1. Introduction

Seismic isolation is an effective method to improve the seismic resilience of buildings [1-8]. The dynamic response of the structure can be significantly reduced by installing isolation bearings at the base of the structure [9-11]. The increasing demand for seismic resilience has led to a growing demand for seismic isolation designs [3,12]. While, the prevailing artificial design approach is time-consuming and labor-cost, and unbeneficial for the advancement of seismic isolation. Therefore, intelligent and automated design is needed to improve design efficiency and give valuable design references for engineers [13-28].

The preliminary but critical seismic isolation scheme design process can significantly affect subsequent optimal designs. In scheme design, precise structural analysis is not as important as the determination of isolation bearing close to the ideal design. Engineers currently conduct seismic isolation design in the schematic phase through experience and trial-and-error, which results in low design efficiency. Thus, automated seismic (vibration) isolation design methods have been proposed and promoted to improve design efficiency through developing simplified computational models, applying optimization algorithms, and formulating objective and boundary functions [29-33]. However, existing automated design methods are more mature in terms of design optimization than the method of swiftly generating scheme designs. Furthermore, defining the objective and boundary functions and learning from existing design data are challenging to implement for automated design [34]. Consequently, existing automated design methods cannot meet the demand for efficient design during the schematic design phase. It is necessary to develop a more efficient and intelligent base-isolation design method capable of learning design principles.

With the rise of deep learning, intelligent structural design methods that can learn from existing design data are rapidly evolving, thereby opening up new possibilities [13-28]. Liao et al. [14-15], Lu et al. [16], Fei et al. [17-18], Zhao et al. [19-20], Pizarro et al. [24], and Fu et al. [25] undertook comprehensive research to develop generative adversarial network (GAN)-based intelligent design approaches for shear walls, beams, and frame-core tube structures; Chang et al. [13] and Zhao et al. [21] developed graph neural network (GNN)-based structural design methods; Hayashi et al. [26], Zhu et al. [27], and Jeong et al. [28] used reinforcement learning for structural design. Among those methods, GAN is one of the most effective and extensively utilized technologies for generating structural designs, due to its powerful generation ability. Most of the existing intelligent design methods based on deep learning rely heavily on the quality and quantity of the training data (e.g., hundreds of high-quality design drawings). However, structural design data vary by geographical area with few similar designs [35-37], and the seismic isolation design method is still under development [3,5-7], making the collection of corresponding design data extremely difficult. Thus, in the schematic phase, data-driven intelligent structural design methods are unsuitable for seismic isolation design. Furthermore, the structural design rules are also precious design knowledge in addition to design data. Nevertheless, they are also rarely utilized in the deep learning-driven intelligent design, because it is challenging to define design rules as a differentiable loss function in the deep neural network to guide training. Consequently, those obstacles, i.e., the absence of ground-truth data and methods to embed rules into deep neural network models, still prevent the deep learning-driven intelligent structural design methods from being widely adopted and developed.

Recently, a physics-enhanced GAN-based intelligent structural design method that can effectively ensure the physical performance of designs with limited data was proposed [16]. However, when applied to seismically isolated structures, the physics-enhanced intelligent design still faces the following challenges: (1) design data unavailability, resulting in the initial optimization directions being unsuitable; (2) a lack of surrogate models for seismic isolation structures; and (3) design rules that are barely satisfactory, necessitating further research. In terms of intelligent structural design, its primary objective is to enable intelligent algorithms to gradually understand the design rules of engineers through the study of mechanical principles, design rules, and data, and then to effectively assist or possibly replace engineers throughout the design phase. Furthermore, adopting intelligent design transforms the engineers-dependent design paradigm of building structures into one that automates and intelligentizes the entire design process. Therefore, these constraints must be overcome if intelligent algorithms are to acquire the ability to create design and even outperform engineers.

To this end, this study proposes a novel intelligent seismic isolation design approach for shear wall structures in the scheme design phase by using a physics-rule-co-guided self-supervised GAN, building on previous research on GAN-based intelligent structural design methods. The method was developed based on StructGAN-PHY [16], called StructGAN-Hybrid (physics-rule hybrid-driven StructGAN), as shown in Section 2. The critical components of the StructGAN-Hybrid are the physics estimator and rule evaluator, which help achieve the self-supervised learning of GANs, as shown in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Subsequently, data features and network models are discussed to enhance the design performance of the StructGAN-Hybrid, as shown in Section 5. Finally, case studies indicate that StructGAN-Hybrid can design the layout of seismic isolation bearings and the corresponding bearing parameters based on the input of shear wall structure drawings, as presented in Section 6. Furthermore, the seismic isolation design can satisfy the critical code specifications, enhance the structural seismic performance, and provide an effective scheme design for engineers.

2. Intelligent base-isolation design method (StructGAN-Hybrid)

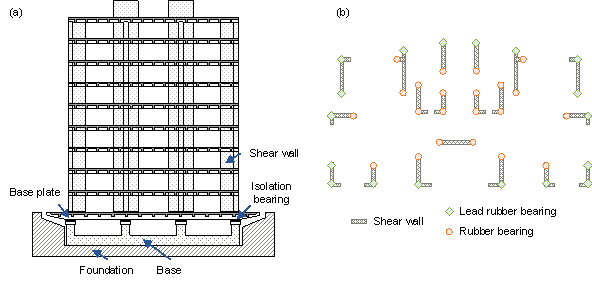

Figure 1 shows a typical seismic isolation design of a shear wall structure, where the superstructure (i.e., shear wall structure) is located on the base plate, and the base plate is connected to the seismic isolation bearing, which is supported by the foundation. Figure 1(b) shows a typical base isolation design scheme.

Figure 1 Typical seismic isolation for a shear wall structure. (a) Elevation view. (b) Plan view.

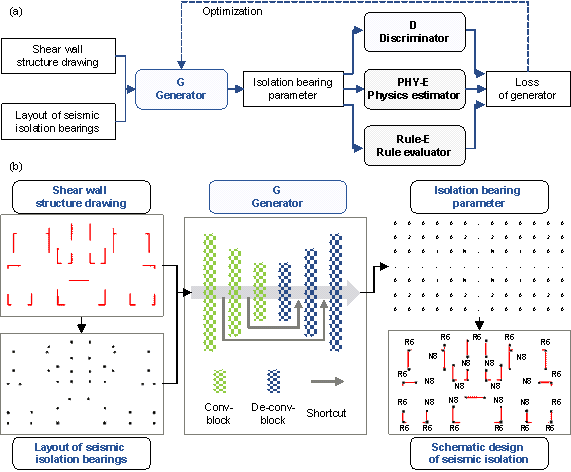

This study proposes a physics-rule-co-guided GAN (Figure 2(a)) to intelligently conduct seismic isolation design of a shear wall structure during the scheme phase. The seismic isolation bearing parameters can be generated using the proposed networks by simultaneously inputting the shear wall structure drawing and seismic isolation bearing layouts (Figure 2(b)). Unlike the conventional GAN composed of generators and discriminators, this study proposes an empirical rule evaluator and a physics estimator to co-guide the optimization of generators from both design experience and physical mechanisms, thereby improving the generator performance. Because the proposed method is unsupervised learning and there are no ground-truth target data, pseudo-labels are required for the initial training during the initial optimization of the generator to achieve better unsupervised learning performance. Furthermore, a specially designed physics estimator for seismic isolation is developed. The rule evaluator is a newly developed tensor operator to embed design rules into the GAN. In addition, the creation of pseudo-labels is novelly proposed to help the generator search initial optimization direction. Consequently, these critical contributions preliminarily solve the challenges of intelligent seismic isolation design in the scheming phase.

Figure 2 Intelligent design method of seismic isolation scheme. (a) Physics-rule-co-guided GAN. (b) Intelligent seismic isolation design based on trained generative network

Furthermore, seismic isolation design for complex structures that typically necessitates a specific detailed design is relatively difficult〞not a standard design task. Consequently, such a complex structural design is unsuitable for intelligent designs based on deep learning. Therefore, this study focuses on the seismic isolation design of regular shear wall structures, which have the following characteristics: (1) the plan and vertical layouts of shear wall structures are regular [11]; (2) the structural height每width ratio is not greater than 3, and the structural height is less than 50 m to avoid tensile stress in the isolation bearings as much as possible [11]; and (3) the seismic design intensity of the building structure is primarily at 8 degree (with a peak ground acceleration (PGA) of 10% exceedance in 50 years equaling 0.2g) and 7.5 degree (with a PGA of 10 percent exceedance in 50 years equals 0.15g). The aforementioned is attributable to the demand for seismic isolation design of such structures being quite high in practice.

2.1 Physics-rule-co-guided GAN

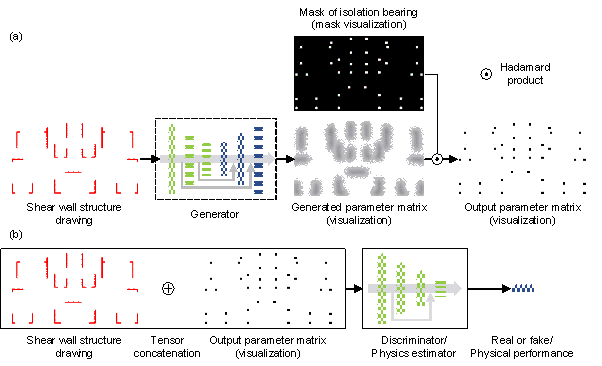

The physics-rule-co-guided network architecture is illustrated in Figure 2(a). (1) The parameter generator comprises convolutional and deconvolutional networks with shortcuts [14-16,38], where the input is a shear wall structure drawing and the output is a single-channel two-dimensional tensor. The output tensor and mask of the isolation bearing are then operated by the Hadamard product to obtain the isolation parameter tensor (Figure 3(a)). Additional information and the source codes of the generator and discriminator are provided in the study by Liao et al. [14] (2) The discriminator and physics estimator use the residual convolutional network model [14-16,38]. The shear wall structural tensor is concatenated with the bearing parameter tensor and then input into the discriminator (or physics estimator), which in turn yields the true每false (or physical performance index) (Figure 3(b)). More details of the physics estimator are presented in Section 3. (3) The rule evaluator is a tensor operator with the generated bearing parameter tensor input to obtain the discreteness of the bearing diameters and maximum subjected surface pressure of the bearings, as detailed in Section 4.

Figure 3 Networks of (a) generator, (b) discriminator, and physics estimator

2.2 Loss function and training method

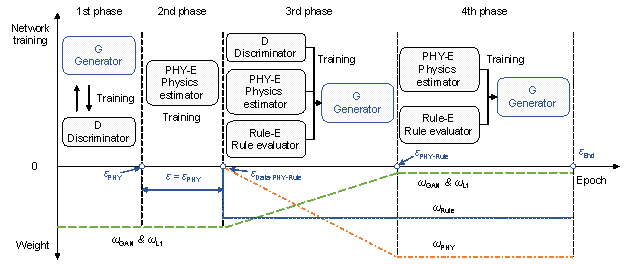

According to the proposed physics-rule-co-guided GAN, loss functions are created to optimize the generator, and the corresponding multiphase training method is proposed to solve the multiobject optimization problem. The loss function of the generator is shown in Equation (1), and multiphase training is illustrated in Figure 4. During multiphase training using pseudo-labels, physics, and rules, the weights of multiple losses are adaptively changed. The multiphase and multiweight training methods help the neural network model learn how to generate the parameter matrix of seismic isolation bearings with the co-guidance of design rules and physical performance.

![]() ,

(1)

,

(1)

where

![]() is the generator loss;

is the generator loss; ![]() and 肋GAN are the generative adversarial loss and its

corresponding weights, respectively;

and 肋GAN are the generative adversarial loss and its

corresponding weights, respectively; ![]() and 肋L1 are the L1-norm distances between the generated

parameter matrix and pseudo-label parameter matrix and its corresponding weights,

respectively;

and 肋L1 are the L1-norm distances between the generated

parameter matrix and pseudo-label parameter matrix and its corresponding weights,

respectively; ![]() and 肋PHY are the physics loss and its corresponding

weights, respectively, as detailed in Section 3; and

and 肋PHY are the physics loss and its corresponding

weights, respectively, as detailed in Section 3; and

![]() and 肋Rule are the rule loss and its corresponding

weights, respectively, as detailed in Section 4.

and 肋Rule are the rule loss and its corresponding

weights, respectively, as detailed in Section 4.

In the physics-rule-co-guided GAN, the generator should first learn to generate the bearing parameter matrix and, subsequently, design the bearing parameter more reasonably under physics and rule guidance. Therefore, this study proposes a multiphase training method in which the discriminator, physics estimator, and rule evaluator perform different roles during different training phases. The proposed multiphase training method is illustrated in Figure 4.

In the 1st phase (汍 < 汍PHY), the generator

and discriminator are first trained based on pseudo-labels using the corresponding

![]() and

and ![]() loss.

loss.

In the 2nd phase (汍 = 汍PHY), the physics estimator is trained based on the seismic isolation parameter matrix generated in the first stage and its corresponding physical performance index.

In the 3rd phase (汍PHY-Rule > 汍 > 汍Data-PHY-Rule),

namely, the data-physics-rule hybrid training phase, the weight of

![]() is gradually increased, the weights of

is gradually increased, the weights of ![]() and

and ![]() are gradually decreased, and the weight of

are gradually decreased, and the weight of ![]() is consistent, indicating that the generator is simultaneously

trained using pseudo-labels, physics, and rules.

is consistent, indicating that the generator is simultaneously

trained using pseudo-labels, physics, and rules.

In the 4th phase (汍 > 汍PHY-Rule), the physics estimator and empirical

rule evaluator dominate the training, using the corresponding ![]() and

and ![]() losses.

losses.

Figure 4 Training method of the physics-rule-co-guided GAN (汍 denotes epoch)

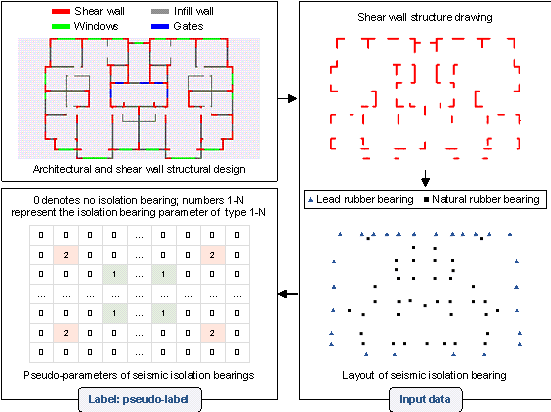

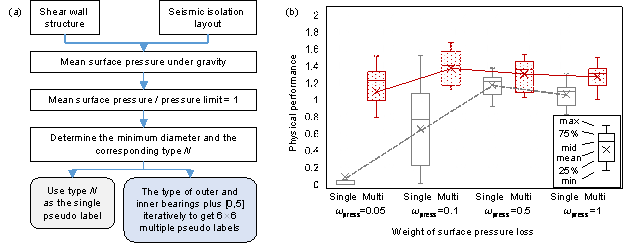

2.3 Dataset with pseudo-labels

As shown in Figure 2(b), the inputs were the layout drawings of the shear wall structural components and isolation bearings, and the output is a parameter matrix of the bearing type. The pseudo-labels are the parameter matrix and are created as shown in Figure 5, including the acquisition of shear wall structure data, layout design of seismic isolation bearings, and generation of seismic isolation bearing pseudo-parameters. Pseudo-labels are used as the target data for the initial training of the generative networks, which are created based on the empirical rules of seismic isolation design (i.e., the isolation bearing diameter can be preliminarily determined based on the surface pressure under gravity load). Thus, the creation of pseudo-labels is an essential rule-driven method. Note that StructGAN-Hybrid is an unsupervised learning method, so there is no need to create a test set.

Both engineer-designed and AI-based design outcomes can be adopted to acquire shear wall layout data [16]. Subsequently, to determine the seismic isolation bearing locations, the bearings can be arranged at the ends of the shear wall components by automatically extracting the coordinates of the component ends [16]. If the surface pressure of the bearing cannot meet the design specifications, an additional isolation bearing is appropriately added in the middle of the shear wall [11]. Finally, for the generation of a bearing pseudo-parameter, (1) lead rubber bearings are more suitable for the outer bearings to dissipate more seismic energy, and rubber bearings are more suitable for the inner bearings to reduce the story stiffness and construction cost. Moreover, such a layout reduces the torsion effect [6-7]. (2) The average gravity load of each bearing is dependent on the building self-weight divided by the number of isolation bearings, and the diameter of the isolation bearing is then determined according to the maximum allowed surface pressure. Note that the seismic isolation bearing diameter has a one-to-one correspondence with the bearing parameters, meaning that the bearing diameter can determine all bearing parameters.

In addition, if the seismic isolation bearing is represented by only one pixel, it can easily cause the disappearance of features during the convolutional process of the neural network. Therefore, in this study, a square matrix is adopted to denote the isolation bearing, with the bearing center being the central coordinate of the matrix. The matrix area is nisopix (i.e., the number of matrix pixels), and a reasonable value of nisopix is discussed in Section 5. The input image size is 512 ℅ 256, which is consistent with the results of Liao et al. [14] and Lu et al. [16].

Figure 5 Dataset establishment

2.4 Evaluation method

After physics and rule co-guided training, an evaluation is necessary to assess the seismic isolation design performance. Accordingly, this study employed both a multi-degree-of-freedom (MDOF) model and a finite element model-based evaluation method. The MDOF model with high computational efficiency and moderate accuracy is suitable for evaluating many design results, which will be described in detail in Section 3, and the corresponding performance indices will be given in Section 5. Notably, the finite element model with high computational accuracy and low efficiency is suitable for analyzing and validating typical design results.

3. Physics estimator

3.1 Physical performance calculation model

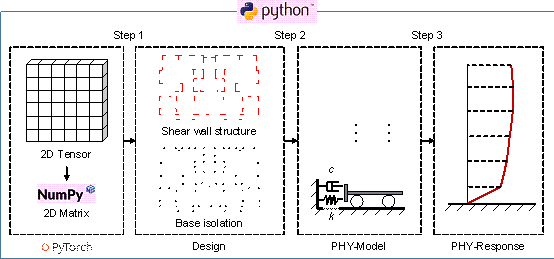

In StructGAN-Hybrid, the physics estimator is critical. It is a surrogate model based on deep neural networks trained to map the seismic isolation design to its corresponding physical performance index. To train the physics estimator, the physical performance calculation model of isolated shear wall structures is first established, and then the physical performance index is obtained by calculating the physical models generated by the generator. The calculation is based on the complex modal response spectrum analysis method provided in the Chinese seismic isolation design code [39]. Finally, based on the generated seismic isolation designs and the corresponding physical index, datasets for the physics estimator are created. The heterogeneous data transformation and physical performance calculation methods in the Python framework are shown in Figure 6.

Step 1: Convert the tensors generated by Pytorch into matrices supported by Numpy to transform heterogeneous data.

Step 2: Establish the MDOF model using the parameters of the upper shear wall structure and isolation bearings, that is, the PHY-Model.

Step 3: Obtain the dynamic responses of the structures under the design-based earthquake (DBE, 10% exceedance in 50 years) and maximum considered earthquake (MCE, 2% exceedance in 50 years) using the MDOF models. Then, the physical performance indices of the structures are calculated according to the dynamic responses.

Figure 6 Physical performance calculation method under the Python framework

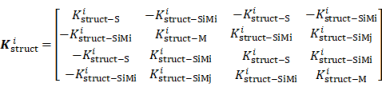

The MDOF model of isolated structures includes the stiffness matrix

and mass matrix, which are jointly determined by the parameters of the superstructure

and isolation layer. Ma et al. [40] showed that if the flexural deformation

of the superstructure of a base-isolated high-rise building is ignored, the

dynamic response of the structure may be underestimated. Therefore, the widely

used MDOF flexural-shear model [41-44] is used for the superstructure of the

isolated building in this study, and the corresponding parameters were calibrated

according to Lu et al. [16]. The parameters of the isolation layer were selected

based on the isolation bearing [6-7]. Equations (2)每(4) are used to calculate

the stiffness matrix (KBI) and mass matrix (MBI)

of the base isolation layer, respectively. Equations (5) and (6) are used

to calculate the mass matrix ( ![]() ) and stiffness matrix (

) and stiffness matrix ( ![]() ) of the i-th story of the superstructure, respectively.

) of the i-th story of the superstructure, respectively.

![]() ,

(2)

,

(2)

![]() ,

(3)

,

(3)

![]() ,

(4)

,

(4)

where ![]() is the horizontal shear stiffness of the isolation layer,

is the horizontal shear stiffness of the isolation layer,

![]() is the horizontal shear stiffness of the i-th isolation

bearing, and n is the number of isolation bearings. In this study,

because the height每width ratio of the structure is limited (< 3), the flexural

deformation of the isolation layer can be ignored, and the isolation layer

is considered to be under pure shear. MBI is the mass of

the isolation layer.

is the horizontal shear stiffness of the i-th isolation

bearing, and n is the number of isolation bearings. In this study,

because the height每width ratio of the structure is limited (< 3), the flexural

deformation of the isolation layer can be ignored, and the isolation layer

is considered to be under pure shear. MBI is the mass of

the isolation layer.

,

(5)

,

(5)

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

,

(6)

,

(6)

where ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are the mass, sum of equivalent flexural stiffness, sum

of equivalent shear stiffness, and story height of the i-th story of

the superstructure, respectively.

are the mass, sum of equivalent flexural stiffness, sum

of equivalent shear stiffness, and story height of the i-th story of

the superstructure, respectively.

A dynamic analysis of the structure can be performed based on the MDOF model of isolated structures. Notably, although the superstructure is basically in an elastic state under the DBE, the damping characteristics of the isolation layer are different from those of the superstructure. Therefore, the model is a non-proportional damping linear system [45-46]. The Rayleigh damping model is adopted in the damping matrix, and the Rayleigh damping of the i-th story is given by Equation (7).

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(7)

,

(7)

where CBI is the damping matrix of the isolation

layer; ![]() is the damping matrix of the i-th story of the superstructure;

and 汐BI and 汕BI, and 汐struct

and 汕struct are the stiffness factor and mass factor of

the damping matrices of the isolation layer and the superstructure, respectively.

is the damping matrix of the i-th story of the superstructure;

and 汐BI and 汕BI, and 汐struct

and 汕struct are the stiffness factor and mass factor of

the damping matrices of the isolation layer and the superstructure, respectively.

(1) Structural dynamic response analysis. The complex mode decomposition

method was adopted, and the state-space matrices were formulated from the

stiffness matrix, mass matrix, and damping matrix. Eigenvalue decomposition

is performed based on the state space to solve the complex mode and corresponding

complex eigenvalues [44-45]. Response spectrum analyses under DBE and MCE

were performed according to the Chinese Standard for Seismic Isolation Design

of Buildings [39]. Owing to their nonlinear characteristics, isolation bearings

exhibit different stiffness and damping behaviors under different deformations.

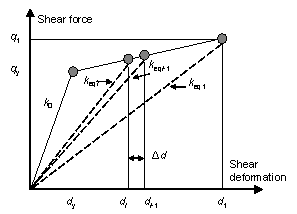

Therefore, the equivalent linearization method (Figure 7 and Equations (8)每(9))

was used to solve the equivalent stiffness (keq) and equivalent

damping (缶eq) of the isolation bearing under the given deformation.

Specifically, we first assume that the DBE deformation is d1

and calculate keq1 and 缶eq1 corresponding

to that deformation. Subsequently, we iteratively calculate the seismic deformation

di and the corresponding keqi and

缶eqi

until convergence (i.e., ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

![]() ,

(8)

,

(8)

![]() ,

(9)

,

(9)

where k0 denotes the initial stiffness, ky denotes the post-yielding stiffness, qy denotes the yielding shear force, dy denotes the yielding deformation, d1 denotes the assumed initial deformation, [竹d] denotes the deformation convergence threshold, and [竹缶] denotes the damping convergence threshold.

Figure 7 Iterative calculation model of isolation layer performance

(2) Physical performance index. According to the requirements of the Chinese Code for Seismic Design of Buildings [47] and Standard for Seismic Isolation Design of Buildings [39], this study considers the seismic reduction factor (汕reduce), maximum isolation layer displacement (uBIh), and maximum inter-story drift ratio (牟drift) as the performance indices. Specifically, 1) the seismic reduction factor (汕reduce) is the shear force and bending moment ratio of the structure under the DBE with and without base isolation. 2) The maximum isolation layer displacement uBIh and maximum inter-story drift ratio 牟drift were calculated under the MCE. Notably, a smaller 汕reduce or a greater uBIh and 牟drift represent a better seismic isolation performance within the permitted range of the design codes.

The code limits are given by Equation (10). Notably, the numerical values of the physical performance indices in Equation (10) are at different scales. Therefore, the physical performance indices used in this study are normalized as shown in Equation (11).

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(10)

,

(10)

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(11)

,

(11)

where [汕] is the seismic reduction factor limit, which is 0.5, according to the Chinese code [39]; [u] is the deformation limit of the isolation layer, which is the minimum value of 0.55 times the diameter and 3 times the total thickness of the rubber layer (taking the smallest isolation bearing as the lower limit) [39]; and [牟] is the inter-story drift ratio limit of the superstructure, which is 1/250 according to the Chinese code [39].

(3) Accuracy of physical performance calculation

After presenting a construction and analysis approach for the MDOF model with base isolation, this work uses the ETABS model's calculation results to validate its accuracy. Notably, this research has not yet collected ETABS models designed and optimized by engineers for the seismic isolation design of shear wall structures. As a result, the parametric modeling method is used to create approximately 50 ETABS models with various isolation bearing arrangements and upper shear wall structures. Moreover, in the MDOF and ETABS models, the mechanical model of lead rubber bearings (LRB) uses a bilinear model (shown in Figure 7), and the mechanical model of natural rubber bearings (NRB) is linear. The equivalent linearization method of Equations (8) and (9) is used to derive the equivalent stiffness and damping of the LRB model.

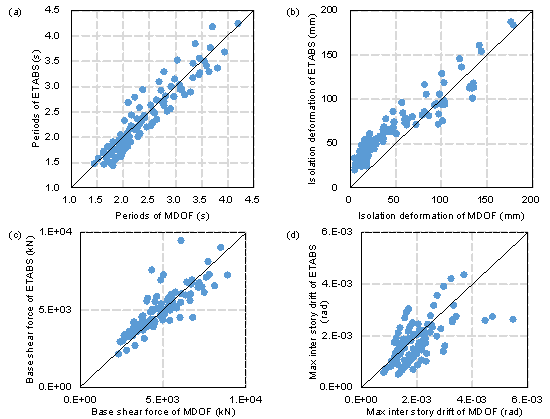

Figure 8 depicts the outcomes of the accuracy evaluation, including mechanical response in both the x and y directions. The dynamic characteristics of the MDOF model are essentially identical to those of the ETABS model, as shown in Figure 8(a), with an approximate 8% difference. Second, the calculation of the seismic reduction factor is critical for seismic isolation design; thus, the calculation accuracy of the base shear force is moderate and meets the criteria with a 15% error (shown in Figure 8(b)). Figures 8(c) and (d) show the maximum deformation of the isolation bearings and the maximum inter-story drift ratio, respectively. The prediction accuracy of MDOF is slightly lower, with an error of approximately 35%; however, because the deformation limit can always be satisfied in the isolation structure design, the error of deformation prediction is not critical and can meet the requirements.

Figure 8 MDOF model calculation accuracy. (a) dynamic characteristic. (b) maximum isolation bearing deformation. (c) base shear force. (d) maximum inter-story drift ratio

3.2 Physics estimator model

Lu et al. [16] collected hundreds of different shear-wall structures. Various seismic isolation designs have been installed in these shear wall structures. Using the physical performance calculation model, physical performance can be evaluated based on the generated possible isolation designs. Thus, a dataset with 7200 training cases and 4000 test cases is generated, in which the isolation designs and corresponding normalized physical performance indexes are used as inputs and labels, respectively. Subsequently, Lu et al. [16] proposed using the widely adopted ResNet18 deep neural networks as the physical performance prediction model (i.e., physics estimator) (Figure 3). The performance of the ResNet18-based physics estimator was analyzed using the established dataset.

Three physical performances (i.e., 汕reduce, uBIh, and 牟drift) must be estimated. Consequently, there are two strategies for creating ResNet18-based physics estimators. 1) Use a single model to predict three physical performances simultaneously. 2) Use three independent models to predict the corresponding physical performance separately. These two strategies are analyzed and compared in Table 1. It can be observed that using three models results in higher prediction accuracy. Compared with using a single model, the average prediction accuracy of using the three models increased by at least 59%. Therefore, this study uses the three models as physics estimators.

Table 1 Prediction accuracy analysis of physics estimator

|

Prediction accuracy |

Seismic reduction factor (汕reduce) |

Maximum isolation |

Maximum inter-story |

||||||

|

One model |

Three models |

Improve-ment |

One model |

Three models |

Improve-ment |

One model |

Three models |

Improve-ment |

|

|

Mean |

31% |

12% |

59% |

12% |

5% |

59% |

28% |

9% |

67% |

|

Std |

37% |

12% |

37% |

5% |

54% |

9% |

|||

Mean denotes the average value, and Std denotes standard deviation.

The corresponding physical performance loss function ( ![]() ) was calculated based on the normalized physical performance indices

predicted by the ResNet18-based physics estimators, as shown in Equation (12).

The seismic reduction factor (a smaller value is better) is the primary index

for measuring the effect of the seismic isolation design. The displacement

of the isolation layer and the inter-story drift ratio of the superstructure

are the constraints that must be satisfied according to the design codes.

The threshold function is used to transform the predicted performance indices

into a penalty function, which is larger than 0 when the code limit is exceeded

and 0 otherwise.

) was calculated based on the normalized physical performance indices

predicted by the ResNet18-based physics estimators, as shown in Equation (12).

The seismic reduction factor (a smaller value is better) is the primary index

for measuring the effect of the seismic isolation design. The displacement

of the isolation layer and the inter-story drift ratio of the superstructure

are the constraints that must be satisfied according to the design codes.

The threshold function is used to transform the predicted performance indices

into a penalty function, which is larger than 0 when the code limit is exceeded

and 0 otherwise.

![]() ,

(12)

,

(12)

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(13)

,

(13)

![]() ,

(14)

,

(14)

where 肋汕, 肋u, and 肋牟

are the weights of the performance indices of the seismic reduction factor,

isolation layer displacement, and inter-story drift ratio, respectively;

![]() and

and ![]() are the normalized seismic reduction factors predicted

by the physics estimators and its corresponding performance index;

are the normalized seismic reduction factors predicted

by the physics estimators and its corresponding performance index; ![]() and

and ![]() are the normalized isolation layer deformations predicted

by the physics estimators and its corresponding performance index;

are the normalized isolation layer deformations predicted

by the physics estimators and its corresponding performance index; ![]() and

and ![]() are the normalized inter-story drift ratios predicted by

the physics estimators and its corresponding performance index; and FThreshold(∙)

is the threshold function provided by Pytorch for tensor computation torch.nn.functional.threshold(threshold,

value, inplace=False) [48], threshold=1, value=0.

are the normalized inter-story drift ratios predicted by

the physics estimators and its corresponding performance index; and FThreshold(∙)

is the threshold function provided by Pytorch for tensor computation torch.nn.functional.threshold(threshold,

value, inplace=False) [48], threshold=1, value=0.

4. Empirical rule evaluator

In addition to physical mechanisms, empirical design rules play an important role in structural design. In this study, empirical design rules are embedded in neural networks by formulating the corresponding loss functions to optimize the network parameters through backpropagation. By directly operating the tensors in the computation graph of deep neural networks, the computation process becomes differentiable and part of the computation graph, thereby ensuring the effectiveness of backpropagation. The design code requirements and design experience are as follows:

1) Because the maximum allowable deformation of the isolation layer is determined by the bearing with the smallest diameter [39,47], the diameters of the isolation bearings should be as consistent as possible to minimize performance uncertainty during design, manufacture, and maintenance.

2) Lead rubber bearings and rubber bearings are preferably placed on the outer and inner locations of the isolation layer, respectively. Thus, the torsion of the structure can be better controlled [5-7].

3) The maximum surface pressure requirement of the bearings can be satisfied under the gravity load [39,47].

Based on existing empirical rules and deep learning computation mechanisms, this study establishes an empirical rule evaluator by formulating the corresponding loss functions and calculating the losses from the tensors. Rules 1) and 2) are combined to formulate the performance function for the bearing diameter difference (pdiam). Rule 3) is formulated as a performance function of bearing surface pressure (ppress).

(1) Performance function of bearing diameter difference (pdiam, Equation (15)). Prebuild the bearing classification masks (in the format of tensors) of the bearings on the outer and inner locations of the seismic isolation layout. The diameters of the bearings on the outer and inner locations were extracted using the Hadamard product on the masks and the generated bearing-diameter tensors. The differences between a specific bearing diameter and the average bearing diameter for both the outer and inner locations can be calculated using Equations (16) and (17).

![]() ,

(15)

,

(15)

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(16)

,

(16)

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(17)

,

(17)

where Dout and Din are the deviations

of the bearing diameters at the outer and inner locations, respectively;

![]() and

and ![]() are the j-th pixels corresponding to the diameter

of the i-th bearing on the outer and inner locations, respectively;

are the j-th pixels corresponding to the diameter

of the i-th bearing on the outer and inner locations, respectively;

![]() and

and ![]() are the average bearing diameters of all pixels on the

outer and inner locations, respectively; nout and nin

are the numbers of bearings at the outer and inner locations, respectively;

and nisopix is the number of pixels representing an isolation

bearing.

are the average bearing diameters of all pixels on the

outer and inner locations, respectively; nout and nin

are the numbers of bearings at the outer and inner locations, respectively;

and nisopix is the number of pixels representing an isolation

bearing.

(2) Performance function of the bearing surface pressure (ppress, Equation (18)). Obtain the average diameters of all isolation bearings from the prebuilt tensor masks. Divide the total weight of the structure onto each isolation bearing and consider the nonuniform distribution of gravity using an amplification factor, thereby obtaining the vertical loads on the bearings (Equation (19)). Finally, calculate the surface pressure ppress according to the vertical load and diameter of the bearing.

![]() ,

(18)

,

(18)

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

(19)

,

(19)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the average surface pressures of bearings on the outer

and inner parts, respectively;

are the average surface pressures of bearings on the outer

and inner parts, respectively; ![]() is the maximum surface pressure limit of the isolation

bearings, which is 15 MPa according to the Chinese code [39]; Giso

is the average vertical load on a single bearing; and 污G

is the amplification factor that considers the nonuniform distribution of

gravity loads, which is conservatively taken as 污G = 2.5,

according to the statistical results.

is the maximum surface pressure limit of the isolation

bearings, which is 15 MPa according to the Chinese code [39]; Giso

is the average vertical load on a single bearing; and 污G

is the amplification factor that considers the nonuniform distribution of

gravity loads, which is conservatively taken as 污G = 2.5,

according to the statistical results.

(3) Loss function of empirical rules ( ![]() ). From the bearing diameter difference performance function and the

surface pressure performance function, the loss functions of the empirical

rules can be obtained, as shown in Equation (20).

). From the bearing diameter difference performance function and the

surface pressure performance function, the loss functions of the empirical

rules can be obtained, as shown in Equation (20).

![]() ,

(20)

,

(20)

where 肋diam and 肋press are the weights of the bearing diameter difference performance function and surface pressure performance function, respectively, which are discussed in Section 5.2.

5. Discussion on data features and neural networks

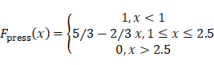

The physics and design rules were adopted to co-guide the unsupervised learning of StructGAN-Hybrid. The creation of pseudo-labeled data, deep neural networks, and the corresponding loss can primarily affect design performance. Therefore, the critical effect factors are analyzed and discussed in this section. The dataset used for the discussion was constructed according to the method in Section 2.3, with a total of 18 cases, where the seismic design intensity is 8 degree, and the structural height is 50 m. Moreover, the performance evaluation index is shown in Equations (21)每(22), with a higher index representing a better performance of the structure. When the index is greater than one, the design results satisfy the design specifications.

![]() (21)

(21)

![]() ,

,  (22)

(22)

where ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are shown in Equation (11); ppress is

given by Equation (18); Fpress(x) denotes the pressure

performance index.

are shown in Equation (11); ppress is

given by Equation (18); Fpress(x) denotes the pressure

performance index.

5.1 Analysis of data features

(1) Pixel range of isolation bearings (nisopix)

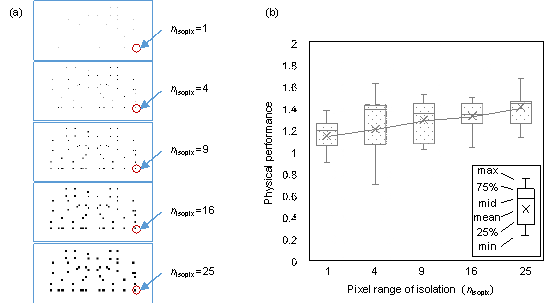

The vanishing gradient problem occurs during the convolution-based deep feature extraction process, and this study adopted residual networks to overcome this problem [49-50]. However, if the pixels of the data features are too sparse, the feature vanishing problem during the convolutional process is still prominent. Hence, this study used multiple pixels to represent the seismic isolation bearing, and a parametric analysis was conducted to determine the suitable pixel range (nisopix) of the seismic isolation bearing. The typical data are shown in Figure 9(a).

The impact of pixel range (nisopix) is shown in Figure 9(b). As nisopix increases, the physical performance of the design becomes more stable (i.e., more minor deviations) and gradually improves. However, when the pixel range is too extensive, it causes an overlapping problem for different bearing pixels. Therefore, in this study, the recommended pixel range (nisopix) is [9, 25].

Figure 9 Analysis of pixel range of isolation. (a) Typical data. (b) Analysis results.

(2) Effect of multi-pseudo-labeled data.

In the first training phase, generator learning primarily relies on pseudo-labeled data. The creation of pseudo-labeled data significantly affects the diversity of the generator learning. To this end, this study analyzed the effects of single and multiple pseudo-labeled datasets. The single pseudo-labeled dataset denotes one shear wall structure, and its seismic isolation layout corresponds to only one pseudo-label. In contrast, multiple pseudo-labeled datasets denote one shear wall structure, and the seismic isolation layout corresponds to multiple (up to 36) pseudo-labels. The establishment of single and multiple pseudo-labeled datasets is shown in Figure 10(a). Subsequently, based on the created datasets, training and testing were conducted and compared.

The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 10(b). The physical performance of the generated designs trained using multiple pseudo-labeled datasets was significantly better than that trained using single pseudo-labeled datasets. The mean physical performance of the former is better, and the deviation in the former is minor under different weights of bearing pressure performance. This is attributable to multiple pseudo-labels providing more feasible solutions for the generator in the first stage of training, broadening the optimization search domain, and generating more diverse physical models with corresponding performance indices, which is beneficial for the training of the physics estimator and guiding the generator optimization.

Figure 10 Influence analysis of single and multiple pseudo-labels. (a) Single and multiple pseudo-labels establishments. (b) Analysis results

5.2 Analysis of network and loss weight

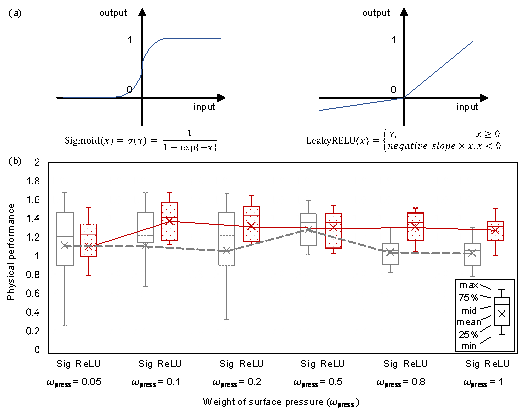

Lu et al.'s [16] study on the physics estimator indicated that the activation function of the output layer and the weight of the rule evaluator significantly affect the design results.

(1) Activation function of the output layer

The generator output is the tensor of the bearing diameter parameter with one channel, and the tensor parameters must be positive. Therefore, the Sigmoid and LeakyReLU functions are chosen as the activation functions of the output layer, as shown in Figure 11(a) [48]. The performance analysis of different activation functions is shown in Figure 11(b). The performance of the LeakyReLU activation function is better than that of the Sigmoid function, mainly because using the Sigmoid function is prone to causing a vanishing gradient when the output value is close to 0 or 1.

(2) Weight of the bearing pressure performance (肋press in Equation (20))

The proposed rule loss is determined by both the bearing diameter performance and weight (i.e., pdiam and 肋diam), and the bearing pressure performance and weight (i.e., ppress and 肋press) (shown in Equation (20)). The training phase using pseudo-label datasets can result in the generator learning to output the bearing diameter as consistently as possible; therefore, its corresponding weight (肋diam) has little effect. In contrast, the weight of the bearing pressure loss (肋press) can significantly affect the design performance. Therefore, a parametric study was conducted to determine the most suitable weight, as shown in Figure 11(b). Overall, 肋press = 0.1, resulting in the best performance.

Figure 11 Discussion on network models and rule-based loss. (a) Sigmoid and LeakyReLU activation functions. (b) Analysis results of the activation function of the output layer and the weight of pressure loss (Sig and ReLU denote Sigmoid and LeakyReLU (negative_slope=0.05) functions, respectively)

6. Case studies

6.1 Case studies under different design conditions

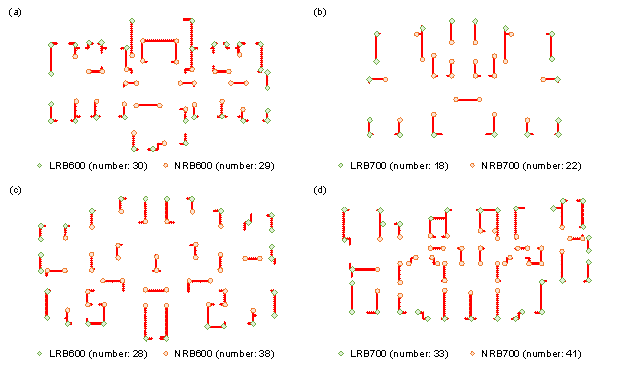

In this study, 75 cases of shear-wall buildings were collected under different design conditions [14-16]. The seismic design intensities and structural heights were 7.5 degree and 50 m (total of 18 cases), 7.5 degree and 30 m (total of 29 cases), 8 degree and 50 m (total of 10 cases), and 8 degree and 30 m (total of 18 cases), respectively. From the layout drawings of the shear walls, the corresponding seismic isolations were designed using the proposed StructGAN-Hybrid. The calculation of mechanical response for 75 cases adopts the method outlined in Section 3.1, the models employ the simplified MDOF model, and the analysis of structural dynamic response employs the complex modal response spectrum analysis method specified by the seismic isolation design code [39]. Based on the results of the mechanical analysis, the performance of the corresponding designs was evaluated using Equation (21). The results are listed in Table 2, and typical seismic isolation designs are shown in Figure 12. The integrated physical performance indices of the design results are all greater than 1, which means that the StructGAN-Hybrid-generated designs adhere to the design codes, and the physics and rule loss functions effectively guide the training.

A detailed discussion on the typical design results in Figure 12 shows that (1) for each case, the diameters of outer and inner seismic isolation bearings are consistent , indicating that the rule of diameter consistency effectively guides the design; (2) with increases in the structural height, the corresponding greater gravity causes an increase in the bearing surface pressure, so the bearing diameters increases, indicating that the rule of bearing pressure requirement effectively guides the design; (3) with changing seismic intensity, the seismic isolation bearing parameters change marginally, primary because 1) the seismic load of 8 degree is larger than that of 7.5 degree, and the bearings diameters should be larger, 2) the floor area of the cases in the two seismic design conditions are not markedly different, but the number of seismic isolation bearings for the 7.5 degree cases (Figures 11(a) and (b)) are approximately half those of the 8 degree cases (Figures 11(c) and (d)), which means the pressure of bearings in the 7.5 degree cases are greater than those in the 8 degree cases and the corresponding bearing diameter should be larger. Overall, the bearing diameters under different seismic design intensities and the same structural height were similar, indicating that the seismic isolation design is co-guided by the physical performance and design rules.

Table 2 Physical performance of seismic isolation designs under different design conditions

|

Design conditions |

Integrated physical performance ( |

Seismic reduction factor (汕reduce) |

Normalized surface pressure index (ppress) |

Normalized maximum bearing deformation index ( |

Normalized maximum inter-story drift ratio index ( |

|

|

7.5 degree, 30m |

Mean |

1.36 |

0.38 |

0.72 |

0.23 |

0.23 |

|

Std |

0.27 |

0.08 |

0.18 |

0.08 |

0.12 |

|

|

7.5 degree, 50m |

Mean |

1.19 |

0.39 |

1.00 |

0.27 |

0.38 |

|

Std |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

0.08 |

|

|

8 degree, 30m |

Mean |

1.32 |

0.40 |

0.59 |

0.30 |

0.33 |

|

Std |

0.30 |

0.09 |

0.17 |

0.10 |

0.17 |

|

|

8 degree, 50m |

Mean |

1.24 |

0.40 |

0.88 |

0.35 |

0.46 |

|

Std |

0.15 |

0.04 |

0.15 |

0.07 |

0.10 |

Mean denotes the average value, and Std denotes standard deviation.

Figure 12 Typical design results under different seismic isolation design conditions (the design drawing scales are the same), and LRB and NRB denote a lead rubber bearing and natural rubber bearing, respectively. The number accompanying the LRB and NRB is the diameter of the bearing. (a) 7.5 degree, 30 m. (b) 7.5 degree, 50 m. (c) 8 degree, 30 m. (d) 8 degree, 50 m

The case studies under different seismic isolation design conditions show that the designs by StructGAN-Hybrid can be adopted as the scheme design for the seismic isolation of shear wall structures. However, more detailed performance needs to be examined using refined model-based analysis.

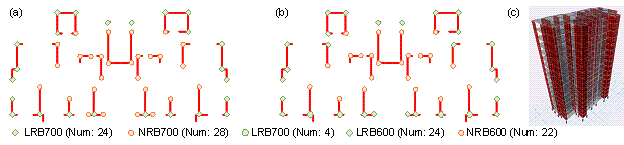

6.2 Typical case study based on refined model

The seismic isolation design and corresponding structural performance are further analyzed based on a typical refined structural model. In this case, the structural height is 48 m, story height is 3 m, planar size is 36.6 m ℅ 18.4 m, height每width ratio is 2.6, seismic design intensity is 8 degree, and characteristic period of the site is 0.4 s. The plan layouts of the shear wall structure and seismic isolation bearings are shown in Figure 13(a), where 24 LRB700 and 28 NRB700 seismic isolation bearings are used. In addition, this study invites engineers to undertake the seismic isolation design scheme illustrated in Figure 13(b) as a comparison case, where 4 LRB700, 24 LRB600, and 22 NRB600 seismic isolation bearings are employed in the design. The plan views of the comparison cases reveal that the intelligent and engineer designs are pretty similar.

Subsequently, the corresponding ETABS models are then established, and a representative model is shown in Figure 13(c). In the ETABS models, the equivalent linearization method of Equations (8) and (9) is used to derive the equivalent stiffness and damping of the LRB model in the response spectrum analysis; furthermore, in the time-history analysis, the mechanical model of lead rubber bearings (LRB) uses a bilinear model, and the mechanical model of natural rubber bearings (NRB) is linear. For readers who need more information about this case study, the ETABS models by StructGAN-Hybrid and engineer can be found at https://github.com/wenjie-liao/StructGAN-Hybrid.

Figure 13 Typical case of seismic isolation scheme design. (a) Plan view of seismic isolation design by StructGAN-Hybrid. (b) Plan view of seismic isolation design by engineer. (c) ETABS model of seismic isolation design.

Based on the ETABS model, modal analysis, static analysis under gravity load, and seismic performance analysis using the response spectrum and time-history analysis methods were performed. The analysis results reveal that both the StructGAN-Hybrid and engineer*s seismic isolation designs meet the design specifications and are comparable. The analysis results are elaborated as follows.

(1) Analysis results of StructGAN-Hybrid design based on response spectrum method

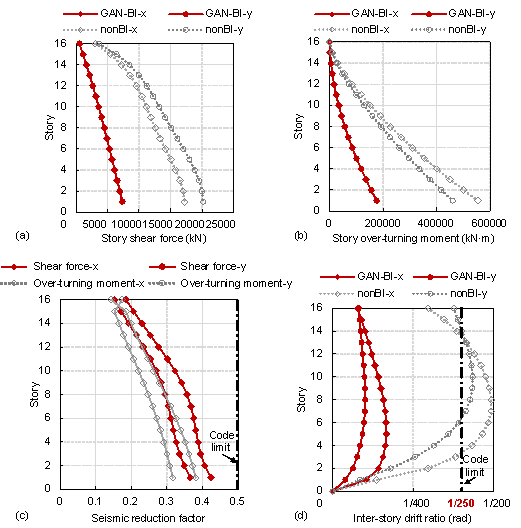

The dynamic characteristics of the structural model before and after the seismic isolation and the critical physical performance of the seismically isolated structure are listed in Table 3. The seismic dynamic response results based on response spectrum analysis are shown in Figure 14. The results indicate that the seismic isolation significantly reduces the seismic response and meets the specifications. Note that the engineer's design has been optimized to guarantee that it meets the specifications, and thus Table 3 and Figure 14 do not display the analysis results.

(a) Under the DBE, the corresponding story shear force and overturning moment are reduced. Based on a comparison of the story shear force and overturning moment before and after seismic isolation, the corresponding seismic reduction factor 汕reduce is obtained, which is 0.42 in this case (Figure 14) and meets the specification (i.e., < 0.5) [39].

(b) Under the MCE, the maximum deformation of the isolated bearing uBIh is 233 mm (Table 3), which is less than the code limit (i.e., 385 mm) [39], and the maximum inter-story drift ratio of the shear wall structure 牟drift is 1/599 (Figure 14), which is less than the code limit (i.e., 1/250) [39].

(c) Under the gravity load, the surface pressures of the seismic isolation bearings (shown in Table 3) meet the code requirements (i.e., < 15 MPa) [39], and under the gravity load and MCE, all of the bearings meet the code requirements (i.e., <30 MPa) [39].

Table 3 Structural dynamic characteristics and physical performance of seismic isolated structure

|

Structure |

Dynamic characteristics |

|||

|

1st order period (s) |

2nd order period (s) |

3rd order period (s) |

||

|

Shear wall structure |

1.212 |

0.985 |

0.779 |

|

|

Seismic isolated shear wall structure |

2.812 |

2.719 |

2.252 |

|

|

Difference |

132% |

176% |

189% |

|

|

Surface pressure under gravity load (MPa) |

Mean |

Maximum |

Code limit |

|

|

6.55 |

13.37 |

15 |

||

|

Surface pressure under gravity load and MCE (MPa) |

Mean |

Maximum |

Code limit |

|

|

12.48 |

21.66 |

30 |

||

|

Maximum bearing deformation (mm) |

Maximum |

Code limit |

||

|

233 |

385 |

|||

|

Design efficiency |

Competent engineer |

StructGAN-Hybrid |

Improvement |

|

|

30 minutes |

30 seconds |

60 times |

||

Figure 14 Physical performance of typical seismic isolated shear wall structure (excluding seismic isolation story). (a) Story shear force under DBE. (b) Overturning moment under DBE. (c) Seismic reduction factor. (d) Inter-story drift ratio under MCE.

(2) Seismic performance of intelligent and engineer designs based on time history analysis

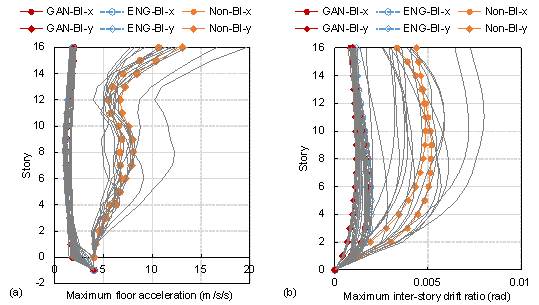

Subsequently, the seismic performance of the structures before and after seismic isolation are compared using the time-history analysis. Seven groups of ground motions (including horizontal and vertical directions) are selected from the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER) ground motion database [51], according to the selection specifications in the Chinese code [47]. Similar to the results of the response spectrum-based dynamic analysis, the maximum surface pressure and horizontal deformation of the isolation bearing and maximum inter-story drift ratio of the shear wall structure meet the code requirements. The inter-story drift ratio and floor acceleration envelopes of the structure under the MCE are shown in Figure 15. After seismic isolation, the maximum floor acceleration and inter-story drift ratio of the shear wall structure are significantly reduced. Specifically, the maximum floor acceleration and inter-story drift ratio of the isolated structure are approximately 20% and 30% of those without seismic isolation, respectively. In addition, the seismic performance of the intelligent design is comparable to that of the engineer*s design, showing that intelligent design can serve as a useful reference for engineers conducting subsequent optimization.

Figure 15 Seismic isolated structural performance of time-history analysis. The lines with labels GAN-BI, ENG-BI, and Non-BI are the average value of mechanics response of StructGAN-Hybrid design base isolation, engineer design base isolation, and design without isolation, respectively. (a) Comparison of maximum floor acceleration (story 0 denotes the isolation story, and story -1 denotes the foundation). (b) Comparison of inter-story drift ratio (without the isolation story deformation)

The case study shows that the StructGAN-Hybrid-generated design can meet the code requirements and effectively improve seismic performance. Furthermore, StructGAN-Hybrid can complete the scheme design of seismic isolation within 30 s and 60 times faster than engineers. The generated seismic isolation design can provide an effective initial reference for design optimization.

7. Conclusions

This study proposes a physics-rule-co-guided self-supervised GAN and the corresponding intelligent design method (StructGAN-Hybrid) for the seismic isolation design of a shear wall structure in the scheme design phase. StructGAN-Hybrid masters the seismic isolation design ability based on unsupervised learning, which can generate the layout and parameters of seismic isolation bearings by inputting the layout drawings of shear walls. The StructGAN-Hybrid-based design process is efficient, and the corresponding design can satisfy the design rules and code specifications. The detailed conclusions are as follows:

(1) The proposed physics-rule-co-guided self-supervised GAN consists of a generator, discriminator, physics estimator, and design rule evaluator. In the absence of ground-truth label data, pseudo-labels are created for the initial training phase, and the physics estimator and rule evaluator are used for the subsequent phase of generator optimization, which help to complete the self-supervised learning and design seismic isolation bearing parameters.

(2) The physics estimator is a deep neural network-based surrogate model, and the rule evaluator is a rule-based tensor operator. Therefore, the physics loss (output by the physics estimator) and rule loss (output by the rule evaluator) can effectively guide the backpropagation of the gradients and optimization of the generator parameters.

(3) The case studies validate that StructGAN-Hybrid can generate a well-performed scheme design that satisfies the empirical rules and critical code specifications. Under different seismic isolation design conditions, StructGAN-Hybrid can effectively generate different scheme designs that meet the corresponding requirements, and the design by StructGAN-Hybrid effectively reduces the structural dynamic response and improves the structural performance. Furthermore, the design efficiency can be improved approximately 60 times compared to the conventional engineer's design.

Currently, however, it is challenging for StructGAN-Hybrid to design complex structures (e.g., with irregular vertical or planar layouts and large height每width ratios). Uncertainty in load conditions, material properties, and load combinations cannot be thoroughly accounted for by the physics analysis model. In future studies, more adaptive physics and rule estimators will be developed.

Acknowledgments

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Moreover, the ETABS model of the typical design (shown in Figure 13) is available on GitHub (https://github.com/wenjie-liao/StructGAN-Hybrid).

REFERENCES

[1] Almufti I, Willford M. The REDi™ rating system: Resilience-based earthquake design initiative for the next generation of buildings. Arup 2013; 1-68.

[2] Dong Y, Frangopol DM. Performance-based seismic assessment of conventional and base-isolated steel buildings including environmental impact and resilience. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2016; 45(5): 739每756. DOI: 10.1002/EQE.2682.

[3] Fulin Z, Ping T. Recent progress and application on seismic isolation energy dissipation and control for structures in China. Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration 2018; 17(1): 19每27. DOI: 10.1007/S11803-018-0422-4.

[4] Fang DP, Li QW, Li N, Wang F, Liu Y, Gu DL, Sun CJ, Pan SJ, Hou GJ, Wang F, Lu XZ. An evaluation system for community seismic resilience and its application in a typical community. Engineering Mechanics, 2020, 37(10): 28每44. (in Chinese)

[5] Yin CY, Xie LL, Li AQ, Zeng DM, Yang CT, Wang XY. Comparison of the seismic-resilient design of seismically isolated reinforced concrete frame structures using two codes. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings 2021; 30(14): e1886. DOI: 10.1002/TAL.1886.

[6] Xie LL, Wang XY, Zeng DM, Jia J, Liu Q. Resilience-based retrofitting of adjacent reinforced concrete frame每shear wall buildings integrated into a common isolation system. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities 2021; 36(1): 04021100. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0001678.

[7] Wang XY, Xie LL, Zeng DM, Yang CT, Liu Q. Seismic retrofitting of reinforced concrete frame-shear wall buildings using seismic isolation for resilient performance. Structures 2021; 34: 4745每4757. DOI: 10.1016/J.ISTRUC.2021.10.081.

[8] Rakicevic Z, Bogdanovic A, Noroozinejad Farsangi E, Sivandi-Pour A. A hybrid seismic isolation system toward more resilient structures: Shaking table experiment and fragility analysis. Journal of Building Engineering 2021; 38: 102194. DOI: 10.1016/J.JOBE.2021.102194.

[9] Pan P, Zamfirescu D, Nakashima M, Nakayasu N, Kashiwa H. Base-isolation design practice in japan: Introduction to the post-Kobe approach. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2005; 9(1): 147每171. DOI: 10.1080/13632460509350537.

[10] Kelly JM. The role of damping in seismic isolation. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 1999; 28(1), 3每20. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9845(199901)

[11] Xue YT, Chang ZZ, Gao J. Guideline for seismic isolation design of building. Beijing, China Architecture & Building Press, 2016. (in Chinese)

[12] The State Council of China. Regulations on anti-seismic management of construction projects, 2021. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-08/04/content_5629341.htm (in Chinese)

[14] Liao WJ, Lu XZ, Huang YL, Zheng Z, Lin YQ. Automated structural design of shear wall residential buildings using generative adversarial networks. Automation in Construction 2021; 132: 103931. DOI: 10.1016/J.AUTCON.2021.103931.

[15] Liao WJ, Huang YL, Zheng Z, Lu XZ. Intelligent generative structural design method for shear wall building based on ※fused-text-image-to-image§ generative adversarial networks. Expert Systems with Applications 2022; 210, 118530. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118530

[16] Lu XZ, Liao WJ, Zhang Y, Huang YL. Intelligent structural design of shear wall residence using physics-enhanced generative adversarial networks. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2022; 51(7): 1657每1676. DOI: 10.1002/EQE.3632.

[17] Fei YF, Liao WJ, Huang YL, Lu XZ. Knowledge-enhanced generative adversarial networks for schematic design of framed tube structures. Automation in Construction 2022; 144, 104619. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104619

[18] Fei YF, Liao WJ, Zhang S, Yin PF, Han B, Zhao PJ, Chen XY, Lu XZ. Integrated schematic design method for shear wall structures: A practical application of generative adversarial networks. Buildings 2022; 12(9), 1295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12091295

[19] Zhao PJ, Liao WJ, Xue HJ, Lu XZ. Intelligent design method for beam and slab of shear wall structure based on deep learning. Journal of Building Engineering 2022; 57, 104838. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104838

[20] Zhao PJ, Liao WJ, Huang YL, Lu XZ. Intelligent design of shear wall layout based on attention-enhanced generative adversarial network. Engineering Structures 2023; 274, 115170. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115170

[21] Zhao PJ, Liao WJ, Huang YL, Lu XZ. Intelligent beam layout design for frame structure based on graph neural networks. Journal of Building Engineering 2023; 63, 105499. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105499

[22] Pizarro PN, Massone LM, Rojas FR, Ruiz RO. Use of convolutional networks in the conceptual structural design of shear wall buildings layout. Engineering Structures 2021; 239: 112311. DOI: 10.1016/J.ENGSTRUCT.2021.112311.

[23] Pizarro PN, Massone LM. Structural design of reinforced concrete buildings based on deep neural networks. Engineering Structures 2021; 241: 112377. DOI: 10.1016/J.ENGSTRUCT.2021.112377.

[24] Pizarro PN, Hitschfeld N, Sipiran I, Saavedra JM. Automatic floor plan analysis and recognition. Automation in Construction 2022; 140, 104348. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104348

[25] Fu B, Gao Y, Wang W. Dual generative adversarial networks for automated component layout design of steel frame-brace structures. Automation in Construction 2023; 146, 104661. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104661

[27] Zhu S, Ohsaki M, Hayashi K, Guo X. Machine-specified ground structures for topology optimization of binary trusses using graph embedding policy network. Advances in Engineering Software 2021; 159, 103032. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2021.103032

[28] Jeong JH, Jo H. Deep reinforcement learning for automated design of reinforced concrete structures. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2021; 36(12), 1508-1529. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/mice.12773

[29] Zou XK, Wang Q, Li G, Chan CM. Integrated reliability-based seismic drift design optimization of base-isolated concrete buildings. Journal of Structural Engineering 2010; 136(10): 1282每1295. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0000216.

[30] Çerçevik AE, Avşar Ö, Hasançebi O. Optimum design of seismic isolation systems using metaheuristic search methods. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2020; 131: 106012. DOI: 10.1016/J.SOILDYN.2019.106012.

[31] Peng Y, Ma Y, Huang T, De Domenico D. Reliability-based design optimization of adaptive sliding base isolation system for improving seismic performance of structures. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021; 205: 107167. DOI: 10.1016/J.RESS.2020.107167.

[32] Lu XZ, Liao WJ, Huang W, Xu YJ, Chen XY. An improved linear quadratic regulator control method through convolutional neural network每based vibration identification. Journal of Vibration and Control 2020; 27(7每8): 839每853. DOI: 10.1177/1077546320933756.

[33] Xu J, Design guide for engineering vibration isolation. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2021 (in Chinese)

[34] Zhang Y, Mueller C. Shear wall layout optimization for conceptual design of tall buildings. Engineering Structures 2017; 140: 225每240. DOI: 10.1016/J.ENGSTRUCT.2017.02.059.

[35] Lu XZ, Li MK, Guan H, Lu X, Ye LP. A comparative case study on seismic design of tall RC frame-core-tube structures in China and USA. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings 2015; 24(9): 687每702. DOI: 10.1002/TAL.1206.

[36] Tian Y, Lu X, Lu XZ, Li MK, Guan H. Quantifying the seismic resilience of two tall buildings designed using Chinese and US Codes. Earthquakes and Structures 2016; 11(6): 925每942. DOI: 10.12989/EAS.2016.11.6.925.

[37] Lu XZ, Zhang C, Liao WJ, Lin YQ, Lin XC, Xue HJ. Comparison of seismic performance between typical structural steel buildings designed following the Chinese and United States codes. Advances in Structural Engineering 2021; 24(9): 1828每1846. DOI: 10.1177/1369433220986633.

[38] Wang TC, Liu MY, Zhu JY, Tao A, Kautz J, Catanzaro B. High-resolution image synthesis and semantic manipulation with conditional GANs. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2018: 8798每8807. DOI: 10.1109/CVPR.2018.00917.

[39] GB/T 51408-2021. Standard for seismic isolation design of building. Beijing: China Planning Press, 2021. (in Chinese)

[40] Ma CF, Zhang YH, Tan P, Zhou FL. Seismic response of base-isolated high-rise buildings under fully nonstationary excitation. Shock and Vibration 2014; 2014. DOI: 10.1155/2014/401469.

[41] Miranda E, Asce M, Taghavi S. Approximate floor acceleration demands in multistory buildings. I: Formulation. Journal of Structural Engineering 2005; 131(2): 203每211. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9445(2005)131:2(203).

[42] Xiong C, Lu XZ, Guan H, Xu Z. A nonlinear computational model for regional seismic simulation of tall buildings. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 2016; 14(4): 1047每1069. DOI: 10.1007/S10518-016-9880-0/FIGURES/15.

[43] Lu XZ, McKenna F, Cheng QL, Xu Z, Zeng X, Mahin SA. An open-source framework for regional earthquake loss estimation using the city-scale nonlinear time history analysis: Https://DoiOrg/101177/8755293019891724 2020; 36(2): 806每831. DOI: 10.1177/8755293019891724.

[44] Xiong C, Huang J, Lu XZ. Framework for city-scale building seismic resilience simulation and repair scheduling with labor constraints driven by time每history analysis. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2020; 35(4): 322每341. DOI: 10.1111/MICE.12496.

[45] Zhou XY, Yu RF. CCQC method for seismic response of non-classically damped linear system based on code response spectra. Engineering Mechanics, 2006(02): 10每17+9. (in Chinese)

[46] Zhou XY, Yu RF, Dong D. Complex mode superposition algorithm for seismic responses of non-classically damped linear MDOF system. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2008; 8(4): 597每641. DOI: 10.1080/13632460409350503.

[47] GB 50011-2010. Code for seismic design of buildings. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2016. (in Chinese)

[48] Pytorch, 2022: https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/index.html.

[49] He KM, Zhang XY, Ren SQ, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2016; 2016-December: 770每778. DOI: 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

[50] He KM, Zhang XY, Ren SQ, Sun J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2016; 9908 LNCS: 630每645. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-46493-0_38/TABLES/5.

[51] Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER). PEER Ground Motion Database. https://ngawest2.berkeley.edu/