively to complete the structural design. |

Column components of frame structure |

||||||||||

|

Zhao et al. (2023b; 2023c; 2023d) |

Graph generative network: a GNN that embeds edge features is used, which can simultaneously learn node and edge features.

|

Beam components of frame structure and shear wall components |

||||||||||

|

Chang & Cheng (2020) |

Graph generative network: The network consists of an encoder, feed-forward propagation, and a decoder. The encoder maps the input node features to the embedding space. Feed-forward propagation iteratively updates each node's embedded features. The decoder consists of a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). |

The cross-sectional size of frame structure |

Note: The GAN is shown in Figure 6(a), and the physics-enhanced GNN is shown in Figure 6(b).

4.2 Spatial structures

Spatial structures often have a high degree of freedom and complexity in their shape; therefore, generative AI mainly uses VAE algorithms for intelligent design. The design-generation results can be effectively changed by operating the latent space in the VAE network, thereby providing a reference for exploring more structural design schemes.

Table 6-2 Generative AI algorithms for spatial structure design

|

Research |

Generative AI algorithm |

Structural system |

|

Rodriguez et al. (2020) Mirra & Pugnale (2021) |

Variational autoencoder (VAE) generator network consisting of an encoder, latent space, and decoder. The encoder and decoder are both artificial neural network (ANN) models, and the latent space is a feature reduction space obtained by extracting the input features through the encoder. Multiple structural design schemes can be generated by randomly sampling the dimension-reduced features in the latent space. |

3D spatial structures, Spatial shell structures |

|

Danhaive et al. (2021) |

Based on the conventional VAE, adjustments to the decoder-generated design can be made by controlling the latent space features through performance conditions. |

Spatial shell structures |

Note: The VAE is shown in Figure 6(c)

4.3 Continuous structures

Generative AI is less commonly used in the topological design of continuous building structures. Currently, it is mainly used to design the topology of beam components, with algorithms primarily based on ANN and CNN methods. The structural topology is primarily generated by inputting the geometric configurations.

Table 6-3 Generative AI algorithms for continuous structures design

|

Research |

Generative AI algorithm |

Structural system |

|

Kallioras & Lagaros (2020) |

Deep belief networks to predict the parameters of structures |

Beam topology |

|

Huang et al. (2022) |

ANN |

Structural topology |

Note: The ANN is shown in Figure 6(d)

Figure 6 Typical generative AI methods

for building structural design. (a) GAN (Liao et al., 2021),

(b) GNN (Chang & Cheng, 2020), (c) VAE (Danhaive et al., 2021), (d) ANN

(Huang et al., 2022)

4.4 Summary of generative AI algorithm

A diverse range of generative AI algorithms exists, with GANs, GNNs, and VAEs being the most commonly utilized techniques. These algorithms have demonstrated their efficacy in designing various types of structures, including shear walls, frames, and frame-brace structures. However, despite their widespread application, there is still considerable progress to be made before these technologies reach a level of maturity and are extensively embraced in engineering practice. Moving forward, numerous challenges need to be addressed in the realm of intelligent generation:

(1) Presently, the generated structural designs by AI tend to be rough, making it difficult to ensure the rationality of local design details. For instance, components like columns and shear wall elements generated by GANs may exhibit omissions in certain spatial areas, seriously degrading the mechanical performance of building structures. The primary reason behind this issue lies in GANs relying on learned high-dimensional probability distributions instead of rule-based deterministic design. Consequently, important pixel details can be missed during the generation process.

(2) Generative AI has limited learning capabilities when it comes to various constraints in building structural design rules and mechanical requirements. Although the current algorithms learn constraints such as symmetry and inter-story drift drifts, they struggle to meet more complex rule requirements and mechanical performance constraints (Pizarro et al., 2023).

(3) The application of more powerful generative AI technologies, such as large language models (LLMs) and diffusion models, is limited in intelligent architectural structural design due to their relatively short development time and high hardware requirements. The diffusion model is presently widely used in image synthesis domains (Cao et al., 2022; Ramesh et al., 2022; Saharia et al., 2022; Rombach et al., 2022) and is expected to be gradually explored in building structural design to enhance the effectiveness of intelligent design. Typically, diffusion models offer superior image generation quality compared to techniques like GANs and VAEs. Some studies have already been conducted in building facade design using diffusion models (Chen et al., 2023). On the other hand, LLMs find extensive application in text sequence generation (Zhao W.X. et al., 2023; Saka et al., 2023). However, a key challenge with LLMs is representing building structural design features as the 1-dimensional sequence data widely used by LLMs. Once the challenge of data representation is overcome, it is expected that more research will be conducted in this area.

(4) Currently, there is a scarcity of open-source algorithms for AI-based building structural design, highlighting the need for further open communication in the field. Some widely used open-source code packages in AI design for building structures include U-net (Ronneberger et al., 2015), pix2pix (Isola et al., 2017), pix2pixHD (Wang et al., 2018), and graph-sage (Hamilton et al., 2017).

In the future, generative AI technologies in the field of building structural design need to become more accurate and adhere to empirical rules to ensure their effectiveness and practicality.

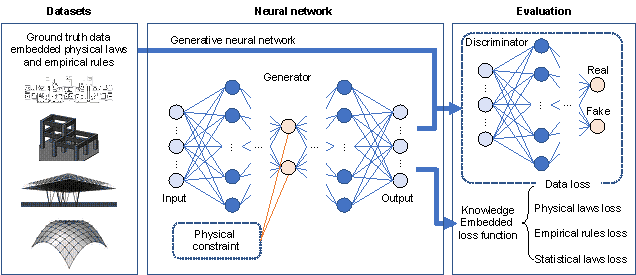

5. Evaluation methods for generative AI design

After the intelligent design of building structures is completed, it is essential to assess the quality of the design results to guide the optimization of the generative algorithm more effectively and improve the subsequent design quality. Relevant methods include evaluation during the generative AI training and testing phases. The training phase evaluation involves constructing a loss function that must ensure that it is differentiable and can be embedded in the computational graph of the neural network to guide the learning and optimization of generative AI effectively. However, the testing phase evaluation has no such restrictions, and the feasibility of the design results is measured during this phase.

5.1 Construction of loss function

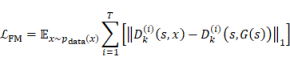

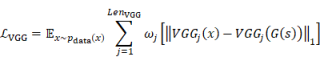

Generative AI losses mainly include data, mechanical, and empirical rule losses. Data loss mainly refers to the difference between the generated and target designs, and common data difference measurement methods such as cross-entropy or mean square error (MSE) can be used to calculate it. Mechanical and empirical rule losses must be constructed based on specific features, and the challenge is to ensure that the error of the loss function can be backpropagated in a neural network computation. The mechanical loss is typically evaluated using a neural network as a surrogate model for the mechanical performance of the design structure, and this surrogate model must be pre-trained. Constructing an empirical rule loss function is challenging, and its core is the construction of differentiable functions based on specific empirical rules. Owing to the significant differences between various empirical rules, it is difficult to form a unified construction paradigm. The empirical rule loss function primarily considers symmetry, the uniformity of cross-sectional dimensions, and other rules. The details of the loss function construction methods used in relevant research can be found in Table 7-1.

Table 7-1 Loss function (data loss, mechanical loss, empirical loss)

|

Research |

Loss function |

Structural system |

|

Liao et al. (2021, 2022) Lu et al. (2022) Fei et al. (2022a) Zhao et al. (2022, 2023a) Fu et al. (2023) |

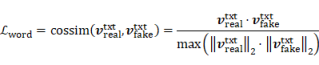

Image loss of discriminator: Image loss of generator: x is label, s is input, z is generated data, D( ) is the discriminative network, G( ) is the generative network, VGG( ) is the VGG19 network |

Shear wall structure; Beam structural components |

|

Liao et al. (2022) |

Text loss of generator: |

Shear wall structure |

|

Lu et al. (2022) |

Mechanical loss of generator: |

Shear wall structure |

|

Fei et al. (2022b) |

|

Frame-core tube structure |

|

Pizarro et al. (2021a & 2021b) |

|

Shear wall structure |

|

Ampanavos et al. (2021) |

The loss function was defined as the weighted sum of the mean absolute error of the coordinates output layer and the categorical cross-entropy of the column type output layer, with weights 1.0 and 0.2. |

Frame structure |

|

Zhao et al. (2023b) |

|

Frame structure |

|

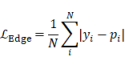

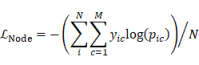

Zhao et al. (2023c) |

where N is the edge (node) sample number; yi is the target value of the i-th sample; pi is the predicted value of the i-th sample. |

Shear wall structure |

|

Chang & Cheng (2020) |

Mechanical loss: |

Frame structure |

|

Danhaive et al. (2021) |

|

Spatial shell structures |

|

Rodriguez et al. (2020) |

|

3D spatial structure |

|

Mirra & Pugnale (2021) |

|

3D spatial structure |

|

Huang et al. (2022) |

The loss function contains

two parts: one is the MSE between the prediction ( |

Structural topology |

5.2 Evaluation methods for structural design results

The evaluation of the design results mainly focuses on design similarity, mechanical compliance, material consumption, and engineer experience-based judgment to achieve a more reasonable and accurate design result evaluation. Evaluating design similarity involves comparing the consistency between the AI and engineer designs without involving mechanical performance calculations. Therefore, its evaluation efficiency is high, and it is suitable for evaluating a large number of design test results, primarily for comprehensively evaluating AI capabilities. Mechanical compliance and material consumption analyses rely on mechanical analysis, which consumes more time but yields accurate results. This method is suitable for evaluating only a small number of design results. Engineer experience evaluation takes the longest time, requires reasonable design and evaluation survey forms, invites multiple engineers for analysis, and has a higher requirement for engineering quality. Therefore, the proposed method is suitable for engineering applications. Details of the relevant evaluation methods are listed in Table 7-2.

Table 7-2 Evaluation methods for design results

|

Research |

Evaluation method |

Indicator |

Structural system |

|

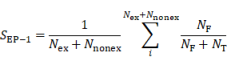

Liao et al. (2021, 2022) Lu et al. (2022) Zhao et al. (2022, 2023a) Fei et al. (2022a) Pizarro et al. (2021a & 2021b) Zhao et al. (2023c) |

Data similarity analysis,

|

|

Shear wall structure; Beam structural components |

|

Mechanical compliance |

Structural natural frequency, inter-story drift ratio, axial compression ratio, etc. |

||

|

Economic feasibility |

Concrete and steel material consumption |

||

|

Fei et al. (2022a) |

Proportion of cantilevered floor |

|

Shear wall structure |

|

Liao et al. (2021) |

Engineer evaluation: Real or fake judgement, Design rationality |

|

Shear wall structure |

|

Fu et al. (2023) |

Differences of material consumption |

Difference between column and brace, respectively |

Frame-braced structure |

|

Engineer grading: Rationality of key nodes |

Arrangement on key nodes Reasonability of overall layout |

||

|

Ampanavos et al. (2021) |

Evaluation of the accuracy of column layout |

Accuracy |

Frame structure |

|

Zhao et al. (2023b) |

Evaluation of the accuracy of beam layout |

Accuracy, F1 score |

Frame structure |

|

Chang & Cheng (2020) |

Accuracy of column cross-sectional size; inter-story drift ratio |

Accuracy, code limitation of inter-story drift ratio |

Frame structure |

|

Danhaive et al. (2021) |

Material consumption |

Structural mass |

Spatial shell structures |

|

Mirra & Pugnale (2021) |

(1) Low variance, that is, the presence of several samples that are similar to each other; and (2) Consistency, that is, the recurrence of some underlying features in all the samples. |

No specific indicators, engineers select them |

3D Spatial shell structures |

|

Huang et al. (2022) |

(1) Optimized structural compliances (2) Efficiency |

Computational methods for topology optimization |

Structural topology |

5.3 Summary of evaluation method

Objective, reasonable, and well-generalized evaluation methods are crucial for measuring technological advancements in the field of intelligent building structural design. However, certain challenges need to be addressed:

(1) In recent years, evaluation methods and indicators in this domain have exhibited inconsistency and incompleteness. The existing evaluation criteria often struggle to comprehensively and objectively reflect the mechanical performance, adherence to empirical rules, and economic efficiency of structural design. The rationality and rigor of evaluation indicators play a crucial role in determining the practical applicability of AI-based intelligent design outcomes in engineering practice. Moreover, encoding these complex evaluation criteria into executable computer code poses difficulties, hampering automated evaluation processes.

(2) AI model training requires the use of differentiable loss functions within the framework of deep learning. However, the calculation processes for indicators like mechanical performance, adherence to empirical rules, and economic efficiency in building structural design are generally non-differentiable. This poses a challenge in effectively incorporating domain knowledge into loss functions to guide generative AI learning. Hence, there is an urgent need for research focusing on universal and objective AI design evaluation methods and indicators, as well as the development of more generalizable techniques for constructing differentiable loss functions in the field.

Addressing these challenges will pave the way for the establishment of consistent, comprehensive, and objective evaluation methods and indicators in intelligent architectural structural design. This, in turn, will enable more effective assessment of AI-generated designs and facilitate their seamless integration into practical engineering applications.

6. Integration of intelligent generation and optimization

Generative AI has significant advantages in efficiently learning from design data and generating new designs. However, it has limitations in terms of design accuracy owing to its probabilistic nature based on high-dimensional feature mapping, which is not a deterministic design method. As a result, it can be challenging to accurately satisfy the requirements of relevant design specifications in local details. To address this limitation, an effective method is to combine generative AI with optimization methods to efficiently converge the design to meet specification requirements while satisfying the relevant design experience. Specifically, generative AI is used to generate designs, and optimization algorithms are applied to adjust the generated designs based on the specifications. Another approach is using deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to combine generative evaluation, optimization, and learning into an algorithm to achieve better design performance and accuracy. However, the design efficiency of the approach requires further improvement.

6.1 Two-stage design with generative AI and optimization

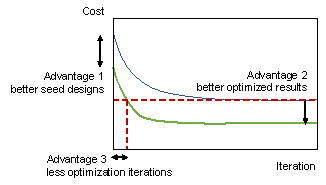

Chang and Cheng (2020) proposed a design method that combined generative AI with genetic algorithms, where the design results of generative AI were used as seed solutions. The advantages of this method are illustrated in Figure 7. The seed solutions generated by the AI were closer to the optimal value than those generated by random sampling (Advantage 1). Because AI can generate multiple seed solutions close to the optimal solution, the quality of optimization by genetic algorithms can be further improved, and the convergence of the solution is better (Advantage 2). Because AI generates excellent seed solutions, the number of iterations required to reach the optimal solution level for random seed optimization is significantly reduced (Advantage 3).

Figure 7 Advantage of using generative AI-designed results as seed solutions in the field of intelligent design for building structures (Chang & Cheng, 2020)

Fei et al. (2023a) proposed a self-learning method for the intelligent design of building structures involving AI generation, genetic algorithm optimization, and AI relearning. This method addresses the challenges of small data sizes and significant long-tail distributions in the intelligent building structure design. Specifically, the method first learns the design rules based on existing small data samples using generative AI. After training, generative AI can generate multiple design results. Subsequently, the genetic algorithm optimizes the newly generated designs to obtain additional high-quality learning samples, enlarging the original dataset. Finally, the updated dataset was used for AI learning to improve design quality. It is worth noting that, during the optimization process, the design of the shear wall component cross-sectional size can be facilitated by the work of Feng et al. (2023b). Furthermore, the quantification of construction material can be achieved through the implementation of an AI-predicting method proposed by Fei et al. (2023b).

6.2 Design generation and optimization based on deep reinforcement learning (DRL)

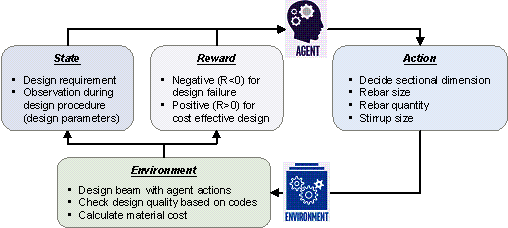

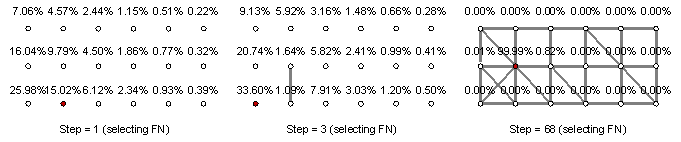

DRL is a self-learning technology that consists of an agent and an environment. It is characterized by the interaction between the agent and the environment, with the agent learning from the feedback provided by the environment (Sutton, 2019). As shown in Figure 8, the DRL process can be described as follows: (1) at each time step, the agent interacts with the environment and receives a high-dimensional observation, which is used to obtain a specific state representation using deep learning methods; (2) based on the expected return, the value function of each action is evaluated, and a specific policy is used to map the current state to the corresponding action; and (3) the agent takes action, and the environment responds by providing a reward signal, which is used to update the agent's policy and value function. The next observation is made, and the process continues iteratively to optimize the agent's behavior and achieve a specific goal. DRL has been adopted for the intelligent design of building structures based on the concept of (deep) reinforcement learning (Jeong & Jo, 2021; Cheng et al., 2022; Hayashi & Ohsaki, 2021 & 2022; Zhu et al., 2021; Kupwiwat et al., 2023; Luo et al., 2022a & 2022b; Sun et al., 2020).

Figure 8 Concept of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) in intelligent structural design (Jeong & Jo, 2021)

In the intelligent design of building structures, the main objects of design generation and optimization for concrete structures are the topological layout, cross-sectional dimensions of reinforced concrete (RC) components, and reinforcement design. Jeong and Jo (2021) applied DRL to optimize the reinforcement design of RC frame structures. The agent's action network model predicts subsequent design actions based on the current state of the RC components, and the agent's neural network continually learns during the process, ultimately enabling the agent to complete the RC component reinforcement design quickly. Cheng et al. (2022) performed an optimal design of a shear wall structure layout based on DRL using a convolutional neural network model to evaluate the current state of the structure and subsequently execute optimization actions.

Hayashi and Ohsaki (2021, 2022), Zhu et al. (2021), and Kupwiwat et al. (2023) proposed steel truss structure designs based on DRL by combining GNNs and reinforcement learning. The intelligent design approach characterizes the truss structure as a graph with information such as position coordinates and component cross-sectional dimensions represented as features in the graph. This facilitates the agent's observation of the current state, enabling it to execute actions accordingly. This method has been used to achieve cross-sectional dimension optimization for steel frame structures and topological generation and optimization design for steel truss structures. Figure 9 shows an example of the structural topology design. Similarly, Luo et al. (2022a, 2022b) represented truss layout generation and optimization as Markov decision processes using node positions as optimization variables and a Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) to perform truss structure layout design. To address the problem of exploding action space dimensions, kernel regression was employed to constrain the action space, effectively improving the optimization efficiency.

Figure 9 Topological generation and optimization of steel truss structures based on DRL (Zhu et al., 2021)

6.3 Summary of integration of generation and optimization

Currently, AI-generated structural designs encounter challenges in achieving optimal overall design while considering local design aspects. The data used for AI learning is primarily based on engineers' experience and may not necessarily represent the ideal design outcomes. Therefore, further algorithmic optimization is required to enhance the quality of AI-generated designs. However, there exists a gap between AI generation and design optimization:

(1) The data format generated by AI differs from the mechanical modeling data format necessary for optimization calculations, necessitating better coordination in transferring data between these two stages.

(2) Deep reinforcement learning and conventional optimization algorithms entail extensive search spaces and action spaces, resulting in lengthy optimization processes and difficulties in effectively meeting the requirements of the design stage. Additionally, the optimization results may not accurately reflect the design experience of engineers, making it challenging to directly apply current optimization designs in complex real-world projects.

(3) It is essential to establish a generative-optimization-relearning pathway, where generative AI and optimization algorithms collaborate to generate designs, optimize them, and continuously learn from the optimized results. This iterative process allows for automatic improvement and refinement.

Hence, future research needs to address these challenges to strike a balance between design accuracy and efficiency.

7. Application of generative AI-based design for building structures

7.1 Development of intelligent structural design systems

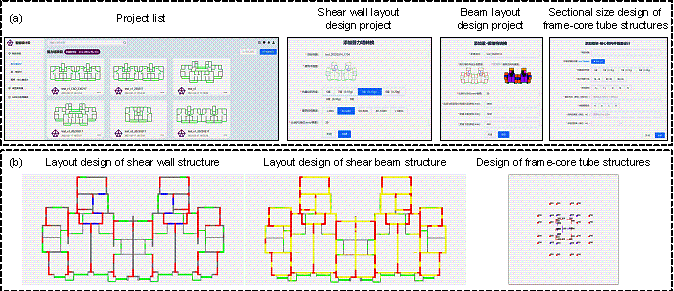

A cloud design system can be constructed based on generative AI design methods for building structures (Fei et al., 2022a). As illustrated in Figure 10(a), the users can create the design project of the shear wall layout, beam layout, and cross-sectional size of the frame-core tube structural components. Subsequently, generative AI can complete the corresponding structural scheme design by inputting the architectural scheme and design conditions as required (Figure 10(b)). The structural scheme can then be imported into CAD drawing and structural analysis software (such as Autodesk CAD, PKPM, or YJK) using a parametric modeling system. This allows for the efficient completion of structural scheme verification and construction design. Therefore, the design process, from the architectural scheme to the preliminary construction drawing, can be accomplished within 20 min, thus significantly improving the design efficiency.

Figure 10. Intelligent structural design system. (a) Design platform; (b) typical design outcomes of intelligent design.

7.2 Application and cases

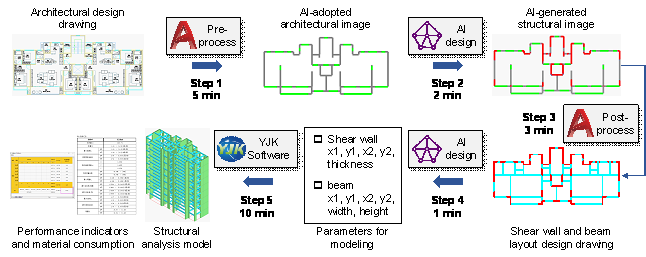

Feng et al. (2023a) proposed an intelligent design method for shear wall structure schemes that met the requirements of project bidding, including shear wall layout design and optimization, component cross-sectional design, and automated construction of structural analysis models. This study achieved an intelligent and highly automated process, from architectural to structural design drawings, structural analysis models, and material consumption statistics (Figure 11). The method was applied to a project bidding process, and the results indicated that, for a single building, the generative AI-based structural design efficiency was nearly 10¨C15 times higher than that of manual design. Moreover, the intelligent design method can simultaneously conduct multiple project designs, with the structural mechanical performance of the intelligent design meeting code requirements and the material usage almost identical to that of the engineer-designed structure.

Figure 11 Application of generative AI-based design for building structure (Feng et al., 2023a)

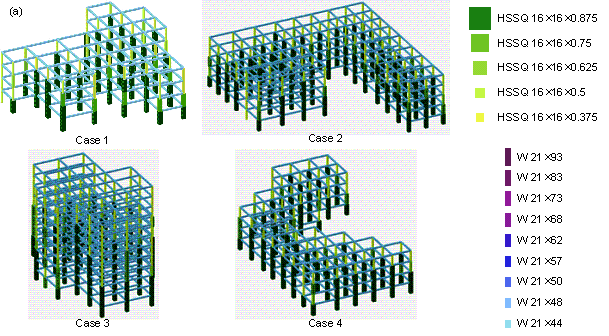

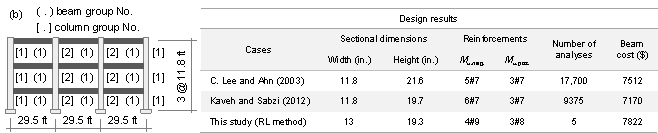

Additionally, Chang & Cheng (2020) conducted a case study focusing on the rapid design of component cross-sectional dimensions for different steel frame structures. They employed the GNN-based NeuralSim and NeuralSizer modules proposed in their research. Figure 13(a) showcases multiple design options, with a training time of approximately 2.5 hours. However, once trained, the NeuralSizer module can generate a new design in just 10.07 milliseconds, effectively incorporating the constraints of NeuralSim and demonstrating the algorithm's generalization capability. Another noteworthy study by Jeong & Jo (2021) utilized deep reinforcement learning to generate and optimize frame beam design. They applied this method to a two-dimensional, three-story, three-span reinforced concrete frame structure, as depicted in Figure 13(b). In comparison to genetic algorithms (GA) (C. Lee and Ahn, 2003) and the BB-BC algorithm (Kaveh and Sabzi, 2012), Jeong & Jo's (2021) proposed method requires minimal iteration, effectively learns from existing design data, significantly enhances efficiency, and achieves material usage comparable to results obtained through long-term optimization.

Figure 12 Typical generative AI-based design cases. (a) Design case of a steel frame structure (Chang & Cheng, 2020). (b) Design case of a concrete frame structure (Jeong & Jo, 2021).

8. Discussion

8.1 Level of generative AI design for building structure

Widespread studies and applications of generative AI in the structural design of buildings have led to significant progress in this field. To better understand the current research status and future development potential, it is suggested that the degree of generative AI involvement be divided into hierarchical levels from L0 to L5.

The L0 level (completely manual design) refers to a structural design entirely controlled by engineers. The design process depends entirely on human expertise and experience at this level.

The L1 level (human-led, AI-assisted) refers to the AI providing assistance, such as parameter optimization and rule checking for structural design. This relatively mature research and application area includes parametric modeling, intelligent optimization, and automated rule checking. The L1 level is the current general level of intelligent design, with AI assisting engineers during the design process.

The L2 level (AI-led, human-assisted at certain stages) refers to AI taking over some of the tasks in certain stages of structural design; however, it still requires human engineers to check the design results and complete other design tasks. For example, AI can complete the structural scheme design, and with the development and application of generative AI in structural design, building structural intelligent design has begun to enter the L2 level.

The L3 level (AI-led, human-assisted for specific projects) refers to the ability of AI to complete the entire structural design process of specific building projects.

The L4 level (AI-led, human-assisted for most projects) refers to AI being able to complete the entire design task for most building structures. At this level, AI can handle most design processes with minimal human intervention, significantly reducing the time and cost required for design.

The L5 level (AI-led for all projects) refers to AI being able to complete all structural design tasks for any building project. This is the ultimate goal of generative AI-based intelligent design, in which AI can handle all design aspects.

Although progress has been made in the development of levels L1 and L2, the development of levels L3¨CL5 remains in its early stages and requires further breakthroughs in AI. The development of generative AI-based intelligent design has the potential to revolutionize the building structural design process, significantly improving efficiency, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness.

8.2 Challenges

A review of existing research on generative AI in building structural design reveals that although there have been significant advancements, several critical challenges still need to be addressed. These challenges include but are not limited to

Ÿ Limited data availability: Obtaining high-quality drawings for training generative AI models is often difficult. This presents a challenge in identifying key features and discovering potential design rules for small samples.

Ÿ Sparse feature identification: Only a small proportion of the effective information on the drawing is related to the structural design. Therefore, it is essential to accurately identify, extract, and learn sparse key features to generate high-quality designs.

Ÿ Multiple constraints: Building structural design involves various constraints, including spatial layout, mechanical principles, and empirical rules. It is crucial to construct a neural network model that considers these constraints and ensures that the constraint-based loss function is differentiable.

Ÿ Complex representation: Building structural design involves the multimodal data representation of drawings, regulation texts, graphs, etc. To generate high-quality designs, information must be extracted from heterogeneous sources to represent multidimensional information.

Ÿ Strict indicators: AI-designed structures must satisfy economic indicators; otherwise, they may not be feasible for construction. Therefore, it is essential to integrate generative AI algorithms with multi-objective and multi-scale optimization algorithms to ensure the designs satisfy the required economic indicators.

Ÿ Low fault tolerance: structural design cannot lead to safety errors. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a human-in-loop evaluation strategy that integrates subjective perceptions with objective indicators to ensure that the generated designs are safe and reliable.

8.3 Future outlooks

As intelligent design research in the field of building structures continues to evolve, it is expected that the corresponding challenges will be addressed. This research outlook can be divided into two categories: technical and applicable.

(1) From a technical perspective, the following research requirements should be addressed:

Ÿ Comprehensive representation of multimodal data features and feature fusion learning to improve data representation and dataset construction; the emergence of more open-source data to improve data availability.

Ÿ Advancement of generative algorithms such as the diffusion model and large language model (LLM) (e.g., OpenAI's ChatGPT and GPT-4) to gain a deeper understanding of structural design knowledge.

Ÿ Development of universal and differentiable knowledge loss functions for design evaluation and optimization, improvement of the efficiency of the design optimization process through efficient and precise evaluation methods, and methods to reduce the action space in DRL.

(2) From an application perspective, the outlook for an intelligent design of building structures involves software, algorithms, and application foundations. To achieve intelligent design more effectively in the future, the following steps should be taken:

Ÿ Establish a digital software foundation for the design generation and analysis optimization process, using advanced digital technologies such as building information modeling (BIM).

Ÿ New intelligent algorithms should be actively adopted and combined with structural design knowledge to establish an algorithmic foundation with embedded domain knowledge.

Ÿ The industry should be encouraged to actively explore the application of intelligent design and establish an application foundation.

9. Conclusions

Generative AI-based intelligent design is an essential approach for overcoming the challenges faced by the current structural design industry, such as low design efficiency, insufficient data reuse, and difficulty in the inheriting design experience. This method learns from existing design data, understands the rules for generating structural designs based on architectural design, effectively learns the constraints of drawing and text data, as well as mechanical and empirical knowledge, and efficiently maps to generate designs. Therefore, in recent years, the research focus on intelligent design for building structures has shifted towards generative AI design based on deep learning.

Research on generative AI design for building structures has mainly focused on data feature representation and learning, intelligent generation of structural design, and effective evaluation of design results. Related research has focused on data feature representations of images and graphs. Intelligent generation algorithms have included GAN, GNN, VAE, and ANN. The design evaluation has included Turing tests, data similarity measurements, mechanical compliance, and economic evaluation.

Furthermore, an effective combination of generative and optimization methods can further integrate their advantages with the potential to significantly reduce the optimization search space, improve the optimization efficiency, and enhance the optimization quality. In addition, combining generative and optimization methods with DRL can learn through interaction with the environment, effectively reducing the time required for optimization and providing new implementation approaches for intelligent design.

Based on current generative AI design methods, the research results have been applied to create new design paradigms, including intelligent lightweight structural designs based on cloud platforms, fast material consumption estimation in bidding, and efficient scheme design paradigms based on the generation¨Coptimization¨Canalysis process.

In the future, with the development of more powerful intelligent algorithms and larger design datasets, machine intelligence will better understand the theory of building structural design. Better design results and higher levels of automation and intelligence are expected for conventional building structures, whereas AI can improve certain aspects of the design process for complex building structures. The continued development of generative AI-based intelligent design methods for building structures holds great promise for the construction industry, enabling engineers to design safer, more efficient, and more cost-effective structures.