1 Introduction

Expensive optimization problems (EOPs) are prevalent in the engineering domain, characterized by high computational costs required to derive the objective functions or constraints of optimization problems, such as conducting large-scale, detailed numerical simulations (He et al., 2023) . Evolutionary algorithms (EAs), widely applied to resolve EOPs, necessitate fitness evaluations of numerous candidate solutions during the search for an optimal solution, often incurring prohibitive costs (J.-Y. Li et al., 2022) . To address this issue, surrogate-assisted evolutionary algorithms (SAEAs) have been developed recently (G. Li & Zhang, 2021; Wei et al., 2021, 2023; Xie et al., 2023) . By employing surrogate models to substitute for detailed numerical simulations during the evolutionary optimization process, the SAEAs effectively reduce the costs of optimization (Y. Jin et al., 2019; Negrin et al., 2023) .

In the field of structural engineering, the optimization design of reinforced concrete (RC) shear-wall structures represents a classic EOP. Shear-wall structures, typically composed of shear walls, beams, and slabs, are extensively utilized in RC high-rise residential buildings in earthquake-prone areas. Engineers usually define several design variables based on actual situations, with each set of design variables corresponding to a candidate solution of the optimization problem and its associated fitness. During the schematic design phase of a shear-wall structure, engineers are tasked with finalizing design proposals within a matter of days. Within this period, structural engineers must complete all structural designs corresponding to multiple candidate architectural designs, and ensure that the structural designs meet physical and economic requirements through optimization, thereby placing stringent demands on the efficiency of the design optimization process.

In traditional optimization design of shear-wall structures, it is necessary to establish detailed physical models of each structural member within a chosen finite element software to analyze their physical responses under various working conditions such as gravity loads and earthquakes (Y. Li et al., 2011; X. Lu et al., 2013, 2015) . This is followed by conducting a detailed reinforcement design to ascertain material usage (Men et al., 2014) . For a typical shear-wall structure, this evaluation process can take approximately 5 min for a single candidate solution. Although EAs have proven to be highly effective in the optimization design of shear-wall structures (Gan et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2022; F. Jin et al., 2023) , they often require hundreds of fitness evaluations to reach an acceptable local optimum. Consequently, the time taken for optimization design of shear-wall structures depends completely on detailed physical models; the use of EAs is prohibitively expensive and potentially impractical in circumstances such as the schematic design phase where a quick turnaround is desirable. To address the challenges mentioned above, SAEAs have been employed to reduce the optimization costs of RC shear-wall structures and other high-rise building structures. For instance, Lou et al. (2021) developed a data-driven tabu search algorithm that employed a support vector machine to evaluate the fitness of shear-wall structures. Huang et al. (2023) introduced a surrogate-assisted genetic algorithm that used a radial basis neural network during the optimization process to evaluate the natural periods of framed-tube structures. Similarly, Alanani & Elshaer (2023) presented an artificial neural network-assisted genetic algorithm for the layout design of shear walls in high-rise buildings. Z. Wang et al. (2023) proposed an optimization method based on surrogate model updating that utilized a generalized regression neural network to substitute for wind tunnel experiments and simulations during the design process of super-tall buildings.

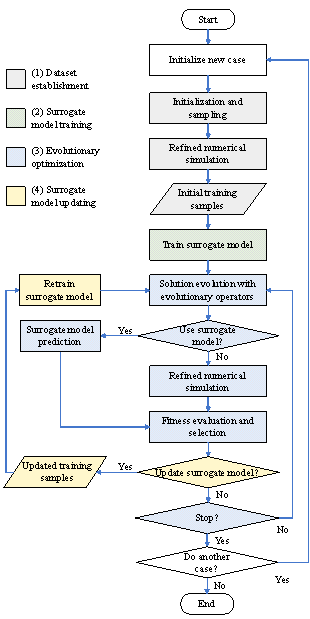

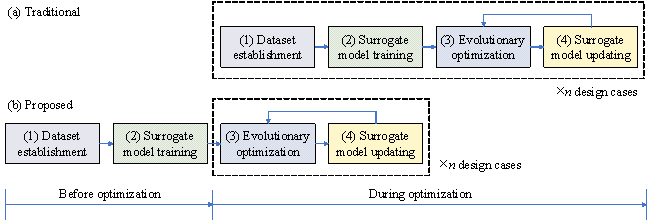

Figure 1 Framework of traditional and proposed SAEAs

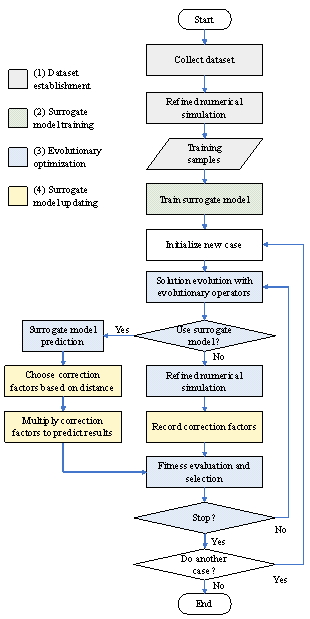

The typical framework and workflow of the SAEAs mentioned above, as presented in Figures 1(a) and 2, respectively, include four main parts: (1) Dataset establishment: Initialize and sample within the design space; perform numerical simulations on the samples to acquire evaluation results, which are then used as training samples. (2) Surrogate model training: Use design variables as inputs and the evaluation results as outputs; establish a machine-learning surrogate model based on the training samples. (3) Evolutionary optimization: Perform optimization based on evolutionary operators, employing either the surrogate model or a refined method for fitness evaluation. (4) Surrogate model updating: Add the design variables and the corresponding evaluation results by refined methods to the training samples, and retrain the surrogate model.

|

|

|

|

Figure 2 Workflow of the traditional SAEA |

Figure 3 Workflow of the proposed SAEA (GAEA) |

Note that, the input to the surrogate model (i.e., design variables) in part (2) is case-specific, meaning that the trained surrogate model only applies to that particular case during optimization. A new case necessitates re-execution of parts (1) and (2) to build a new dataset and train a new surrogate model. This limitation indicates that the existing SAEAs provide only a marginal increase in optimization efficiency compared to the EAs and may not fully meet the requirement of rapid optimization in the schematic design phase. For example, the SAEAs proposed by Lou et al. (2021) and Huang et al. (2023) have led to a saving in computational time by only 30% and 26%, respectively, compared to EAs without using surrogate models. Hence, there is an urgent need for an SAEA based on a generalizable surrogate model that, once trained, can be applied across a variety of structure cases (e.g., different shear-wall structures) without the need for retraining. This would significantly enhance the time efficiency of the existing SAEA, enabling it to meet the demands for fast optimization tasks during the schematic design phase.

The move towards a generalizable surrogate model indeed sets a higher bar for the model construction approach. Traditional machine learning methods used in current SAEA research efforts, such as Kriging, support vector machines, and artificial neural networks, are mostly designed to cater for specific cases (Negrin et al., 2023) . The limitations of these methods have been recognized for their typically single input form (vector) and the smaller number of trainable parameters, which hinders their ability to construct a generalizable representation suitable for laborious structural design tasks and to offer powerful nonlinear mapping capabilities required for predicting a diverse range of cases. Deep learning methods, which have risen to prominence recently, differ from traditional machine learning methods by allowing for diverse forms of input (such as images and graphs) and a large number of trainable parameters, rendering them wider applicability and better generalization capabilities. Graph neural networks (GNNs) represent a class of deep learning models based on graph representations, better suited for building structure design-related tasks (Chang & Cheng, 2020; Hayashi & Ohsaki, 2022; Zhao, Liao, et al., 2023) . The authors have laid a foundation for this study by proposing GNN-based surrogate models that can predict both physical responses and material usages of RC shear-wall structures (Fei et al., 2023, 2024) . After training on hundreds of shear-wall structures, these GNN surrogate models have shown promising generalizability to new structure cases. Despite these advances, the lengthy training time for GNN exceeds that of traditional machine learning models, making the conventional model updating approach of retraining (depicted in Figure 2) unsuitable. Therefore, this study is aimed at delving into how can GNNs be efficiently combined with EAs. A critical aspect of this study will be to find efficient ways to update the GNN without the necessity of retraining from scratch.

In response to the challenges mentioned above, this study presents a GNN-assisted EA that realizes rapid optimization design of shear-wall structures, with no need to rebuild the dataset and retrain the surrogate model when applied to new structure cases. The core innovations include the novel framework and workflow of GAEA, the generalizable GNN surrogate model, and the efficient updating strategy for the surrogate model. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the framework of the proposed method and its data foundation. Section 3 formulates the shear-wall structure design task as an optimization problem. Section 4 introduces the GNN-based surrogate model. Section 5 proposes a distance-based surrogate model evaluation and updating strategy. Section 6 presents several typical case studies. Section 7 provides the major conclusions of this study.

2 Framework and dataset of GAEA

2.1 Framework

This study aims to propose a novel SAEA framework, referred to as the GNN-assisted evolutionary algorithm (GAEA). For a new case of a given structural system, such as a shear-wall structure, GAEA can establish a generalizable surrogate model in advance, which can be directly used for fitness evaluation without the need to reconstruct the dataset and retrain the surrogate model like traditional SAEAs.

The framework of the proposed GAEA is shown in Figure 1(b), and its workflow is presented in Figure 3. The proposed GAEA also consists of four parts: (1) Dataset establishment (Section 2.2): Collect hundreds of design cases of the targeted structural system, conduct detailed numerical simulations, obtain evaluation results, and use them as a dataset. (2) Surrogate model training (Section 4): Employ a universal representation method, using design information as input and evaluation results as output. Train a generalizable GNN-based surrogate model using the dataset. (3) Evolutionary optimization (Sections 3 & 5): Perform optimization based on evolutionary operators, convert design variables into design information, and perform fitness evaluations using the surrogate model or a refined method. (4) Surrogate model updating (Section 5): Multiply an error correction factor, which is chosen based on the distance between design variables, to the predictions of the surrogate model. The surrogate model is updated by adjusting the error correction factor, rather than retraining.

The major innovations and advantages of the proposed GAEA are: parts (1) and (2) can be completed in advance during leisure time prior to the optimization process. Once a design task is assigned and optimization is required to be completed in a timely manner, GAEA can employ the GNN-based surrogate model that has been pre-trained to accelerate the optimization design. In addition, when multiple structure cases are to be optimized, only parts (3) and (4) are required to be repeated. On the contrary, when using traditional SAEAs to optimize multiple cases, all four parts shown in Figure 2, including parts (1) and (2), must be repeatedly executed. Therefore, for practical engineering applications, the efficiency of GAEA is expected to be significantly higher than that of the traditional SAEAs.

Based on a survey of experienced structural engineers, the following three timing scenarios for optimization design can be well integrated with engineers' workflow during the schematic design phase:

(1) 10-minute optimization: Engineers can check optimization results after their 10-minute tea break.

(2) 45-minute optimization: 45 minutes is the longest time that engineers are willing to wait during their normal design pace.

(3) 120-minute optimization: Engineers can check the optimization results after their 120-minute lunch break.

In the following sections, the optimization design of RC shear-wall structures is taken as an example to verify the effectiveness of the proposed GAEA for the aforementioned three optimization timing scenarios.

2.2 Dataset for GNN training

To train a generalizable GNN surrogate model, it is necessary

to collect as many design cases of the targeted structural system as possible.

A total of 283 design drawings of RC shear-wall structures are collected from

several renowned design institutes in China, from which the structural design

and design conditions of the shear-wall structures are extracted. Structural

design includes the layout and geometric dimensions of the shear walls and

beams. Key design conditions consist of seismic, site, and height conditions,

which are characterized by the design seismic acceleration ( ![]() ), site characteristic period (

), site characteristic period ( ![]() ), and the number of stories (

), and the number of stories ( ![]() ), respectively (Zhao, Fei, et al., 2023) . To enhance the diversity of the dataset and in turn improve the generalization

capability of the GNN surrogate model, data augmentation is employed. Synthetic

cases are generated by randomly changing the layout of the shear walls and

beams or the design conditions based on real-world cases (Fei et al., 2024) . The dataset is expanded

to four times its original size, resulting in a total of 1132 shear-wall structure

cases.

), respectively (Zhao, Fei, et al., 2023) . To enhance the diversity of the dataset and in turn improve the generalization

capability of the GNN surrogate model, data augmentation is employed. Synthetic

cases are generated by randomly changing the layout of the shear walls and

beams or the design conditions based on real-world cases (Fei et al., 2024) . The dataset is expanded

to four times its original size, resulting in a total of 1132 shear-wall structure

cases.

For each shear-wall structure case in the dataset, parametric

modeling is used to establish its finite element (FE) model for structural

analysis and reinforcement design (Fei et al., 2022) , thereby obtaining the

physical responses (inter-story drift ratio ![]() , torsional period ratio

, torsional period ratio ![]() , shear-weight ratio

, shear-weight ratio ![]() , and axial compression ratio

, and axial compression ratio ![]() ) and material usages (concrete volume

) and material usages (concrete volume ![]() and reinforcement mass

and reinforcement mass ![]() ) required for fitness evaluation, as detailed in Section 3.2. Seventy

or so cases that significantly deviate from the regulations of Chinese design

codes are removed from the dataset, resulting in 1056 shear-wall structure

cases.

) required for fitness evaluation, as detailed in Section 3.2. Seventy

or so cases that significantly deviate from the regulations of Chinese design

codes are removed from the dataset, resulting in 1056 shear-wall structure

cases.

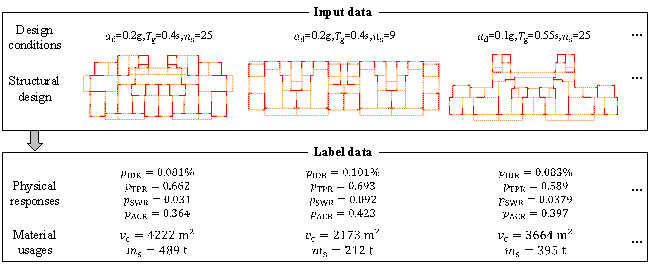

Figure 4 Examples of the established shear-wall structure dataset

Finally, examples of the established dataset for shear-wall structures are presented in Figure 4. The input data are structural design and design conditions, while the label data (ground truth) are the physical responses and material usages. It should be noted that among these training data, some completely conform to the design codes, while others do not entirely comply; however, both types of data are crucial for the subsequent surrogate model training. This is because the structural designs at the early phases of optimization are often not code-conforming, while those at the later phases usually are. These two types of training data help the surrogate model to better adapt to the entire optimization process.

2.3 Typical cases for GAEA validation

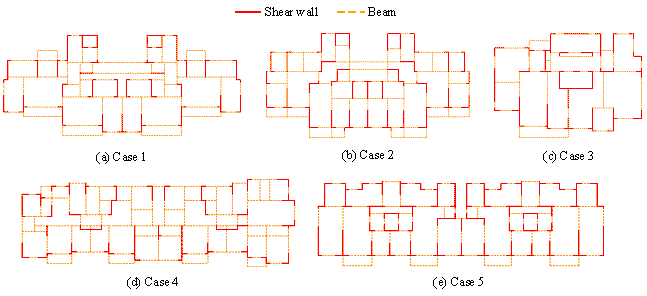

Figure 5 Initial structural layouts of typical shear-wall structures

Five typical shear-wall structure cases are selected for the GAEA validation. Their initial structural layouts (as shown in Figure 5) and design conditions (as presented in Table 1) are common and diversified. To verify the proposed GAEA, numerical experiments are carried out in Sections 4 & 5 based on the five shear-wall structure cases. The specific optimization results for three of the cases are provided in Section 6.

Table 1 Design conditions of typical shear-wall structures

|

Case ID |

|

|

|

Concrete grade |

Rebar grade |

|

1 |

0.1 |

0.45 |

24 |

C30~C40 |

HRB400 |

|

2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

26 |

C30~C45 |

HRB400 |

|

3 |

0.2 |

0.45 |

27 |

C30~C45 |

HRB400 |

|

4 |

0.1 |

0.55 |

19 |

C30~C35 |

HRB400 |

|

5 |

0.3 |

0.55 |

11 |

C30~C40 |

HRB400 |

Note:

![]() is design seismic acceleration;

is design seismic acceleration; ![]() is site period;

is site period; ![]() is number of stories; C30, C35, C40, C45 stand for standard

cubic compressive strengths of 30, 35, 40, 45 MPa, respectively; HRB400 stands

for standard yield strength of 400 MPa.

is number of stories; C30, C35, C40, C45 stand for standard

cubic compressive strengths of 30, 35, 40, 45 MPa, respectively; HRB400 stands

for standard yield strength of 400 MPa.

3 Optimization problem of shear-wall structural design

The design of shear-wall structures is based on architectural design, and the layout of structural components must not affect the architectural space. The structural design includes three phases, namely schematic design, detailed design, and construction drawing design, with the first phase being the focus of this study. Specifically, in the schematic design phase, an initial design is typically carried out by experienced structural engineers or trained deep-learning models (Liao et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2023) . Initial design usually includes the planar layout, section dimensions, and material grades of shear walls and beams, etc. Based on the initial design, optimization design is performed to adjust the shear-wall structure so that material cost is minimized while meeting the architectural requirements of the contractors and the physical requirements of the design codes. Since the shear-wall length is a core factor affecting the physical and economic performance of shear-wall structures (Zhou et al., 2022) , this study focuses on the optimization of shear-wall lengths.

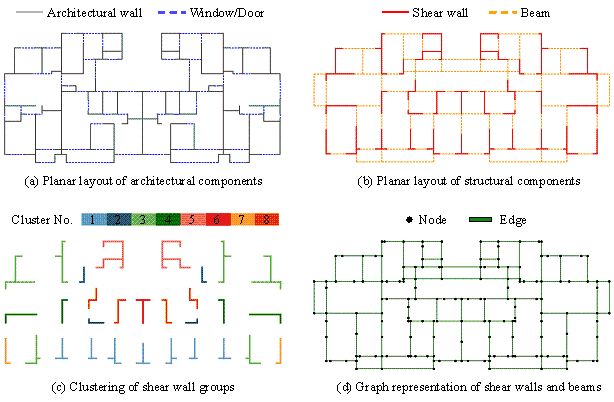

3.1 Design variables

A typical shear-wall structure is shown in Figure 6. The planar layout of architectural components in the architectural design is shown in Figure 6(a), where the shear walls can only be placed within the location of the architectural walls. The planar layout of structural components in structural design is shown in Figure 6(b), which usually includes dozens of shear walls. To reduce the number of design variables, thereby simplifying the optimization complexity, connected shear walls are defined as shear wall groups, and the K-means algorithm is used to cluster these shear wall groups (Qin et al., 2024) . The clustering is based on features such as the shape and location of the shear wall groups, as detailed in Table 2. According to Qin et al. (2024) , the number of clusters is chosen as eight. Using increased numbers of clusters, e.g., 16 and 32, has been found to have a minor impact on the optimization results. After clustering the shear walls in Figure 6(b) into eight groups, the resulting clusters are shown in Figure 6(c).

Figure 6 A typical shear-wall structure

Table 2 Features of shear wall groups for clustering (Qin et al., 2024)

|

Index |

Feature |

|

1 |

The number of nodes connected to only one edge |

|

2 |

The number of nodes connected to two edges |

|

3 |

The number of nodes connected to three edges |

|

4 |

Total length of wall groups |

|

5 |

The average distance from the x-coordinate of nodes to the center |

|

6 |

The average distance from the y-coordinate of nodes to the center |

Define a design variable vector ![]() , where the design variable

, where the design variable ![]() corresponds to the wall length of the i-th shear

wall cluster. Here,

corresponds to the wall length of the i-th shear

wall cluster. Here, ![]() is a floating-point number, ranging from

is a floating-point number, ranging from ![]() . The initial design corresponds to

. The initial design corresponds to ![]() . When

. When ![]() , all the wall lengths in the i-th shear wall cluster are considered

to have reduced by 100%. When

, all the wall lengths in the i-th shear wall cluster are considered

to have reduced by 100%. When ![]() , all the wall lengths in the i-th shear wall cluster are regarded

as having increased by 100%. When

, all the wall lengths in the i-th shear wall cluster are regarded

as having increased by 100%. When ![]() , all the wall lengths are altered proportionally in a similar manner.

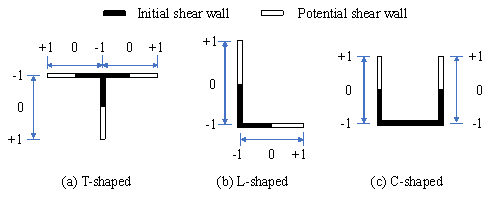

For common wall group shapes (T-shaped, L-shaped, C-shaped), the wall lengths

corresponding to different design variable values are shown in Figure 7. In

addition, the wall lengths are also subject to certain design rules: 1) the

layout of shear walls shall not exceed the position of the architectural walls,

to avoid affecting the building's functional space (as shown in Figure 6(a));

2) according to the Chinese design codes, the ratio of the wall length to

the wall thickness must not be less than 4 (MOHURD, 2010) .

, all the wall lengths are altered proportionally in a similar manner.

For common wall group shapes (T-shaped, L-shaped, C-shaped), the wall lengths

corresponding to different design variable values are shown in Figure 7. In

addition, the wall lengths are also subject to certain design rules: 1) the

layout of shear walls shall not exceed the position of the architectural walls,

to avoid affecting the building's functional space (as shown in Figure 6(a));

2) according to the Chinese design codes, the ratio of the wall length to

the wall thickness must not be less than 4 (MOHURD, 2010) .

When the shear wall lengths are changed, the beam lengths are adjusted accordingly without altering the topological relationship. The cross-sectional dimensions of the shear walls and beams are determined based on statistical rules (X. Lu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022) . Note that the material grades are consistent with the initial design.

Figure 7 Relationship between design variable values and shear wall lengths

3.2 Objective functions

After comprehensively considering various factors in shear wall design and referencing existing related works (Men et al., 2014; Lou et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022; F. Jin et al., 2023; Qin et al., 2024) , this study adopts the following objective functions.

(1) Define an objective function ![]() for the construction material quantity, which reflects the material cost of a shear-wall

structure, as shown in Equation (1):

for the construction material quantity, which reflects the material cost of a shear-wall

structure, as shown in Equation (1):

|

|

(1) |

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the unit prices of concrete and steel reinforcement,

respectively, determined according to the local market prices;

are the unit prices of concrete and steel reinforcement,

respectively, determined according to the local market prices; ![]() and

and ![]() are the concrete volume and steel reinforcement mass of

the structure, respectively.

are the concrete volume and steel reinforcement mass of

the structure, respectively.

(2) Define an objective function ![]() for the inter-story drift ratio of the structure, which

should not exceed the maximum limit specified by the design code, but also

shall not be unnecessarily small, as expressed in Equation (2):

for the inter-story drift ratio of the structure, which

should not exceed the maximum limit specified by the design code, but also

shall not be unnecessarily small, as expressed in Equation (2):

|

|

(2) |

where ![]() is the maximum inter-story drift ratio of the structure,

and

is the maximum inter-story drift ratio of the structure,

and ![]() is the maximum allowable inter-story drift ratio specified

by the design code.

is the maximum allowable inter-story drift ratio specified

by the design code.

(3) Define an objective function ![]() for the torsional period ratio of the structure, which

should not exceed the maximum limit specified by

the design code, and it shall be as small as possible, as shown in

Equation (3):

for the torsional period ratio of the structure, which

should not exceed the maximum limit specified by

the design code, and it shall be as small as possible, as shown in

Equation (3):

|

|

(3) |

where ![]() is the torsional period ratio of the structure, and

is the torsional period ratio of the structure, and ![]() is the maximum allowable torsional period ratio specified

by the design code.

is the maximum allowable torsional period ratio specified

by the design code.

(4) Define an objective function ![]() for the shear-weight ratio of the structure, which should

not be smaller than the minimum limit specified by the design code, as

shown in Equation (4):

for the shear-weight ratio of the structure, which should

not be smaller than the minimum limit specified by the design code, as

shown in Equation (4):

|

|

(4) |

where ![]() is the minimum shear-weight ratio of the structure, and

is the minimum shear-weight ratio of the structure, and

![]() is the minimum allowable shear-weight ratio specified by

the design code.

is the minimum allowable shear-weight ratio specified by

the design code.

(5) Define an objective function ![]() for the axial compression ratio. This ratio should not

exceed the maximum limit specified by the design

code, as shown in Equation (5):

for the axial compression ratio. This ratio should not

exceed the maximum limit specified by the design

code, as shown in Equation (5):

|

|

(5) |

where ![]() is the proportion of shear walls with

an excessive axial compression ratio,

is the proportion of shear walls with

an excessive axial compression ratio, ![]() is the axial compression ratio of the i-th shear

wall on the first story of the structure,

is the axial compression ratio of the i-th shear

wall on the first story of the structure, ![]() is the maximum allowable axial compression ratio of the

i-th shear wall, and

is the maximum allowable axial compression ratio of the

i-th shear wall, and ![]() is a function for counting the number of specified shear

walls.

is a function for counting the number of specified shear

walls.

(6) Finally, define a total objective function ![]() for transforming the multi-objective problem into a single

objective problem, as shown in Equation (6) (Qin et al., 2024) , which is to be minimized.

for transforming the multi-objective problem into a single

objective problem, as shown in Equation (6) (Qin et al., 2024) , which is to be minimized.

|

|

(6) |

Note that the maximum/minimum limits for physical responses are determined according to the local design codes (MOHURD, 2010) . In practical engineering projects, there is generally a safety redundancy in structural design. Therefore, the maximum or minimum limits specified by the design codes are increased or decreased by 10%, respectively, during the process of optimization.

Note also that the above definitions of the objective functions are

only a feasible solution for the targeted design task. If the objective functions

are defined for other tasks, the proposed GAEA can also be directly used to

accelerate the optimization process. For example, some of the objective functions,

e.g., ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , can be considered as constraint conditions, and a weighted

sum can be used to transform the multi-objective problem into a single-objective

one. The specific form of the objective functions and constraint conditions

does not influence the effectiveness of the proposed GAEA,

being a versatile optimization method.

, can be considered as constraint conditions, and a weighted

sum can be used to transform the multi-objective problem into a single-objective

one. The specific form of the objective functions and constraint conditions

does not influence the effectiveness of the proposed GAEA,

being a versatile optimization method.

In the optimization problem of this study, the fitness evaluation

requires two material usage indicators ( ![]() and

and ![]() ) and four physical response indicators (

) and four physical response indicators ( ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ). For refined evaluations, the above-mentioned indicators can be obtained

through parametric modeling and the FE models. For rapid evaluations, the

above-mentioned indicators can be predicted using the GNN surrogate model

described in Section 4.

). For refined evaluations, the above-mentioned indicators can be obtained

through parametric modeling and the FE models. For rapid evaluations, the

above-mentioned indicators can be predicted using the GNN surrogate model

described in Section 4.

4 GNN-based surrogate model

A generalizable surrogate model for the rapid optimization design of shear-wall structures must meet two key requirements. First, it must be able to comprehensively consider design information, especially the topological relationships between structural components, for accurate fitness evaluation. Second, once trained, it must be applicable to shear-wall structures of any scale, regardless of the number of structural components, so that a high evaluation efficiency can be ensured. Traditional machine learning methods cannot meet these requirements (as detailed discussed in Section 4.3), a GNN is therefore adopted in this study.

4.1 Graph neural networks

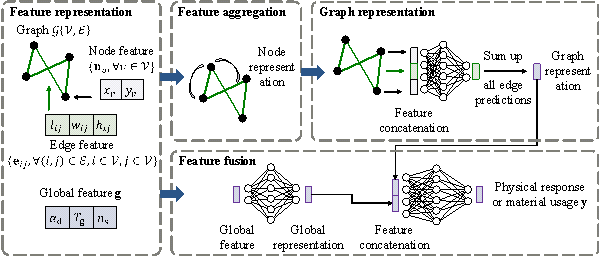

To evaluate the physical responses and material usages of shear-wall structures, it's necessary to consider the structural layout (topological information), component sizes (geometric information), and design conditions (textual information) simultaneously. To effectively integrate these heterogeneous input data, a GNN architecture recently proposed by the authors (Fei et al., 2023) , known as Graph-GEN, is used as the surrogate model. This method incorporates feature representation, feature aggregation, graph representation, and feature fusion algorithms specifically designed for tasks related to building structures, as depicted in Figure 8. Compared to traditional machine learning methods, Graph-GEN is a more generalizable surrogate model for the design of shear-wall structures.

Figure 8 Architecture of Graph-GEN

Table 3 Input and output variables of Graph-GEN

|

Variable |

Representation form |

|

|

Input |

Graph |

Node set |

|

Node features { |

|

|

|

Edge features { |

|

|

|

Global features |

|

|

|

Output |

Vector representations |

|

To construct a surrogate model applicable to various shear-wall structure cases, a universal feature representation method is crucial. For any shear-wall structure, all its design information can be represented as a graph and a vector. Specifically:

(1) The structural design of the shear-wall structure is represented as a graph, which is compatible with the input format of GNNs. First, intersections of shear walls and beams are represented as nodes, and the shear walls and beams themselves are represented as edges. For example, the graph in Figure 6(d) is used to represent the structural layout in Figure 6(b). Additionally, planar coordinates of the intersections are used as node features (2-dimensional vector), and the geometric dimensions of the structural components (length, width, height) are used as edge features (3-dimensional vector), as presented in Table 3.

(2) The design conditions also significantly affect the physical responses

and material usages of the shear-wall structure. Critical design conditions

(design seismic acceleration ![]() , site characteristic period

, site characteristic period

![]() , and number of stories

, and number of stories ![]() ) are represented as a global feature vector, as indicated

in Table 3.

) are represented as a global feature vector, as indicated

in Table 3.

4.2 Surrogate modeling

According to the characteristics of various physical responses and material usages, the following approaches are adopted to construct their surrogate models:

(1) Several end-to-end data-driven surrogate models

are established based on GNNs to predict the material usage (i.e., the concrete

volume ![]() and the steel reinforcement mass

and the steel reinforcement mass

![]() ), the first-order torsional period

), the first-order torsional period ![]() , and the story stiffness

, and the story stiffness ![]() (including flexural and shear stiffnesses in

X and Y directions). Prior knowledge has been incorporated into the loss function or output layer of the

GNNs to prevent the predicted material usage from falling below the minimum

values required by design codes (Fei et al., 2023)

and to avoid the prediction of negative values for physical quantities

that should be positive (Fei et al., 2024)

.

(including flexural and shear stiffnesses in

X and Y directions). Prior knowledge has been incorporated into the loss function or output layer of the

GNNs to prevent the predicted material usage from falling below the minimum

values required by design codes (Fei et al., 2023)

and to avoid the prediction of negative values for physical quantities

that should be positive (Fei et al., 2024)

.

(2) The axial compression ratio ![]() and the story mass

and the story mass ![]() are directly calculated based on the design rules and physical

principles.

are directly calculated based on the design rules and physical

principles.

(3) Based on the predicted story stiffness ![]() and the calculated story mass

and the calculated story mass ![]() , multi-degree-of-freedom flexural-shear models are established

(Fei et al., 2024) . By conducting modal analyses on these multi-degree-of-freedom

models, the first-order translational periods in the X and Y

directions (

, multi-degree-of-freedom flexural-shear models are established

(Fei et al., 2024) . By conducting modal analyses on these multi-degree-of-freedom

models, the first-order translational periods in the X and Y

directions ( ![]() and

and ![]() ) can be obtained, which are then used to calculate the torsional

period ratio

) can be obtained, which are then used to calculate the torsional

period ratio ![]() . Further, by performing response spectrum analyses, the story

displacements and shear forces under design-level earthquakes can be obtained,

which in turn yield the inter-story drift ratio

. Further, by performing response spectrum analyses, the story

displacements and shear forces under design-level earthquakes can be obtained,

which in turn yield the inter-story drift ratio ![]() and the shear-weight ratio

and the shear-weight ratio ![]() .

.

(4) It should be highlighted that three strategies have been implemented to enhance the generalization performance of the surrogate models. First, a large-scale and diversified training set is collected, and its scale and diversity are further improved through data augmentation techniques. Second, general prior knowledge has been incorporated into the surrogate models to avoid making fundamental errors. Third, the surrogate models integrate data-driven and physics-based methods, making them less of a black box. Our previous works have also demonstrated that the surrogate models achieve high prediction accuracy on the test set, which is separate from the training set (Fei et al., 2023, 2024) .

It is important to note that when applying the surrogate model for fitness evaluation, the case-specific design variables should be transformed into the universal design information (graph and vector) before being fed into the surrogate model for model prediction.

4.3 Comparison with other machine learning methods

Due to its unique feature representation method and model architecture, the GNN being adopted in this study is considered superior to traditional machine learning methods in performing building structural design tasks.

For the feature representation method, the design information of building structures can be represented as a graph and a vector with complete topological, geometric, and textual information without missing any data. These graphs and vectors will be directly operated by the GNN, facilitating full capture of complex relationships in structural design tasks. In contrast, when using traditional machine learning methods, e.g., Kriging, support vector machine, or multilayer perceptrons, the design information of building structures can only be represented as a vector, which potentially causes a loss of the topological relationships of structural components.

For the model architecture, the GNN operations are iteratively performed on each node, its neighbors, and the connected edges. Therefore, the trained GNN model can be applied to graphs of any size, i.e., building structures with any number of structural components, featuring an excellent generalization capability. On the other hand, when using traditional machine learning methods, the trained model can only handle the input vector of a fixed size, resulting in poor generalization capability.

In the authors* previous works (Fei et al., 2023, 2024) , the performances of the GNN and traditional machine learning methods (e.g., multilayer perceptrons) have been compared in detail. Our published experiment results indicate that the prediction accuracy of the GNN is significantly higher than traditional machine learning methods, thereby supporting the above statements.

Recently, novel machine learning techniques have garnered widespread attention in the fields of scientific computation and engineering simulation, with significant advancements including DeepONet (L. Lu et al., 2021) and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) (Raissi et al., 2019; Cuomo et al., 2022) . These methods can be utilized to learn to solve physical problems, particularly those involving partial differential equations (PDEs). However, in the context of the optimization design of shear-wall structures, the key challenge lies in determining structural properties (e.g., story stiffness) and material usages based on design information. This determination is not controlled by PDEs but is instead based on calculation assumptions, construction requirements, empirical formulas, and other specifications as dictated by design codes. With the structural properties predicted, one can further employ well-established physical models (e.g., flexural-shear models) to carry out physical response calculations (typically matrix computation and eigenvalue analysis), swiftly obtaining the necessary responses without the need for machine learning predictions. Therefore, surrogate models such as DeepONet and PINNs, which are designed to solve physical problems, are not applicable to the optimization design tasks of shear-wall structures. On the contrary, the proposed GNN-based surrogate models are tailored for the intended design task and are, therefore, more suitable.

4.4 Prediction accuracy and efficiency

Numerical experiments are conducted on a personal computer equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU and an Intel Core i7-10700K CPU @ 3.80GHz. The Graph-GEN described in Section 4.1 is implemented based on the PyTorch deep learning framework (PyTorch, 2024) and trained on the GPU. The creation and operation of graphs are performed using the Deep Graph Library (DGL, 2024) . The modeling and optimization of shear-wall structures described in Section 3 are implemented through secondary development in commercial structural design software YJK-GAMA (GAMA, 2023b) , which provides robust toolboxes for parametric modeling, FE modeling, and EA, and is widely used in the Chinese construction industry.

Based on the dataset described in Section 2.2, the GNN surrogate models are trained and validated using the same method as reported in the previous works of the authors (Fei et al., 2023, 2024) . The hyperparameters of the GNN models are also selected based on our previous numerical experiments. The trained GNN surrogate models are used to predict the physical responses and material usages of the five typical cases described in Section 2.3. The objective functions are calculated according to the equations described in Section 3.2. The FE model evaluations by YJK-GAMA are used as the ground truth. The maximum and minimum percentage errors (PE) of the five cases and the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) across the five cases are calculated. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 Objective function errors of typical cases evaluated by GNN surrogate models

|

Metrics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maximum PE |

16.9% |

1.2% |

16.0% |

6.0% |

3.3% |

17.6% |

|

Minimum PE |

-5.2% |

-13.2% |

-17.8% |

-5.7% |

-0.2% |

0.0% |

|

MAPE |

7.4% |

4.6% |

8.0% |

2.4% |

1.1% |

7.9% |

The results indicate that the MAPE of the total objective function is 7.4%, with the PE ranging from -5.2% to 16.9%. The MAPE for individual objective functions ranges from 1.1% to 8.0%, with the corresponding PE ranging from -17.8% to 17.6%. It is concluded that the GNN surrogate models are capable of performing an accurate fitness evaluation of shear-wall structures in most circumstances, but there are substantial errors in a few instances. Therefore, GAEA needs to employ the refined evaluation by the FE model to correct the rapid evaluation by the GNN surrogate models.

Within the environment of YJK-GAMA, a single fitness evaluation using the GNN surrogate models takes about 6 s, whereas using the FE model takes approximately 5 min. Hence, the evaluation efficiency of the GNN surrogate models is approximately 50 times that of the FE model.

5 Distance-based surrogate model evaluation and updating

5.1 Proposed strategy

For every new design variable vector generated during the optimization process, there are two different ways to conduct a fitness evaluation: (1) Rapid evaluation based on surrogate models: This involves quickly evaluating the design performance using GNN surrogate models, noting that surrogate models are an approximation of detailed numerical simulations and are inevitably prone to errors. (2) Refined evaluation based on FE models: This involves establishing a detailed FE model corresponding to the design variable vector to calculate its performance. The advantages and disadvantages of the refined evaluation are the exact opposite of rapid evaluation. The efficiency of refined evaluation is lower than that of rapid evaluation, but it has higher accuracy.

Combining the advantages of the above two methods, SAEA typically carries out both rapid and refined evaluations during the optimization process and uses the results of the refined evaluations to update the surrogate models, keeping the errors of rapid evaluations under control (Y. Jin et al., 2019) . Traditional SAEA uses conventional machine learning methods as surrogate models. The results of refined evaluations are used as new training samples, and the surrogate model can be updated by retraining the machine learning model. Since conventional machine learning methods have limited trainable parameters, their training generally takes only a few minutes or even seconds, making the cost of retraining acceptable. However, the generalizable surrogate model used in this study is based on a deep GNN (see Section 4), which has a large number of trainable parameters and requires hundreds of minutes to train. The cost of retraining the GNN is too high, thus necessitating a new strategy for model updating.

A distance-based surrogate model evaluation and updating strategy is proposed herein. The distances are measured between the design variable vectors of different candidate solutions. When the distances between different candidate solutions are small, an identical error correction factor can be used to adjust the predictions of the surrogate model. This avoids calculating the error correction factor for each candidate solution repeatedly, thereby saving computational time. The error correction factor is obtained by comparing the refined calculation results of FE models with the rapid prediction results of GNN.

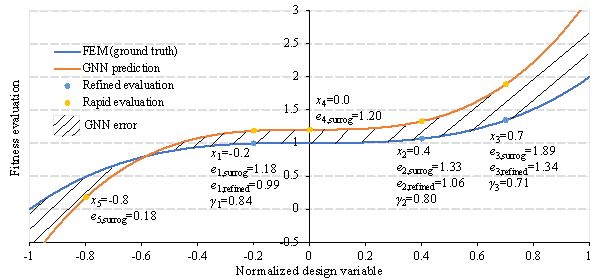

The proposed method is feasible and applicable for optimization problems without high nonlinearity, e.g., shear-wall structural design in the schematic design phase, which requires only linear or equivalent linear analysis. In these circumstances, the following phenomena can be observed: The GNN model used in this study exhibits continuity, which forms the basis for using gradient-based algorithms (e.g., gradient descent) for training. Therefore, minor changes in the input to the model only result in slight variations in the model's predictions, as shown by the orange curve in Figure 9. Meanwhile, the ground truth that the model aims to predict is also continuous. Minor changes in the design information (e.g., the length of a shear wall) only cause small variations in the physical responses and material usage, as depicted by the blue curve in Figure 9. Hence, for minor changes in the model input, the error of the model prediction from the ground truth also varies marginally, as indicated by the shaded area in Figure 9. When the distances between several design variable vectors are small (e.g., x1, x2, and x4 in Figure 9), the errors in their model predictions are relatively similar, and an identical error correction factor can be roughly used to adjust the evaluation results of the surrogate model. Definitions of distance and the error correction factor can be found in Section 5.2.

Figure 9 Schematic diagram of distance-based model evaluation and updating

Similar to the existing distance-based model updating methods (Branke & Schmidt, 2005) , the proposed method can enhance the exploration of unknown design spaces that have not been visited by the EA (Črepinšek et al., 2013) . However, existing distance-based model updating methods require adding refinedly evaluated design variable vectors to the training samples, followed by retraining of the surrogate model. In contrast, the proposed method does not require the surrogate model to be retrained but directly adjusts the prediction results, featuring a significant difference and advantage to the existing approaches.

5.2 Algorithm implementation

For a given design variable vector to be evaluated, calculate its distance d from the design variable vectors that have already been refinedly evaluated, to determine whether an identical error correction factor can be used. The definition of the distance d is given in Equation (7):

|

|

(7) |

where ![]() and

and ![]() represent the design variable vector to be evaluated and

the one that has been refinedly evaluated, respectively;

represent the design variable vector to be evaluated and

the one that has been refinedly evaluated, respectively; ![]() and

and ![]() represent the i-th design variable of the vector

to be evaluated and the one that has been refinedly evaluated, respectively;

and n is the dimension or the number of design variables. The design

variables should be normalized, i.e.,

represent the i-th design variable of the vector

to be evaluated and the one that has been refinedly evaluated, respectively;

and n is the dimension or the number of design variables. The design

variables should be normalized, i.e., ![]() , to ensure that the influence of each design variable on

d is the same.

, to ensure that the influence of each design variable on

d is the same.

It can be observed that d

is the Manhattan distance (Suwanda et al., 2020) between ![]() and

and ![]() divided by twice their dimension. The use of the Manhattan

distance is due to its robustness being superior to the commonly used Euclidean

distance, making it less susceptible to the influence of significant changes

in individual design variables. After dividing by twice the dimension, the

range of d becomes independent of

the number of design variables, that is,

divided by twice their dimension. The use of the Manhattan

distance is due to its robustness being superior to the commonly used Euclidean

distance, making it less susceptible to the influence of significant changes

in individual design variables. After dividing by twice the dimension, the

range of d becomes independent of

the number of design variables, that is, ![]() . According to the requirements for optimization efficiency, a distance

threshold

. According to the requirements for optimization efficiency, a distance

threshold ![]() is defined.

is defined.

(1) When the distance between two design variable vectors is small,

that is, ![]() , the error correction factor of the refinedly evaluated vector

can be used to adjust the vector to be evaluated, as shown in Equation (8):

, the error correction factor of the refinedly evaluated vector

can be used to adjust the vector to be evaluated, as shown in Equation (8):

|

|

(8) |

where ![]() is the adjusted evaluation result of the surrogate model

for

is the adjusted evaluation result of the surrogate model

for ![]() ,

, ![]() is the original prediction result by the surrogate model

for

is the original prediction result by the surrogate model

for ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the error correction factor of the refinedly evaluated

vector, as shown in Equation (9):

is the error correction factor of the refinedly evaluated

vector, as shown in Equation (9):

|

|

(9) |

where ![]() is the evaluation result of the refined method for

is the evaluation result of the refined method for ![]() ,

, ![]() is the evaluation result of the surrogate model for

is the evaluation result of the surrogate model for ![]() .

.

Note that when multiple design variable vectors satisfy the

distance threshold ![]() , Equations (8)-(9) should be calculated based on the refinedly

evaluated design variable vector with the smallest distance.

, Equations (8)-(9) should be calculated based on the refinedly

evaluated design variable vector with the smallest distance.

(2) When the distance between two design

variable vectors is greater than the predefined threshold ![]() , that is,

, that is, ![]() , or there is no refinedly evaluated vector

, or there is no refinedly evaluated vector ![]() , the vector

, the vector ![]() should be refinedly evaluated based on FE model. Then, the refinedly

evaluated design variable vector and its error correction factor should be

recorded.

should be refinedly evaluated based on FE model. Then, the refinedly

evaluated design variable vector and its error correction factor should be

recorded.

To facilitate understanding, Figure

9 provides a schematic diagram of a simple scenario, where there is only one

design variable, i.e., n=1. Here, x1, x2,

and x3 are design variables that have been refinedly evaluated,

while x4 and x5 are design variables awaiting

evaluation. Define ![]() and conduct a fitness evaluation for x4

and x5 outlined below.

and conduct a fitness evaluation for x4

and x5 outlined below.

(1) According to Equation (7), the distances

from x4 to x1, x2, and

x3 are 0.1, 0.2, and 0.35, respectively. Therefore, the distances

from x4 to both x1 and x2

are less than ![]() . x1 is the closest to x4,

and the corresponding error correction factor 污1=0.84, according to Equation (9). The adjusted

evaluation result of x4 is calculated as

. x1 is the closest to x4,

and the corresponding error correction factor 污1=0.84, according to Equation (9). The adjusted

evaluation result of x4 is calculated as ![]() , according to Equation (8).

, according to Equation (8).

(2) According to Equation (7), the distances

from x5 to x1, x2, and

x3 are 0.3, 0.6, and 0.75, respectively. Therefore, the

distances from x5 to x1, x2,

and x3 are all greater than ![]() . In this situation, x5 needs to be refinedly

evaluated.

. In this situation, x5 needs to be refinedly

evaluated.

Algorithm 1 Surrogate model evaluation and updating strategy

|

Input: |

Maximum allowable

distance for surrogating fitness evaluation |

|

Output: |

Optimal solution

|

|

for

|

|

|

if add

add

else //Applicable correction factors are found if

end for |

|

Note:

![]() is an empty set.

is an empty set.

The details of the proposed surrogate model evaluation and updating strategy are elaborated in Algorithm 1. It is worth noting that the refinedly evaluated solutions are also used to update the surrogate model, as in traditional SAEAs. However, these solutions are not used to retrain the surrogate model. Instead, they are used to calculate an error correction factor. The surrogate model is updated by multiplying the prediction result by the error correction factor. The choice of the error correction factor depends on the distance between two solutions, as the term ※distance-based§ suggests.

5.3 Parameter assessment

Numerical experiments are conducted on the same personal

computer as described in Section 4.4. The performance of the proposed GAEA

is significantly influenced by the distance threshold ![]() , which determines the frequency of using FE models for refined evaluations.

When

, which determines the frequency of using FE models for refined evaluations.

When ![]() , GAEA solely relies on FE models for refined evaluations and degrades

into a traditional EA. When

, GAEA solely relies on FE models for refined evaluations and degrades

into a traditional EA. When ![]() , GAEA exclusively uses the GNN surrogate model for rapid evaluations

without updating the surrogate model. When

, GAEA exclusively uses the GNN surrogate model for rapid evaluations

without updating the surrogate model. When ![]() , GAEA's fitness evaluations utilize both the FE model and the GNN

surrogate model. This section will discuss the optimization outcomes and the

time consumptions of GAEA for

, GAEA's fitness evaluations utilize both the FE model and the GNN

surrogate model. This section will discuss the optimization outcomes and the

time consumptions of GAEA for ![]() .

.

Meanwhile, the proposed strategy can be applied to both EA and SAEA to enhance their efficiency. The genetic algorithm (GA, a classic EA) and the online learning algorithm (OL, a widely used state-of-the-art SAEA) provided by YJK-GAMA (GAMA, 2023a) are used in this study as supporting algorithms. Online learning is an ensemble learning-based SAEA, utilizing several heterogeneous surrogate models for promoting ensemble diversity (Guo et al., 2019; Garza-Fabre et al., 2024) , such as polynomial regression, truncated Fourier series, support vector machine, and radial basis function networks.

For parameter selection, the number of fitness evaluations is chosen based on a parameter assessment. When the evaluation number is 50, the average reduction in the total objective function is 15.9%. When this number is 100, the average reduction is 22.1%, which is 6.2% lower than that from 50 evaluations. When this number is 200, the further reduction compared to 100 evaluations is smaller than 3%. Therefore, the number of fitness evaluations is set as 100, providing a balance between optimization time and effectiveness. The other parameters of GA and OL are set according to the recommendations in the YJK-GAMA official documentation, as given in Table 5. When employing different supporting algorithms and distance thresholds, different GAEAs are designated as shown in Table 6. To reduce the impact of case specificity on the experimental results, all experiments are repeated on the five typical cases presented in Section 2.3, and the results are averaged.

Table 5 Parameter setting of supporting evolutionary algorithms

|

Algorithm |

Parameter |

Value |

|

Genetic algorithm |

Number of iterations |

10 |

|

Fitness evaluations in each iteration |

10 |

|

|

Distribution index of crossover operator |

20 |

|

|

Crossover probability |

0.9 |

|

|

Distribution index of mutation operator |

20 |

|

|

Mutation probability |

1 |

|

|

Online learning |

Maximum number of fitness evaluations |

100 |

|

Initial sample number |

10 |

Table 6 Details of different evolutionary algorithms

|

Designation |

Supporting algorithm |

Distance threshold

|

|

GAEA-GA-1 |

Genetic algorithm |

1 |

|

GAEA-OL-1 |

Online learning |

1 |

|

GAEA-GA-0.25 |

Genetic algorithm |

0.25 |

|

GAEA-OL-0.25 |

Online learning |

0.25 |

|

GAEA-GA-0.125 |

Genetic algorithm |

0.125 |

|

GAEA-OL-0.125 |

Online learning |

0.125 |

|

GA |

Genetic algorithm |

0 |

|

OL |

Online learning |

0 |

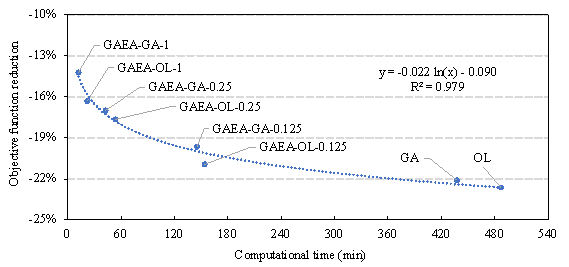

5.3.1 Comparison under identical numbers of fitness evaluations

When given an identical number of fitness evaluations (100

evaluations), the optimization outcomes are compared between the proposed

GAEA and the traditional methods. After optimizations with various supporting

algorithms and ![]() , the average reduction in the total objective function and the computational

time are summarized in Table 7. Overall, the longer the computational time,

the greater the reduction in the total objective function. The computational

time in relation to the average reduction in the total objective function

demonstrates a logarithmic relationship (R2=0.979). The effect

of lengthening the computational time marginally decreases with the objective

function getting smaller, as shown in Figure 10.

, the average reduction in the total objective function and the computational

time are summarized in Table 7. Overall, the longer the computational time,

the greater the reduction in the total objective function. The computational

time in relation to the average reduction in the total objective function

demonstrates a logarithmic relationship (R2=0.979). The effect

of lengthening the computational time marginally decreases with the objective

function getting smaller, as shown in Figure 10.

Table 7 Relative changes of the total objective function after optimizations

|

Designation |

Objective function reduction |

Computational time (min) |

Percentage of refined evaluations |

|

GAEA-GA-1 |

-14.2% |

12.2 |

0.0% |

|

GAEA-OL-1 |

-16.3% |

21.9 |

0.0% |

|

GAEA-GA-0.25 |

-17.0% |

42.7 |

7.3% |

|

GAEA-OL-0.25 |

-17.6% |

53.5 |

7.7% |

|

GAEA-GA-0.125 |

-19.6% |

145.4 |

29.3% |

|

GAEA-OL-0.125 |

-20.9% |

153.9 |

28.0% |

|

GA |

-22.1% |

437.6 |

100.0% |

|

OL |

-22.6% |

486.9 |

100.0% |

Experimental results demonstrate that for a fixed supporting

algorithm, as ![]() decreases, the objective function gradually declines while

the time consumption gradually increases. This is due to the increased evaluation

accuracy and time consumption of fitness evaluations as the frequency of FE

model evaluations rises. As shown in Table 7, when

decreases, the objective function gradually declines while

the time consumption gradually increases. This is due to the increased evaluation

accuracy and time consumption of fitness evaluations as the frequency of FE

model evaluations rises. As shown in Table 7, when ![]() , the percentage of refined evaluations is approximately 8%; when

, the percentage of refined evaluations is approximately 8%; when

![]() , this percentage increases to approximately 30%. Simultaneously, for

a fixed

, this percentage increases to approximately 30%. Simultaneously, for

a fixed ![]() , using OL as a supporting algorithm consumes more time but also yields

better results. This is because OL requires training and updating of traditional

machine-learning surrogate models, which consumes extra time compared to GA.

However, by exploring the design space using the surrogate model, better design

solutions can be discovered.

, using OL as a supporting algorithm consumes more time but also yields

better results. This is because OL requires training and updating of traditional

machine-learning surrogate models, which consumes extra time compared to GA.

However, by exploring the design space using the surrogate model, better design

solutions can be discovered.

Figure 10 Relationship between average objective function reduction and computational time

On average, when ![]() , GAEA can achieve 64.4% of GA*s optimization outcome using only 2.8%

of its computational time, or 72.1% of OL's optimization outcome using 4.5%

of its computational time. When

, GAEA can achieve 64.4% of GA*s optimization outcome using only 2.8%

of its computational time, or 72.1% of OL's optimization outcome using 4.5%

of its computational time. When ![]() , GAEA can achieve 76.9% of GA's optimization outcome with 9.8% of

its computational time, or 78.0% of OL's optimization outcome with 11.0% of

its computational time. When

, GAEA can achieve 76.9% of GA's optimization outcome with 9.8% of

its computational time, or 78.0% of OL's optimization outcome with 11.0% of

its computational time. When ![]() , GAEA can achieve 88.9% of GA's optimization outcome with 33.2% of

its computational time, or 92.5% of OL's optimization outcome with 31.6% of

its computational time.

, GAEA can achieve 88.9% of GA's optimization outcome with 33.2% of

its computational time, or 92.5% of OL's optimization outcome with 31.6% of

its computational time.

It is important to note that depending on the value of

![]() , GAEA can save 66.8% to 97.2% computational time compared to methods

without employing GNNs. In contrast, other recently proposed SAEA methods

only offer a reduction of computational time by 30% (Lou et al., 2021) and 26% (Huang et al., 2023) . Although the time reductions in this study are calculated

based on different cases, they represent a fair comparison between the proposed

GAEA and the existing SAEAs, without being influenced by the complexity of

various cases. Therefore, the proposed GAEA has a significant efficiency

advantage over the existing SAEAs.

, GAEA can save 66.8% to 97.2% computational time compared to methods

without employing GNNs. In contrast, other recently proposed SAEA methods

only offer a reduction of computational time by 30% (Lou et al., 2021) and 26% (Huang et al., 2023) . Although the time reductions in this study are calculated

based on different cases, they represent a fair comparison between the proposed

GAEA and the existing SAEAs, without being influenced by the complexity of

various cases. Therefore, the proposed GAEA has a significant efficiency

advantage over the existing SAEAs.

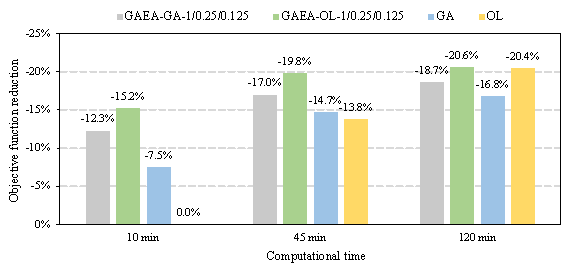

5.3.2 Comparison under identical computational time

For a given identical computational time, the optimization

outcomes are compared between the proposed GAEA and the conventional methods.

As discussed in Section 2.1, the optimization time periods are set at 10,

45, and 120 min, respectively. These durations can well accommodate the working

pace of engineers in the scheme design phase. According to the experimental

results shown in Table 7, for a 10-min optimization task, ![]() can be used; for a 45-min optimization task,

can be used; for a 45-min optimization task, ![]() is suitable; and for a 120-min optimization task,

is suitable; and for a 120-min optimization task, ![]() is recommended.

is recommended.

Figure 11 Objective function reduction for given identical computational time

Figure 11 shows the average reduction in the total objective function after being optimized by various algorithm configurations when the same computational time is consumed. It can be observed that the optimization outcome using OL as the supporting algorithm is superior to that when using GA. This is because OL itself constructs machine-learning surrogate models, which can search the design space more effectively. Therefore, it is recommended to use OL as the supporting algorithm of GAEA, and the following sections will compare the results of GAEA-OL with GA and OL. Specifically:

(1) When the available optimization time is 10 min, GAEA-OL-1 (-15.2%) > GAEA-GA-1 (-12.3%) > GA (-7.5%) >> OL (0.0%). This is because, within 10 min, GAEA can complete around 100 fitness evaluations through GNN. In contrast, GA can only perform several evaluations using FE models. OL, which needs to build a dataset, is yet to complete the training of the surrogate models within the 10-min time slot, and its optimization will not start. The total objective function reduction achieved by GAEA-OL-1 is significantly higher than the traditional methods, being 2.03 times that of GA.

(2) When the available time is 45 min, GAEA-OL-0.25 (-19.8%) > GAEA-GA-0.25 (-17.0%) > GA (-14.7%) > OL (-13.8%). At this point, OL has completed the training of the surrogate models, which significantly improves the efficiency of fitness evaluation, and its optimization outcome gradually approaches that of GA. Nevertheless, GAEA still maintains a leading advantage over GA and OL. The total objective function reduction achieved by GAEA-OL-0.25 is significantly higher than the traditional methods, being 1.43 times that of OL and 1.35 times that of GA.

(3) When the available time is 120 min, GAEA-OL-0.125 (-20.6%) > OL (-20.4%) > GAEA-GA-0.125 (-18.7%) > GA (-16.8%). This is because, as training samples related to this specific structure case are accumulated, the traditional case-specific surrogate model gradually approaches the generalizable GNN surrogate model in terms of evaluation accuracy. The total objective function reduction achieved by GAEA-OL-0.125 is slightly higher than the traditional SAEA, being 1.01 times that of OL. It is still significantly higher than the traditional EA, being 1.23 times that of GA.

Additionally, paired sample t-tests are conducted to evaluate the statistical significance of the mean reduction in the objective function by GAEA optimization compared to those by GA or OL. The null hypothesis states that the mean reduction in the objective function by GAEA optimization is less than that by GA or OL. The p-values for comparing GAEA-OL with GA and OL are presented in Table 8, and the significance level 汐 is set as 0.1. A p-value lower than 汐 leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis, suggesting that the mean reduction in the objective function by GAEA optimization is statistically not less than that by GA or OL. When comparing GAEA-OL-0.125 with OL, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, indicating that GAEA-OL-0.125 is not significantly superior to OL. In other circumstances, the null hypothesis is rejected, affirming that the effectiveness of GAEA is statistically significant.

Table 8 P-values of the t-tests

|

GAEA-OL-1 |

GAEA-OL-0.25 |

GAEA-OL-0.125 |

|

|

GA |

0.081 |

0.031 |

0.064 |

|

OL |

0.016 |

0.042 |

0.436 |

6 Case study

6.1 Detailed discussion on a typical case

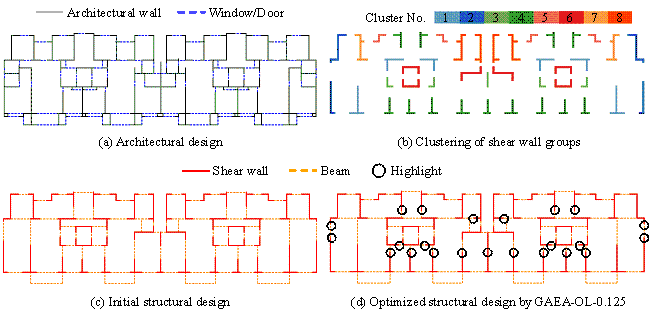

To intuitively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method for rapid optimization, a detailed case study is conducted on Case 5 of Section 2.3. The architectural design of Case 5 is illustrated in Figure 12(a), the clustering of the shear walls is shown in Figure 12(b), and the initial structural design is given in Figure 12(c). The design conditions are presented in Table 1. For the three optimization timing scenarios discussed in Section 2.1, the proposed GAEA (GAEA-OL-1/0.25/0.125, according to the recommendation given in Section 5.3.2), a traditional EA (GA), and a state-of-the-art ensemble learning-based SAEA (OL) are also used to perform the optimization design for Case 5. The parameter settings can be seen in Section 5.3.

Figure 12 Design information and design result of Case 5

The physical responses and the material costs before and

after optimization are shown in Table 9. As per the Chinese design code

(MOHURD, 2010) , the shear-wall structure of Case 5 should

meet the following criteria: ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Meanwhile, the material cost

. Meanwhile, the material cost ![]() and the proportion of shear walls with an excessive axial

compression ratio

and the proportion of shear walls with an excessive axial

compression ratio ![]() should be as small as possible. The initial structural

design before optimization has an issue of having

should be as small as possible. The initial structural

design before optimization has an issue of having ![]() exceeding the code limit. The results of the case study

indicate that:

exceeding the code limit. The results of the case study

indicate that:

Table 9 Design performances of Case 5 before and after optimization

|

Optimization time |

Designation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 min |

Initial |

1.96℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.107% |

0.857 |

0.168 |

0 |

|

10 min |

GAEA-OL-1 |

1.70℅106 |

1.55℅106 |

0.094% |

0.830 |

0.176 |

0 |

|

GA |

1.92℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.106% |

0.847 |

0.170 |

0 |

|

|

OL |

1.96℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.107% |

0.857 |

0.168 |

0 |

|

|

45 min |

GAEA-OL-0.25 |

1.60℅106 |

1.54℅106 |

0.091% |

0.771 |

0.175 |

0 |

|

GA |

1.81℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.103% |

0.825 |

0.175 |

0 |

|

|

OL |

1.77℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.102% |

0.789 |

0.176 |

0 |

|

|

120 min |

GAEA-OL-0.125 |

1.57℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.090% |

0.796 |

0.176 |

0 |

|

GA |

1.81℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.103% |

0.825 |

0.175 |

0 |

|

|

OL |

1.63℅106 |

1.53℅106 |

0.094% |

0.776 |

0.175 |

0 |

(1) After 10 min of optimization, the values of

![]() resulting from the GA and OL*s designs still exceed the

code limit, leading to a failed optimization, and

resulting from the GA and OL*s designs still exceed the

code limit, leading to a failed optimization, and ![]() has not reduced significantly. All the physical responses

of GAEA-OL-1*s design result comply with the design code, signifying successful

optimization. However, its

has not reduced significantly. All the physical responses

of GAEA-OL-1*s design result comply with the design code, signifying successful

optimization. However, its ![]() increases by 1.3% compared to that of the initial design.

increases by 1.3% compared to that of the initial design.

(2) After 45 min of optimization, ![]() of the GA and OL*s design results again exceed the code

limit, resulting in a failed optimization, although

of the GA and OL*s design results again exceed the code

limit, resulting in a failed optimization, although ![]() has reduced significantly. All the physical responses of

GAEA-OL-0.25*s design result comply with the design code, implying successful

optimization. However, its

has reduced significantly. All the physical responses of

GAEA-OL-0.25*s design result comply with the design code, implying successful

optimization. However, its ![]() increases by 0.7% compared to that of the initial design.

increases by 0.7% compared to that of the initial design.

(3) After 120 min of optimization, GA fails to find a better

design scheme than the 45-min scenario, which is still a failed optimization.

All the physical responses of GAEA-OL-0.125 and OL*s design results comply

with the design code, confirming a successful optimization, and their

![]() values are not increased compared to the initial design.

The total objective function of GAEA-OL-0.125 is 3.7% lower than that of OL,

resulting from its design result having a more rational safety redundancy.

The structural design of GAEA-OL-0.125 after optimization is shown in Figure

12(d), and the differences between the optimized design from the initial one

are highlighted with circles. It can be seen that the optimized structural

design does not affect the functional space of the building and satisfies

empirical design rules such as maintaining symmetry.

values are not increased compared to the initial design.

The total objective function of GAEA-OL-0.125 is 3.7% lower than that of OL,

resulting from its design result having a more rational safety redundancy.

The structural design of GAEA-OL-0.125 after optimization is shown in Figure

12(d), and the differences between the optimized design from the initial one

are highlighted with circles. It can be seen that the optimized structural

design does not affect the functional space of the building and satisfies

empirical design rules such as maintaining symmetry.

In summary, the proposed GAEA can meet the code compliance requirements of shear-wall structures for three optimization timing scenarios: 10, 45, and 120 min. Additionally, the longer the optimization duration, the better the design performance in terms of material cost and safety redundancy. Traditional GA fails to meet the rapid optimization needs for the aforementioned three scenarios, and existing OL fails for 10 and 45 min scenarios.

In engineering practice, the proposed GAEA can be easily integrated with the structural design software YJK-GAMA. Through secondary development, the FE model of the shear-wall structure will be updated in real-time in YJK-GAMA during the entire optimization process. After the optimization is completed, the FE model of the optimal design scheme can be seamlessly used in the subsequent phases for detailed design and construction drawing design. Therefore, a simple user training program will be sufficient for engineers to benefit from using the proposed GAEA.

6.2 Discussion on the scalability

To demonstrate the scalability of the proposed method

on larger and more complex structures, two more case studies are conducted

on Cases 1 and 2, which are high-rise buildings with 24 and 26 stories, respectively.

For each case, 45 minutes are allocated for optimization design. The initial

and the optimized structural designs are given in Figure 13, and the design

metrics before and after optimization are given in Table 10 with highlighted

values being discussed. As per the Chinese design code (MOHURD,

2010) , the shear-wall structure of Cases 1 and 2

should meet the same criteria as Case 5, except that

![]() (Case 1) and

(Case 1) and ![]() (Case 2).

(Case 2).

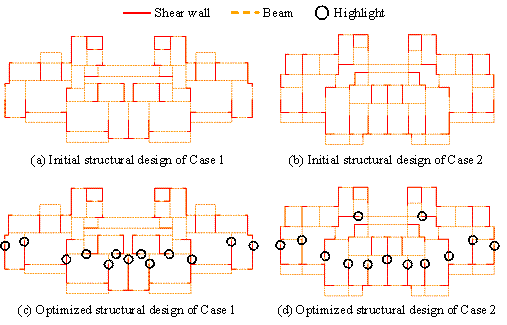

Figure 13 Design results of Cases 1 and 2

For Case 1, the initial structural design before optimization has issues

of having ![]() exceeding the code limit and having

exceeding the code limit and having

![]() that is too large. After 45 minutes of optimization,

GAEA-OL-0.25*s design result has a

that is too large. After 45 minutes of optimization,

GAEA-OL-0.25*s design result has a ![]() that complies with the code limit and a

that complies with the code limit and a

![]() that is 72.1% smaller. In contrast, GA and OL*s design

results have a

that is 72.1% smaller. In contrast, GA and OL*s design

results have a ![]() that remains unchanged and a

that remains unchanged and a

![]() that is only 47.1% and 36.7% smaller, respectively.

that is only 47.1% and 36.7% smaller, respectively.

For Case 2, the initial structural design prior to optimization has

issues of having ![]() and

and ![]() exceeding the code limit. After 45 minutes of optimization,

GAEA-OL-0.25*s design result has both