1. Introduction

Designing building structures is a time-consuming and labor-intensive task. Its primary objective is to minimize material consumption (ensuring economic and environmental efficiency), while satisfying certain design requirements (safety and usability). To enhance automation in structural design, extensive research has been conducted on structural optimization algorithms, particularly heuristic algorithms, such as genetic algorithms (GAs), simulated annealing (SA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO) [1,2] . This approach, which applies optimization methods to design, is referred to as optimization design. However, the efficiency and effectiveness of traditional structural optimization algorithms remain unsatisfactory, making it challenging to obtain satisfactory design solutions within an acceptable time frame. Consequently, their application is limited in practical engineering projects. Recent advancements in computing power, algorithms, and data have driven a global wave of artificial intelligence (AI), including machine learning and deep learning, which have achieved remarkable success in fields, such as computer vision and natural language processing. When trained on large datasets, AI can learn and handle complex tasks effectively, thus giving rise to the phrase ※data-driven approach§. AI introduces new possibilities in traditional structural optimization and helps develop data-driven intelligent optimization methods that offer significant potential for solving structural design problems more efficiently and effectively.

The fundamental distinction between intelligent and traditional optimization methods lies in their ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills. Data-driven AI possesses this ability by saving trained model parameters and utilizing them for prediction. Consequently, by integrating data-driven AI with structural optimization, intelligent optimization methods can learn and internalize design experience and principles, or, in other words, exhibit memory [3] . With the rapid advancement of AI technologies, various novel intelligent algorithms are continuously emerging, demonstrating enhanced learning capabilities and finding increasingly diverse applications in optimization design.

Numerous researchers have conducted reviews on the optimization design of building structures, including high-rise [2] and reinforced concrete (RC) [1] building structures. However, these studies have not emphasized the role of data-driven AI in the optimization process. Several reviews have also focused on surrogate-assisted optimization algorithms [4每6] . Nevertheless, these studies have primarily highlighted the application of traditional machine learning algorithms in enhancing performance evaluation, while overlooking modern AI algorithms and their contributions to other stages of optimization. Other studies have reviewed the integration of machine learning or deep learning with optimization algorithms [7每9] ; yet these studies have failed to address the specific requirements of structural design in construction. Recently, some researchers have reviewed the role of AI in optimizing steel frame structures; however, they have not extended their focus to other structural types [10] . Additionally, reviews on automation of architectural and structural design have largely focused on deep generative models and topology optimization [11] . Thus, comprehensive reviews addressing intelligent optimization design, specifically for building structures, have been scarce.

2. Literature review method and statistics

The scope of this review encompasses the intersection of three research domains: building structures, data-driven methods, and optimization design. Consequently, a literature search was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection, with the search scope set to topic (including title, abstract, author keywords, and keywords plus). The search criteria were designed to address all three research domains simultaneously and required the Web of Science categories to be limited to Engineering Civil, as summarized in Table 1. For building structures, the search terms included common structural types, such as ※building,§ ※frame,§ ※shear wall,§ and ※truss,§ as well as ※structur*§ (with * as a wildcard) to focus specifically on structural rather than architectural design. For data-driven methods, the search terms encompassed commonly used expressions, such as ※surrogate,§ ※metamodel,§ and ※AI,§ as well as specific data-driven methods, including ※response surface,§ ※Kriging,§ ※neural network,§ and ※diffusion model.§ For optimization design, the search term ※optimiz*§ and ※design§ was used. Using this approach, a total of 394 articles were retrieved, which were then individually reviewed, screened, and supplemented with relevant literature previously identified by the authors; ultimately, this resulted in 167 articles that strictly aligned with the scope of this study.

Table 1 Search object and formula used in Web of Science Core Collection and resulting number of studies (accessed on Jan. 1, 2025).

|

Search object |

Search formula |

Web of Science category |

Number of studies |

|

Data-driven intelligent optimization design for building structures |

TS = (※building§ OR ※frame§ OR ※shear wall§ OR ※truss§ OR ※grid§ OR ※shell§) AND TS = (※structur*§) AND TS = (※optimiz*§) AND TS = (※design§) AND TS = (※surrogate§ OR ※metamodel§ OR ※artificial intelligenc*§ OR ※AI§ OR ※machine learning§ OR ※polynomial regression§ OR ※response surface§ OR ※Kriging§ OR ※Gaussian process§ OR ※radial basis function§ OR ※support vector§ OR ※decision tree§ OR ※random forest§ OR ※neural network§ OR ※deep learning§ OR ※long short-term memory§ OR ※variational autoencoder§ OR ※generative adversarial network§ OR ※transformer§ OR ※diffusion model§ OR ※large language model§ OR ※reinforcement learning§ OR ※clustering§) |

Engineering Civil |

394 |

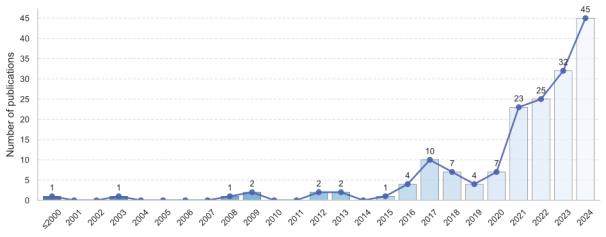

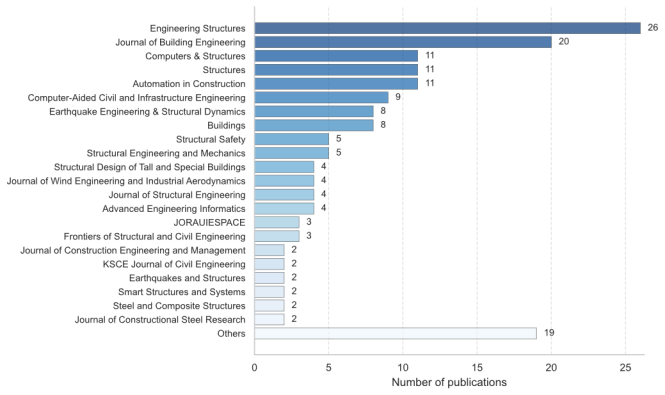

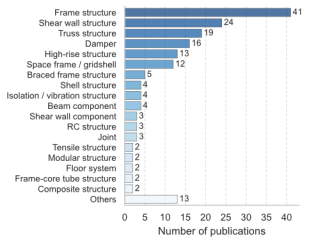

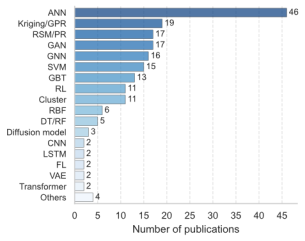

The 167 selected articles were statistically analyzed in terms of publication year, source, optimization design objectives, data-driven AI algorithms, optimization algorithms, and the role of AI in optimization design, as illustrated in Figure 1.

2.1 Publication trends & sources

The earliest relevant study dates back to 1997, when an artificial neural network (ANN)-accelerated GA was applied to optimizing steel structures [12] . However, until 2016, the number of related studies remained minimal. In contrast, since 2017, driven by the resurgence of AI technologies and their application in structural engineering, the research volume has increased significantly, exceeding 20 articles annually until 2021, and then surpassing 40 articles annually until 2024. In terms of the publication sources, the relevant studies were primarily published in leading journals within the structural engineering field or at the intersection of computing and civil engineering. Engineering Structures leads with 26 articles (16%), followed by Journal of Building Engineering, Computers & Structures, Structures, Automation in Construction, and Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering.

2.2 Design objects

In terms of design objects in intelligent optimization, RC frame structures are the most commonly studied category [13] , with 40 publications (24%). Among these, steel frame structures [14] constituted 22 studies (13%). Shear wall structures [15] followed closely, with 24 publications (14%). RC frames and shear wall structures have emerged as the most prevalent design targets because of their extensive application in residential buildings and relatively straightforward computational and design processes, which make them suitable for exploring new technologies and methods. More complex systems such as truss structures [16] , dampers (viscous [17] , slit [18] , and tuned-mass [19] ), high-rise structures [20] , and long-span structures (space frame [21] , gridshell [22] , and tensile [23] ) have also received significant research attention. In addition to these commonly studied structural systems, intelligent optimization has been recently applied to unique structures, including aerial building machines [24] , modular buildings [25] , and mega-frame structures [26] , indicating a continuous expansion of its application scope.

2.3 AI algorithms

Among AI-driven intelligent optimization algorithms, ANNs are the most commonly employed, accounting for 27% of the applications [27] . As the simplest type of neural networks, ANN often outperforms most traditional machine learning algorithms, while demonstrating strong generalization capabilities; furthermore, its function approximation properties make it the most widely utilized method. Following ANN, Kriging models or Gaussian process regression (GPR) [28,29] , response surface methodology (RSM) or polynomial regression (PR) [30,31] , and support vector machines (SVMs) [32] are also frequently adopted, with application proportions of 11%, 10%, and 9%, respectively. These three approaches are well-established traditional machine learning techniques for constructing surrogate models. More recent techniques include generative adversarial networks (GANs) [33] (10%), graph neural networks (GNNs) [34] (10%), and gradient boosted trees (GBTs) [35] (8%), representing methodologies based on image representation, graph representation, and ensemble learning, respectively. Unsupervised learning [36] and reinforcement learning (RL) [37] are emerging but still relatively underrepresented (7% each).

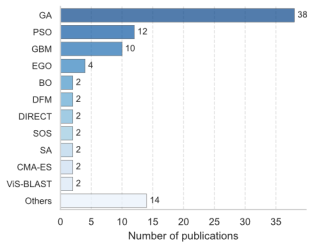

2.4 Optimization algorithms

In the field of intelligent optimization algorithms, a total of 89 studies explicitly specify the optimization methods employed. Among them, GAs [38] are the most widely applied (43%), significantly surpassing other optimization techniques. PSO [39] follows, with a share of 13%. Gradient-based methods (GBMs), such as the conjugate gradient methods (CGMs) [40] and sequential quadratic programming (SQP) [41] , are also utilized. Additionally, surrogate model-driven global optimization approaches, including efficient global optimization (EGO) [28] , Bayesian optimization (BO) [42] , desirability function methods (DFMs) [43] , and deterministic global optimization algorithms, such as Dividing Rectangles (DIRECT) [30] , have been applied. Overall, heuristic algorithms are used far more frequently than GBMs. In addition to GA and PSO, approximately 20 different heuristic algorithms have been identified in the literature, including symbiotic organisms search (SOS) [44] , SA [45] , covariance matrix adaptation evolution strategy (CMA-ES) [18] , and violation-based sensitivity analysis and borderline adaptive sliding technique (ViS-BLAST) [46] . Although each of these additional heuristic algorithms appears only once or twice, their cumulative occurrence remains substantial.

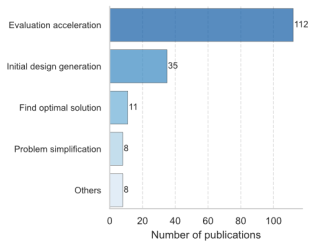

2.5 AI*s role in optimization

Further analysis was conducted on the role of data-driven AI in optimization algorithms. The most common contribution of AI in optimization is accelerating the evaluation of design solutions [35] (67%). For computationally expensive optimization problems, where high-fidelity numerical simulations are required to assess the design performance, the integration of AI-based surrogate models can significantly reduce the computational costs and enhance optimization efficiency [4,5] . Another key role of AI in optimization is to generate initial design solutions [47] (21%). Initiating the optimization process with a well-informed initial design typically leads to faster convergence toward superior solutions [48] . Moreover, AI can learn the process of searching for optimal solutions [14] (7%), thereby enabling a more efficient discovery of optimal designs. Trained RL models can be used to develop general strategies for identifying optimal solutions and achieving comparable or even superior results with significantly fewer evaluations than conventional optimization algorithms. Additionally, AI can extract patterns and features from data to facilitate clustering and dimensionality reduction, thereby reducing problem complexity in various aspects, including optimization variable definition [49] , surrogate model construction [50] , and design result aggregation [40] . This application accounts for 5% of the studies reviewed.

|

(a) |

|

|

(b) |

|

|

(c) |

(d) |

|

(e) |

(f) |

Figure 1. Statistical data related to the reviewed literature (some studies employ multiple methods, leading to repeated counts). (a) Publication year. (b) Publication title (The abbreviation ※JORAUIESPACE§ refers to ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part A: Civil Engineering). (c) Design object. (d) AI algorithm. (e) Optimization algorithm. (f) AI*s role in optimization.

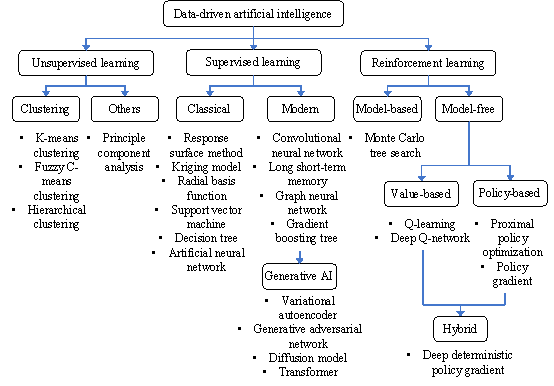

3. Taxonomy of data-driven AI and optimization algorithms

3.1 Data-driven AI algorithms

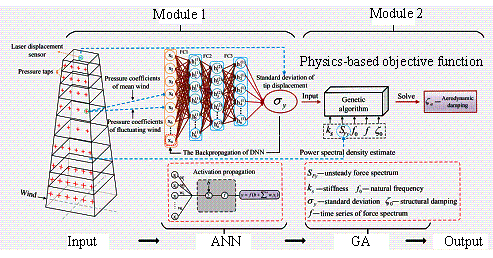

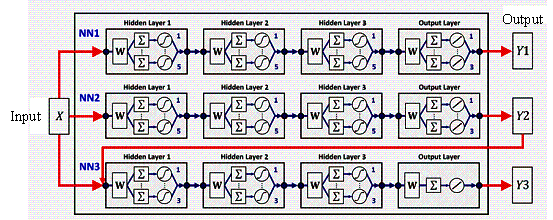

Data-driven AI algorithms are utilized to enable intelligent optimization to learn and master design experience and patterns. Based on the training approaches used, data-driven AI algorithms in structural design can be categorized into three main types: unsupervised learning, supervised learning, and RL, as illustrated in Figure 2.

(1) Unsupervised learning processes unlabeled data to uncover the underlying structures and patterns. In the context of intelligent optimization, unsupervised learning primarily includes clustering algorithms, e.g., K-means [51] , fuzzy C-means [52] , and clustering [53] . Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) methods [50] are also widely employed.

(2) Supervised learning learns from labeled training data to establish a mapping function that enables accurate prediction of outputs (labels), given new inputs. Supervised learning can be further divided into classical and modern approaches. Classical approaches rely heavily on manual feature engineering and offer relatively simple, interpretable models that are efficient on smaller datasets. Common examples include RSM or PR [30,31] , Kriging models or GPR [28,29] , radial basis function (RBF) [54] , SVM [32] , decision tree (DT) or random forest (RF) [25,55] , and ANN [27] . Modern approaches based on deep learning can autonomously learn hierarchical representations from raw data, achieving superior performance on complex tasks. These include convolutional neural network (CNN) [24] , long short-term memory (LSTM) [56] , GNN [34] , GBT [35] , and a range of generative AI methods that have recently attracted considerable interest. Generative AI refers to AI models that learn patterns from training data to generate new content such as text, images, or designs. In the context of structural design, generative AI techniques are often employed in settings where specific design constraints or conditions are provided to guide the generation process, thereby aligning more closely with supervised learning frameworks. Representative generative AI models include variational autoencoder (VAE) [57] , GAN [33] , diffusion models [15] , and transformer or large language models (LLMs) [49,58] .

(3) RL learns through interactions with the environment. The algorithm (commonly referred to as an agent) executes actions at each step and receives feedback (rewards or penalties) from the environment. The objective is to learn a policy that maximizes the cumulative rewards. RL can be further categorized into model-based and model-free approaches. The former is exemplified by a Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) [59] , whereas the latter can be further divided into value- and policy-based methods. The former include Q-learning [60] and deep Q-networks [61] , whereas the latter include policy gradients and proximal policy optimization (PPO) [37] . Building on these methods, hybrid approaches, such as deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) [62] have also been developed.

Figure 2. Classification of data-driven AI methods in structural design.

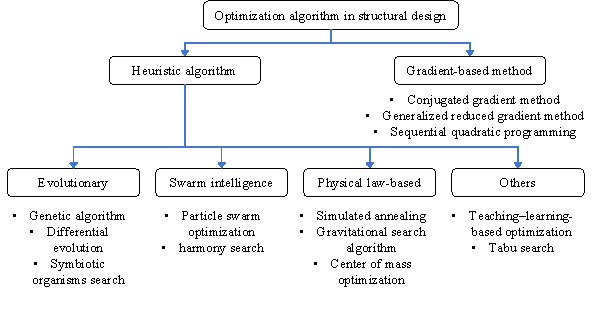

3.2 Optimization algorithms

Optimization algorithms are employed to efficiently determine the optimal solution under given objective functions and boundary conditions. Based on whether gradient computation is required, the optimization algorithms commonly used in structural design can be classified into heuristic algorithms and gradient-based methods, as illustrated in Figure 3.

(1) Heuristic algorithms can be further divided into four subcategories based on their sources of inspiration: a) evolutionary methods, including GA [24] , differential evolution (DE) [26] , and SOS [44] ; b) swarm-intelligence-based methods, including PSO [39] and harmony search (HS) [32] ; c) physics-based methods, including SA [45] , gravitational search algorithm (GSA) [63] , and center of mass optimization (CMO) [64] ; and d) other methods, including teaching-learning-based optimization [65] and tabu search [66] . Heuristic algorithms operate independently of specific problem structures, offering broad applicability, which makes them particularly effective for solving NP-hard problems in structural design [1] .

(2) In contrast, gradient-based methods are less commonly used. This category includes CGM [40] , generalized reduced gradient (GRG) method [67] , and SQP [41] . In scenarios involving highly nonlinear, implicit, or discontinuous constraints, the required gradient information is often difficult to compute or obtain, thereby limiting the practical application of these methods in engineering [2] .

Beyond these two major categories, certain optimization algorithms are tailored to specific problems. These include global optimization methods driven by surrogate models, such as EGO [28] , BO [42] , and DFMs [43] , and deterministic global optimization algorithms, such as DIRECT [30] . However, their applications remain relatively limited.

Figure 3. Classification of optimization algorithms in structural design.

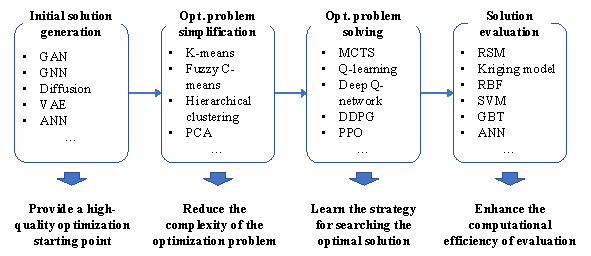

3.3 Role of data-driven AI

(1) Initial Solution Generation, where AI techniques are used to generate feasible and diverse starting designs, requiring models with strong generative capacity and sensitivity to design constraints. Commonly used AI methods include GAN [68] , GNN [69] , diffusion models [15] , and ANN [70] , which provide high-quality starting points for optimization.

(2) Optimization Problem Simplification, which involves reducing the dimensionality or complexity of the problem through methods such as clustering or feature selection, requiring efficient data abstraction and structural pattern recognition. K-means clustering [36] is frequently employed to reduce the number of optimization variables.

(3) Optimization Problem Solving, where AI methods are applied to learn optimal search strategies or policies, favoring algorithms with strong decision-making and learning capabilities, such as MCTS [59] , Q-learning [60] , and DDPG [62] .

(4) Solution Evaluation, which accelerates the performance assessment of candidate solutions using surrogate models with high inference efficiency and prediction accuracy. All supervised learning methods, particularly RSM [30] , Kriging models [71] , and ANN [64] , are widely applied to enhance the computational efficiency of performance assessment.

Figure 4. Role of data-driven AI methods in structural optimization.

Among these categories, solution evaluation represents the most widely studied application of AI in structural optimization, accounting for 67% of the reviewed literature. This is primarily because the evaluation stage, which typically involves computationally expensive numerical simulations, often becomes a bottleneck in the optimization process. Therefore, the following section will first provide a detailed discussion of how data-driven AI methods are applied in the evaluation stage, followed by their applications in other optimization stages.

4. Data-driven AI in evaluation stage of optimization

Expensive optimization problems are widely encountered in building structural designs. These problems are characterized by the high computational cost required to evaluate the objective functions and constraints, such as conducting large-scale high-fidelity numerical simulations [5] . To reduce the computational cost of such problems, data-driven AI is frequently employed in the evaluation stage of structural optimization to develop low-cost surrogate models that enable the rapid estimation of objective functions and constraints. These surrogate models must account for variations in structural characteristics and, in some cases, changes in loads or boundary conditions. Models trained for specific structural features are not suitable for structural optimization; therefore, they are beyond the scope of this study.

Depending on how these objectives and constraints are represented, AI surrogate models may adopt different prediction strategies to support efficient evaluation. AI surrogate models used to accelerate evaluation can be categorized into three types: (1) end-to-end prediction of objective functions and constraints; (2) end-to-end prediction of design metrics followed by computation of objective functions or constraints; and (3) a hybrid approach integrating multiple data-driven or physics-driven models, where design metrics are predicted in stages before deriving objective functions or constraints. Generally, the complexity and interpretability of these three types of surrogate models increase sequentially. A detailed introduction to each approach is provided below.

4.1 End-to-end prediction of objective functions and constraints

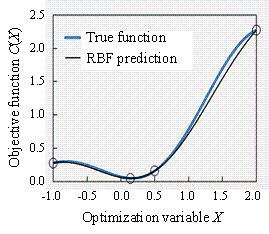

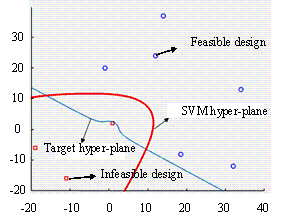

The most traditional and straightforward approach to constructing a surrogate model is to establish an end-to-end mapping between the optimization variables and objective functions or constraints, as illustrated in Figure 5. The relevant research findings are summarized in Table 2. The following section provides a detailed discussion of the prediction of the objective functions and constraints.

|

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 5. End-to-end prediction of objective functions and constraints. (a) Objective function prediction [67] . (b) Classification of constraints [72] .

(1) Objective function: When the relationship between the optimization variables and objective functions is relatively simple, end-to-end surrogate models can be highly effective. These models primarily utilize classical regression and interpolation methods, such as RSM [73] , which is generally equivalent to PR; GPR [74] , known as the Kriging model in geostatistics [75] ; and RBF [76] . The main advantages of these surrogate models are their simple construction and low computational cost, which render model training and updating computationally efficient. Consequently, they have been widely applied in structural optimization. For example, RSM has been used to optimize shear walls [77] , tensile [78] , and composite [79] structures. GPR and Kriging models have been applied in optimizing frame structures [28] , high-rise buildings [80] , and dampers [19,81] . On the other hand, RBF has been employed in the optimization of frame [54] , gridshell [67] , and frame-shear wall [67] structures.

(2) Constraints: In certain constrained optimization problems, the primary computational cost lies in determining whether a design satisfies the given constraints. In other words, the task of the surrogate model is transformed into a binary classification problem of either satisfying or violating the constraints. To address this issue, researchers have proposed the use of SVM, a classical classification model, primarily applied to optimizing truss structures [72] or individual structural components [82] . More recently, Cao et al. [16] introduced a vertex-based GNN classification model that captures the topological features of truss structures better than SVM. Similarly, Hore et al. [83] employed ANN to predict the collapse of frame structures; this can be regarded as a constraint classification task.

While end-to-end prediction of objective functions and constraints has demonstrated success in various applications, it nevertheless faces certain limitations. First, the direct mapping between the optimization variables and final outputs may be too complex to learn effectively, especially when the relationship involves multiple intermediate physical processes. Second, when either the objective functions or constraints change, the entire model must be retrained to reduce its flexibility and reusability. To address these challenges, alternative approaches have been proposed, which include predicting the intermediate design metrics first, and then computing the objective functions and constraints based on these predictions. This approach, which will be discussed in detail in the following section, offers several advantages in terms of model interpretability and adaptability.

Table 2. Summary of literature review on end-to-end prediction of objective functions and constraints.

|

Research |

Design object |

AI algorithm |

Optimization algorithm |

|

[28] |

Steel frame structure |

Kriging |

EGO |

|

[19,81] |

Damper |

Kriging |

EGO |

|

[84] |

Steel joint |

SVM |

GA |

|

[85] |

Shell structure |

Kriging |

EGO |

|

[71] |

RC frame structure |

Kriging |

Biogeography-based optimization |

|

[80] |

High-rise structure |

Kriging |

N/A |

|

[86] |

Damper |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[30] |

Steel frame structure |

RSM/RBF |

DIRECT |

|

[79] |

Composite structure |

RSM |

DIRECT |

|

[54] |

RC frame structure |

RBF |

N/A |

|

[77] |

Shear wall structure |

RSM |

PSO |

|

[26] |

GPR |

DE |

|

|

[67] |

Gridshell/frame-shear wall structure |

RBF |

GRG |

|

[87] |

High-rise structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[78] |

Tensile structure |

RSM |

PSO |

|

[88] |

Steel frame structure |

RSM/RBF/Kriging |

GA |

|

[89] |

Truss structure |

ANN |

PSO |

|

[3] |

Gridshell structure |

RSM |

GA |

|

[44] |

RC frame structure |

LightGBM |

SOS |

|

[16] |

Truss structure |

GNN |

PSO |

|

[32] |

Truss/gridshell structure |

SVM |

HS |

|

[72] |

Truss structure |

SVM |

SOS |

|

[82] |

Beam component |

SVM |

PSO |

|

[83] |

RC structure |

ANN |

N/A |

4.2 End-to-end prediction of design metrics

For structural optimization problems, objective functions and constraints are typically explicitly defined. Therefore, once all the necessary design metrics are obtained, the objective function values can be easily computed, and constraint satisfaction can be determined. Compared with directly predicting the objective functions and constraints end-to-end, a more common approach is to first predict the design metrics and then compute the objective functions and constraints, thereby reducing the complexity of the surrogate model*s prediction task. The relevant research findings are summarized in Table 3. Based on the characteristics of data representation, these approaches can be categorized into vector-based methods and other forms, as described below.

(1) Vector-based data representation (Figure 6(a)): A straightforward approach is to represent selected input features related to design metrics as an input vector, with the corresponding target design metrics used as the output vector. A data-driven surrogate model is then trained to map the relationship between these input and output vectors. The most commonly used methods for these surrogate models are ANN or multilayer perceptrons (MLPs). For example, ANNs have been used to predict the mechanical response of steel frame structures [64] , wind pressure on high-rise buildings [90] , natural frequencies of frame-core tube structures [91] , and construction costs of composite structures [92] . Additionally, some studies continue to utilize classical machine learning methods, such as RSM [93] , GPR [94] , Kriging models [95] , and SVM [96] .

At the same time, a range of modern machine learning methods has emerged. Among the most popular is GBT, which is an ensemble learning algorithm that iteratively builds a series of weak learners (such as DTs) to progressively minimize the loss function. For example, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) has been used to predict the load-carrying capacity of steel structures [35] ; light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM) has been used to estimate the fundamental period of RC structures [97] ; and categorical boosting (CatBoost) has been employed to predict the mechanical response of shear wall structures [39] . In general, regardless of whether ANNs, GBTs, or other data-driven algorithms are used, the fundamental task is to approximate the mapping between the input and output vectors. Consequently, determining the most suitable algorithm without experimental validation is challenging. Most studies train multiple algorithms on a given dataset and compare their performances to identify the most effective algorithm for a specific task [97每99] .

|

(a) |

|

(b) |

|

(c) |

Figure 6. Data representation methods of data-driven AI. (a) Vector-based data representation method [100] . (b) Image-based data representation method [101] . (c) Graph-based data representation method [47] .

(2) Alternative forms of data representation: Machine learning algorithms, such as ANN and GBT rely on vector-based input representations, requiring design information to be distilled into a set of key features. This vectorized approach not only imposes higher demands on feature selection, but also struggles to capture the topological connectivity between structural components. To address these limitations, researchers have proposed GNN-based surrogate models that leverage graph representations (Figure 6(c)). For example, frame structures have been represented as graphs, with GNNs applied for static or quasi-static structural analysis [13,102每104] . Similarly, shear wall structures have been modeled as graphs, with GNNs used to predict material consumption [105] . Building on this foundation, Kuo et al. [56] integrated GNNs with LSTM, enabling a dynamic structural analysis by fusing structural characteristics (graph embeddings) with seismic ground motion data (time-series inputs). Similarly, Li et al. [58] proposed an improved temporal fusion Transformer (TFT) architecture that combines structural features (static covariates) with seismic records (time-series data) to facilitate time-history analysis for different structural systems.

Table 3. Summary of literature review on end-to-end prediction of design metrics.

|

Research |

Design object |

AI algorithm |

Optimization algorithm |

|

[106] |

Steel frame structure |

Bayesian linear regression |

Charged system search |

|

[46,107] |

Truss structure |

RSM |

ViS-BLAST |

|

[93] |

Shell structure |

RSM |

N/A |

|

[108] |

Shell structure |

PR |

GA |

|

[109] |

High-rise structure |

RSM |

GA |

|

[17] |

Damper |

RSM |

N/A |

|

[110] |

Damper |

RSM |

CGM |

|

[111] |

Damper |

RSM |

DFM |

|

[43] |

Structural joint |

RSM |

DFM |

|

[31] |

Floor system |

PR |

N/A |

|

[94] |

Steel frame structure |

GPR |

GA |

|

[112] |

Truss structure |

Kriging |

N/A |

|

[113] |

High-rise structure |

Kriging |

N/A |

|

[114] |

High-rise structure |

Kriging |

SQP |

|

[115] |

High-rise structure |

Kriging |

GA |

|

[95] |

High-rise structure/damper |

Kriging |

N/A |

|

[116] |

Damper |

GPR |

GBM |

|

[18] |

Damper |

Kriging |

CMA-ES |

|

[117] |

Damper |

Kriging |

GA |

|

[29] |

Welding |

GPR |

GA |

|

[118] |

Structure |

GPR |

N/A |

|

[119] |

Steel frame structure |

RBF |

Random search strategy |

|

[120] |

High-rise structure |

RBF |

N/A |

|

[121] |

Steel frame structure |

SVM/ANN/LightGBM |

GA/PSO |

|

[63] |

RC frame structure |

SVM |

GSA |

|

[122] |

RC frame structure |

SVM |

N/A |

|

[123] |

Truss structure |

SVM |

PSO |

|

[124] |

Gridshell structure |

SVM/ANN |

N/A |

|

[96] |

Gridshell structure |

SVM |

PSO |

|

[66] |

Shear wall structure |

SVM |

Tabu search |

|

[65] |

Shear wall component |

SVM |

N/A |

|

[125] |

Masonry wall component |

ANN |

GA |

|

[12,126每128] |

Steel frame structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[129] |

Steel frame structure |

ANN/fuzzy logic |

N/A |

|

[130,131] |

Steel frame structure |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[132] |

Steel frame structure |

ANN |

Enhanced colliding bodies optimization |

|

[50] |

RC frame structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[133] |

RC frame structure |

ANN/RSM |

N/A |

|

[134] |

Truss structure |

ANN |

PSO |

|

[135] |

Truss structure |

ANN |

CMA-ES |

|

[27,136] |

Shear wall structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[91] |

Frame-core tube structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[90] |

High-rise structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[137] |

Low-rise structure |

ANN |

BO |

|

[138] |

Gridshell structure |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[139] |

FRP structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[92] |

Composite structure |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[140] |

Damper |

ANN |

GA |

|

[41] |

Damper |

ANN |

SQP |

|

[141] |

Damper |

ANN |

Adaptive immune memory cloning algorithm |

|

[45] |

Seismic isolation |

ANN |

SA |

|

[142] |

Seismic isolation |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[23] |

Tensile structure |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[13,103] |

Frame structure |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[102,104] |

Frame structure |

GNN |

GBM |

|

[56] |

Steel frame structure |

GNN/LSTM |

N/A |

|

[58] |

RC frame structure |

Transformer |

N/A |

|

[105] |

Shear wall structure |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[24] |

Aerial building machine |

CNN |

GA |

|

[143] |

High-rise structure |

LSTM/ANN |

N/A |

|

[97,98] |

RC frame structure |

LightGBM |

N/A |

|

[144] |

RC frame structure |

XGBoost/ANN |

GA |

|

[35] |

Steel structure |

XGBoost |

GA |

|

[99] |

High-rise structure |

GBRT |

N/A |

|

[20] |

High-rise structure |

LightGBM/GBRT |

PSO |

|

[25] |

Modular building |

DT |

N/A |

|

[39] |

Shear wall structure |

CatBoost/RF |

PSO |

|

[42] |

Seismic retrofitting |

XGBoost |

BO |

|

[145] |

Beam component |

CatBoost |

GA |

|

[146] |

Shear wall component |

XGBoost |

N/A |

4.3 Staged prediction of design metrics

For more complex cases, establishing an end-to-end data-driven surrogate model for the design metrics becomes challenging. In such situations, the evaluation task can be decomposed and addressed in stages by using different surrogate models. The relevant research findings are summarized in Table 4. Based on the task decomposition approach, staged prediction models can be categorized into three types.

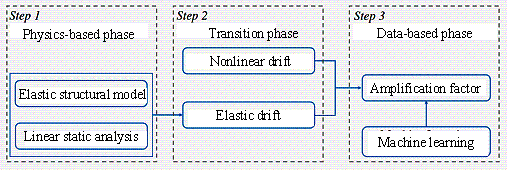

(1) Physics + data (Figure 7(a)): To improve the prediction of nonlinear responses, Guan et al. [147] proposed a two-stage ※physics-data§ hybrid prediction model. In this approach, a multi-degree-of-freedom (MDOF) model is first used to compute the elastic response, followed by an RF model to predict the nonlinear amplification factor, with some inputs derived from the elastic analysis results. Similarly, Zahra et al. [55] employed modal and elastic analyses to obtain intermediate results, which were subsequently used to establish a relationship between intermediate results and nonlinear displacements using an RF model.

(2) Data + physics (Figure 7(b)): To account for variations in both structural characteristics and loading conditions, Fei et al. [148] proposed a two-stage ※data-physics§ hybrid prediction model. In the first stage, a GNN is used to predict the story stiffness of an MDOF model for a given structural configuration. In the second stage, the MDOF model applies response spectrum analysis to consider different seismic loads. Similarly, Hu & Lei [149] introduced a three-stage ※data-data-physics§ hybrid prediction model. First, two ANNs are employed to predict the probabilistic dynamic response and complementary mode shapes, incorporating the influence of hysteretic behavior. Subsequently, an MDOF model is used to perform the mode combination method, considering the structural vibration mechanism. To estimate aerodynamic damping, which is difficult to predict directly, Chen et al. [38] proposed a two-stage ※data-physics & optimization§ hybrid prediction model. In the first stage, an ANN predicts a standard deviation response from pressure data as an intermediate result. In the second stage, a physics-based model is used to establish the relationship between the predicted standard deviation response and aerodynamic damping, which is then, solved using a GA.

(3) Data + data (Figure 7(c)): To predict the global damage index, which is difficult to directly estimate, Gholizadeh & Hasançebi [64] employed three ANNs. The first ANN predicts the maximum floor acceleration based on design variables. The second ANN predicts the maximum inter-story drift ratios based on design variables as well. Additionally, the third ANN uses both the design variables and predicted maximum inter-story drift ratios to estimate the global damage index. To improve the accuracy of engineering demand parameter (EDP) predictions for braced frame structures, Fang et al. [150] first used LightGBM to classify design cases as compliant or non-compliant. For compliant cases, various regression models were applied to predict the EDP values. Similarly, Zhao et al. [151] adopted an active-learning extended-support vector regression (AL-X-SVR) surrogate model to optimize both structural reliability and embodied carbon constraints, achieving a balance between performance and environmental sustainability.

Table 4. Summary of literature review on staged prediction of design metrics.

|

Research |

Design object |

AI algorithm |

Optimization algorithm |

|

[147] |

Steel frame structure |

RF |

N/A |

|

[55] |

Steel frame structure |

RF |

N/A |

|

[148] |

Shear wall structure |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[149] |

Braced frame structure |

ANN |

GA |

|

[38] |

High-rise structure |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[64] |

Steel frame structure |

ANN |

CMO |

|

[150] |

Braced frame structure |

LightGBM/XGBoost/GBDT |

N/A |

|

[151] |

Engineering structure |

AL-X-SVR |

N/A |

|

(a) |

|

(b) |

|

(c) |

Figure 7. Staged prediction of design metrics. (a) Physics + data [147] . (b) Data + physics [38] . (c) Data + data [64] .

5. Data-driven AI in other stages of optimization

5.1 Learn to generate initial design

In structural optimization, an initial design is required as the starting point for the optimization process. A well-designed initial solution can significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of optimization algorithms in finding an optimal design that meets specified requirements. With the recent advances in deep learning technologies, an end-to-end structural design paradigm, known as the intelligent generation method [48] , has emerged. This approach leverages data-driven models to directly map input data, such as architectural designs, design conditions, and existing structural designs, to output data, thereby generating structural designs from scratch. Compared to intelligent optimization methods, intelligent generation methods offer the advantage of high efficiency, as trained models can generate design solutions within seconds. However, a key limitation is that the generated designs may not strictly satisfy all design constraints, owing to the inherent approximation nature of data-driven models. To address this issue, an effective strategy is to first use intelligent generation methods to produce a reasonable initial design (from nothing to something) and then refine it using intelligent optimization methods to enhance the structural performance, such as safety and cost-effectiveness (from something to optimal). The relevant research findings are summarized in Table 5. Based on data representation characteristics, intelligent generation methods can be categorized into vector-, image-, and graph-based approaches.

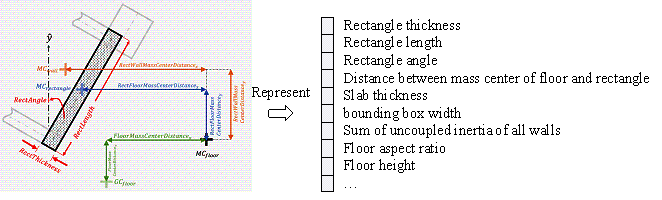

(1) Vector-based data representation (Figure 6(a)): While structural design involves numerous factors, only a limited set of key parameters typically have a decisive impact on the final design. Researchers can leverage their understanding of structural design to select these critical parameters as input vectors, and apply correlation analysis and other techniques to establish the relationship between the input vector and structural design. ANNs are the most commonly used models in this field, and have been applied to learn and generate initial designs for various structures, including truss structures [152] , shear wall structures [70,100] , and dampers [153,154] . A key aspect of this approach is feature selection (feature engineering), which directly influences the model performance. Typically, ANN input feature vectors range from a few to a dozen parameters, thereby providing limited design information. However, with meticulous feature engineering, researchers have successfully constructed ANN models with 334 input features [70] , demonstrating the potential of ANNs in handling high-dimensional design problems.

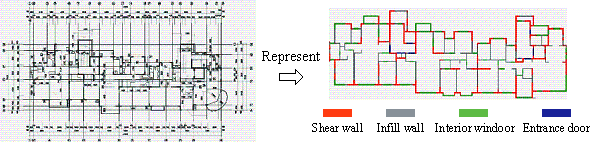

(2) Image-based data representation (Figure 6(b)): In certain structural design tasks, spatial information, such as the layout and geometric configuration of components, is crucial. For example, when determining the structural layout, considering the spatial relationships between the architectural and structural components is necessary. For such tasks, data can be represented in the form of images, which are essentially 2D matrices with multiple channels, allowing convolutional kernels to extract high-dimensional features from the images. Naturally, CNNs are well-suited for solving image-based structural design problems. Furthermore, generative AI models designed for image processing, which also rely on convolutional operations, often outperform traditional CNNs, and have demonstrated superior effectiveness in various structural design applications. For example, VAEs have been used to design shell structures [155] and vibration isolation metastructures [57] . GANs have been applied to the design of shear wall structures [101] , frame-core tube structures [156] , braced frame structures [157] , floor systems [158] , seismic isolation [159] , and structural joints [33] . Additionally, diffusion models have been employed to design shear wall structures [15,160,161] . Given the critical role of domain knowledge in structural design, some studies have incorporated physical rules [68,162] and empirical design rules [156] into generative AI models, further enhancing the quality and practicality of the generated designs.

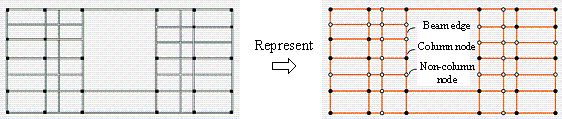

(3) Graph-based data representation (Figure 6(c)): In certain structural design tasks, topological information such as the connectivity and types of structural components, is crucial. For example, when designing the cross-sectional dimensions of a structural component, considering the internal forces transmitted from connected components is essential. For such tasks, data can be represented in the form of graphs, consisting of a set of nodes and edges, with GNNs applied for learning and prediction directly on these graph representations. This representation is particularly well-suited for frame, truss, and grid structures, where the connections between the components can be intuitively modeled as a graph. Recent studies have successfully utilized GNNs for various structural design applications. For instance, GNNs have been employed in form-finding [22] and joint design [163] of gridshell structures. In frame structures, GNNs have been used for beam layout [164] , cross-sectional [104] , and steel reinforcement [165] designs. Additionally, graph representations can also be applied to non-bar structural components, such as shear walls, to encode their layout information. For example, researchers have utilized GNNs to design the layouts of shear walls [69] and corresponding beams [34] .

The choice of data representation depends on the specific characteristics of the design task, and multiple representation methods can be combined to enhance the effectiveness. For example, to achieve the topology design of frame structures, Zhang et al. [47] first employed an image-based representation, using a GAN to generate images containing column and non-column nodes. Subsequently, a graph-based representation was used, in which another GAN generated an adjacency matrix that defined the beam connections.

Table 5. Summary of literature review on initial design generation.

|

Research |

Design object |

AI algorithm |

Optimization algorithm |

|

[152] |

Truss structure/beam component |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[70,100] |

Shear wall structure |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[154] |

Damper |

ANN |

N/A |

|

[153] |

Damper |

SVM/ANN |

GA |

|

[166] |

Damper |

Fuzzy logic/cluster |

N/A |

|

[155] |

Shell structure |

VAE |

GA |

|

[57] |

Vibration isolation metastructure |

VAE/ANN |

Adaptive moment estimation |

|

[68,101,167每170] |

Shear wall structure |

GAN |

N/A |

|

[49] |

Shear wall structure |

GAN |

GA/online learning |

|

[171] |

Shear wall structure |

GAN |

GA |

|

[157,162] |

Braced frame structure |

GAN |

N/A |

|

[156] |

Frame-core tube structure |

GAN |

N/A |

|

[158] |

Floor system |

GAN |

N/A |

|

[172] |

Shear wall structure |

GAN/CNN |

N/A |

|

[33] |

Structural joint |

GAN |

N/A |

|

[159] |

Seismic isolation |

GAN |

N/A |

|

[15,160,161] |

Shear wall structure |

Diffusion model |

N/A |

|

[104,164] |

Frame structure |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[22,163] |

Gridshell structure |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[34] |

Shear wall structure (Beam system) |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[69,173] |

Shear wall structure |

GNN |

N/A |

|

[165] |

Rebar |

GNN |

GA |

|

Frame structure |

GAN/GNN |

N/A |

5.2 Learn to reduce problem complexity

Structural design typically involves many design elements, and requires the determination of the spatial positions and cross-sectional dimensions of hundreds of structural components. To reduce the complexities of both design and construction, simplifying the problem appropriately is necessary. Unsupervised learning algorithms, including clustering and dimensionality reduction, can effectively extract the underlying patterns and features from data, thereby reducing the complexity of optimization problems. The relevant research findings are summarized in Table 6. In structural optimization, unsupervised learning can serve multiple purposes, as discussed in the following sections.

(1) Optimization variable definition: The complexity of an optimization problem is highly dependent on the number of optimization variables. By clustering similar design elements (e.g., symmetry), the number of variables can be significantly reduced, thereby simplifying the optimization process. For example, Qin et al. [49] and Zhang et al. [36] applied K-means clustering in the design of shear wall layout and modular structure topology optimization, respectively, to automatically group similar optimization elements into clusters, which effectively reduced the problem complexity.

(2) Surrogate model construction: In intelligent optimization, surrogate models are frequently used during the evaluation stage, and unsupervised algorithms can further reduce the complexity of surrogate model development. For example, Cer豕 et al. [50] applied PCA to reduce the dimensionality of training data, thereby decreasing the fitting complexity of ANNs. Balaghi et al. [52] employed the fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm to group structural components, thus improving the accuracy of response predictions. Similarly, Zhang et al. [88] used K-means clustering to classify datasets and trained separate surrogate models for each cluster, thereby reducing the overall model construction complexity.

(3) Design-parameter merging: To reduce construction complexity and costs, structural design often requires merging design parameters of components and joints. Clustering algorithms are particularly effective in this regard. For example, the K-means algorithm has been applied to merge nodes and members in space frame structures [21,40] , and group cross-sections in RC frame structures [51] .

Evidently, unsupervised algorithms play a crucial role in reducing the complexity throughout the intelligent optimization process.

Table 6. Summary of literature review on optimization problem simplification.

|

Research |

Design object |

AI algorithm |

Optimization algorithm |

|

[21,40] |

Space frame structure |

K-means |

CGM |

|

[49] |

Shear wall structure |

K-means |

GA/online learning |

|

[36] |

Modular structure |

K-means |

Solid isotropic material with penalization |

|

[51] |

RC frame structure |

K-means |

GA |

|

[88] |

Steel frame structure |

K-means |

GA |

|

[50] |

RC frame structure |

PCA |

GA |

|

[52] |

Frame/truss structure |

Fuzzy C-means |

GA |

5.3 Learn to find optimal solution

For a given optimization problem, which includes optimization variables, objective functions, and boundary conditions, the role of an optimization algorithm is to identify the optimal combination of variables that maximizes or minimizes the objective function, while satisfying the boundary constraints. Because real-world optimization problems are often highly complex and nonconvex, various optimization algorithms have been developed (Figure 3), each employing different strategies to search for optimal solutions. Not possessing prior knowledge of the problem to be solved, traditional optimization algorithms rely on a repeated trial-and-error process to determine the search direction, which typically requires hundreds of performance evaluations. Moreover, the knowledge gained from this trial-and-error process cannot be retained, implying that the same process must be repeated when solving a new problem. This limitation significantly affects the optimization efficiency. RL offers a potential solution to this problem. By formulating a structural design as a Markov decision process, RL agents can retain the experience accumulated during the trial-and-error process in the form of neural network parameters, thus enabling them to learn an optimal search strategy. Once trained, an RL agent can approximate an optimal solution in only a few iterations, thereby dramatically improving design efficiency. The relevant research findings are summarized in Table 7.

Unlike supervised learning, RL does not rely on labeled data; instead, it learns through feedback obtained from an agent*s interaction with the environment. This characteristic implies that RL typically requires a significantly larger amount of data than does supervised learning, thus placing high demands on the feedback generation efficiency within the environment. Consequently, RL has primarily been applied to the design of frame and truss structures, where computation and analysis are relatively simple and efficient. For example, Luo et al. [59,174] and Li et al. [37] employed MCTS and PPO, respectively, for truss layout design. Hayashi & Ohsaki [175,176] represented structural information as graphs and used graph embeddings combined with Q-learning for truss topology and steel frame sizing optimization. Fu et al. [14] represented structural information as tensors and leveraged CNN-based convolutional feature extraction within the ※Actor-Critic framework§ for steel frame sizing design. In addition to structural layout and sizing, RL has been applied to other tasks in well-defined environments. For instance, Liu et al. [60] and Jeong & Jo [62] focused on reinforcement collision detection in RC structures and beam section designs, respectively, and proposed methods based on Q-learning and DDPG. For optimization problems involving complex computational environments, RL typically requires the assistance of surrogate models to enhance efficiency. For example, in the aerodynamic optimization of high-rise buildings, Li et al. [143] introduced a surrogate model based on transfer learning and meta-learning, thereby enabling the effective training of a DDPG-based RL agent.

Table 7. Summary of literature review on optimization problem solving.

|

Research |

Design object |

AI algorithm |

Optimization algorithm |

|

[37] |

Truss structure |

PPO |

N/A |

|

[59,174] |

Truss structure |

MCTS |

N/A |

|

[175] |

Truss structure |

Q-learning |

N/A |

|

[14] |

Steel frame structure |

Actor-Critic |

N/A |

|

[176] |

Steel frame structure |

Q-learning |

N/A |

|

[61] |

Steel frame structure |

DQN |

SA/PSO |

|

[143] |

High-rise structure |

DDPG |

N/A |

|

[62] |

Beam component |

DDPG |

N/A |

|

[60] |

Rebar |

Q-learning |

N/A |

|

[177] |

Gridshell structure |

Graph embedding/Q-learning |

N/A |

6. Discussion

6.1 Development trends

Optimization remains a perennial research focus, with its applications becoming increasingly widespread in structural design. In recent years, the rapid advancement of data-driven methodologies has significantly enhanced the intelligence of structural optimization, exhibiting the following developmental trends:

(1) Generalization capacity: The generalization capability of AI surrogate models in the intelligent optimization evaluation stage has been increasingly enhanced; it has evolved from applicability to individual structural cases to broader structural categories. As the variability within a single structural case is limited, AI surrogate models tailored for specific cases are relatively easy to establish, with input data derived from case-specific design variables. However, when encountering new optimization cases, these models become inapplicable, necessitating the reconstruction of surrogate models and repetition of processes, such as sampling, dataset generation, and model training. This limitation constrains the computational time savings achievable with case-specific AI surrogate models and hampers their practical engineering applications. For instance, in two recent studies, AI surrogate models achieved computational time savings of 30% [66] and 26% [91] . To address this challenge, researchers have proposed general surrogate models applicable to specific structural categories, which, once trained, can be directly applied to new optimization cases within the designated category without the need for model reconstruction. For example, staged prediction has been employed to develop general surrogate models for the mechanical response of frame-braced structures [149] and shear wall structures [148] . Additionally, based on GNN, general surrogate models have been proposed for the mechanical response of frame structures [103] and for material consumption in shear wall structures [105] . These general surrogate models, tailored for specific structural categories, hold promise for further enhancing the computational efficiency of intelligent optimization.

(2) Functional expansion: The roles of data-driven algorithms in structural optimization have become increasingly diverse, expanding from merely accelerating the evaluation stage to encompassing all stages of optimization. As the evaluation stage is typically the most time-consuming part of structural optimization, particularly for computationally expensive problems, the use of AI surrogate models with high inference efficiency to accelerate evaluation has been a natural research direction, explored as early as the last century [12] . In recent years, following the success of AlphaGo in surpassing top human experts in the game of Go [178] and the revolutionary advancements in Stable Diffusion in high-quality image generation [179] , researchers have increasingly investigated RL-based structural optimization [59,175] and generative AI-based end-to-end structural design [15,161] . In essence, both methodologies can be regarded as an integral part of intelligent optimization, whereby RL is employed to learn optimal solution strategies, while generative AI facilitates the generation of initial designs as starting points for optimization (Figure 4). Additionally, although unsupervised learning has received relatively less attention, it also plays an irreplaceable role in structural optimization. As data-driven algorithms are increasingly integrated into various stages of the optimization process, the level of intelligence in structural optimization continues to advance.

(3) Data representation: The representation methods used in data-driven algorithms have become increasingly diverse, evolving from vector-based approaches to image- and graph-based representations. Traditional vector-based methods rely heavily on feature engineering and are constrained by the limited number of features they can handle, typically ranging from a few to a dozen, which poses challenges for high-dimensional problems. In contrast, image- and graph-based representation methods can efficiently process high-dimensional data. For instance, GANs can generate images with resolutions of 256 ℅ 256 ℅ 3 [167] , while GNNs can manage graphs comprising hundreds or even thousands of nodes and edges [47] . Moreover, image- and graph-based methods offer the following distinct advantages: (a) Images are well-suited for capturing spatial relationships, whereas graphs excel in representing topological relationships; both are critical in structural design. (b) By selecting appropriate data representation methods tailored to specific tasks, the complexity of AI learning can be reduced, while the latest advancements in generative AI and related technologies can be leveraged to further enhance the performance of data-driven algorithms.

(4) Model credibility: The credibility of data-driven algorithms has been steadily improving, transitioning from purely black-box models to interpretable machine learning and knowledge-enhanced AI. The black-box nature of these algorithms has raised concerns regarding their applicability in industries, such as civil engineering. Consequently, extensive research has been devoted to enhancing model transparency and reliability. For instance, Latif et al. [144] applied the widely used SHAP tool [180] to a trained XGBoost model, identifying the contributions of various input features to the prediction of fundamental vibration periods. Once the impact of each input feature is understood, XGBoost becomes nearly as interpretable as traditional empirically defined formulas. Additionally, incorporating domain knowledge into deep learning has been shown to enhance model performance and reduce errors. For example, Lu et al. [68] and Fu et al. [14] introduced mechanical response constraints into AI training through surrogate models, while Fei et al. [156] and Fu et al. [162] embedded design rule constraints by constructing loss functions with uninterrupted gradients. As the credibility of data-driven algorithms continues to improve, they are expected to gain wider acceptance among design and research professionals in structural engineering.

6.2 Challenges and outlook

Further developments in data-driven intelligent optimization algorithms face several key challenges:

(1) Integration of data-driven algorithms with optimization algorithms to overcome the limitations of traditional optimization methods. Analyzing the roles of data-driven approaches in structural optimization (Figure 4) reveals that their ultimate effect can be summarized as ※acceleration,§ enabling the rapid identification of feasible design solutions [181] . Optimization efficiency is crucial in engineering practice and significantly enhances the application potential of intelligent optimization. However, advances in computing technology and reductions in computational costs may render the cost of traditional optimization algorithms acceptable in the future. This raises the fundamental question of whether intelligent optimization can achieve what traditional optimization algorithms cannot. For instance, can intelligent optimization consistently surpass the highest levels of human-designed solutions? To achieve this goal, further exploration is required on the integration of data-driven algorithms with optimization techniques. For example, the design process can be decomposed by utilizing generative AI methods for the empirical rule-based phase, while applying optimization algorithms for the physics-based phase [182] . Additionally, generative AI can be employed in optimization iterations to generate candidate solutions instead of traditional evolutionary operators [183] . Furthermore, optimization can be conducted within the latent space of generative AI models, rather than directly on explicit design variables [57,184] .

(2) Obtaining high-quality datasets to train more effective data-driven algorithms. The performance of data-driven algorithms inherently depends on the quality of datasets used for training. In structural design tasks, constructing high-quality datasets presents several challenges, as listed below.

2.1) Data authenticity: Structural design is a highly non-standardized process, where each engineering project is uniquely tailored by engineers. Consequently, synthetically generated data often lack the complexity and richness found in real-world data. AI models trained on synthetic datasets may fail to perform as expected when applied to real-world scenarios.

2.2) Dataset size: Given the limitations of synthetic data, real-world data collection is often necessary. However, owing to issues, such as copyright and privacy concerns, obtaining authentic structural design data is challenging, which results in small dataset sizes that may hinder the generalization capability of AI models.

2.3) Design quality of data: Structural design is inherently creative, with no single optimal solution. Designs are typically required to balance safety and economic efficiency. As a result, both real and synthetic datasets may include designs of varying quality, where lower-quality designs could negatively impact AI performance.

2.4) Dataset distribution: Real-world datasets often exhibit long-tail distributions, where some design conditions are well-represented, while others are underrepresented. This imbalance can lead to inadequate training in underrepresented scenarios, resulting in suboptimal AI performance for rare design conditions.

To address the challenges, further exploration is needed on how optimization algorithms can enhance data quality. One potential approach is training generative AI models on optimized structural design datasets [171] .

(3) Application of LLMs and other advanced intelligent technologies for intelligent optimization. LLMs are generative AI models trained on extensive textual data that enable them to comprehend and generate natural language text. Their applications are rapidly expanding and demonstrating significant potential in areas, such as architectural design [185每188] and construction [189] . However, the application of LLMs in structural design and optimization remains highly limited. To the best of our knowledge, their use in this domain has been restricted to: 1) utilizing LLMs to interpret user commands and coordinate other AI and optimization modules [49] ; and 2) employing LLMs for finite element analysis, design parameter adjustment, and sensitivity analysis [190] . Multimodal foundation models, which integrate LLMs with large-scale vision models, are capable of processing and understanding diverse data types, including text and images. Given that structural design heavily involves both textual information (e.g., codes, design specifications, and client requirements) and visual data (e.g., multidisciplinary design drawings), further exploration is warranted to investigate how LLMs and multimodal models can be effectively applied in intelligent optimization.

7. Conclusions

Intelligent optimization is a novel approach based on data-driven AI, characterized by its ability to ※learn§ and ※remember.§ In the field of building structural design, intelligent optimization algorithms incorporate a wide range of AI techniques, including unsupervised and supervised learning (including generative AI), learning, and all types of RL. The optimization algorithms employed are primarily heuristic methods.

Based on the stage within the optimization process, the role of data-driven AI can be categorized into four types: initial solution generation, optimization problem simplification, optimization problem solving, and solution evaluation. For initial solution generation, various data representation methods have been explored, including vector-, image-, and graph-based approaches. Notably, deep learning models, such as GANs, diffusion models, and GNNs have demonstrated impressive performance in this area. For optimization-problem simplification and solving, the existing research has primarily leveraged unsupervised learning and RL methods. Although few studies have been published in these areas, these methods play an irreplaceable role in improving optimization efficiency. For solution evaluation, different AI-based approaches have been adopted, including end-to-end prediction of objective functions, constraints, and design metrics, and staged prediction of design metrics. The complexity of AI model construction and its interpretability has increased progressively across these approaches.

With the continued advancement of research on intelligent optimization methods, several emerging trends can be observed; for example, the generalization capability of data-driven models in structural optimization is increasingly enhanced; their roles are becoming more diverse; their representation methods are expanding; and their reliability is steadily improving. To further develop intelligent optimization, future efforts should focus on exploring novel integration approaches between data-driven algorithms and optimization methods, addressing the scarcity of high-quality training data, and investigating the application of large language models and other cutting-edge AI technologies in structural optimization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sizhong Qin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing 每 original draft, Writing 每 review and editing. Yifan Fei: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing 每 original draft. Wenjie Liao: Resources, Supervision, Writing 每 review and editing. Xinzheng Lu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Resources, Writing 每 review & editing.

Acknowledgements

References

[1] Afzal M, Liu YH, Cheng JCP, et al. Reinforced concrete structural design optimization: a critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020; 260: 120623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120623.

[2] Aldwaik M, Adeli H. Advances in optimization of highrise building structures. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2014; 50: 899每919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-014-1148-1.

[3] Gantovnik VB, Anderson-Cook CM, G邦rdal Z, et al. A genetic algorithm with memory for mixed discrete每continuous design optimization. Computers & Structures 2003; 81: 2003每9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7949(03)00253-0.

[4] Li J-Y, Zhan Z-H, Zhang J. Evolutionary computation for expensive optimization: a survey. Machine Intelligence Research 2022; 19: 3每23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11633-022-1317-4.

[5] He CL, Zhang Y, Gong DW, et al. A review of surrogate-assisted evolutionary algorithms for expensive optimization problems. Expert Systems with Applications 2023; 217: 119495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119495.

[6] Negrin I, Kripka M, Yepes V. Metamodel-assisted design optimization in the field of structural engineering: a literature review. Structures 2023; 52: 609每31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.04.006.

[7] Picard C, Regenwetter L, Nobari AH, et al. Generative optimization: A perspective on AI-enhanced problem solving in engineering 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.13281.

[8] Ramu P, Thananjayan P, Acar E, et al. A survey of machine learning techniques in structural and multidisciplinary optimization. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2022; 65: 266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-022-03369-9.

[9] Vlah D, Kastrin A, Povh J, et al. Data-driven engineering design: A systematic review using scientometric approach. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2022; 54: 101774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2022.101774.

[10] Soori M, Jough FKG. Artificial intelligent in optimization of steel moment frame structures: A review. International Journal of Structural and Construction Engineering 2024; 18: 141每58.

[11] Kookalani S, Parn E, Brilakis I, et al. Trajectory of building and structural design automation from generative design towards the integration of deep generative models and optimization: A review. Journal of Building Engineering 2024; 97: 110972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110972.

[12] Jenkins WM. On the application of natural algorithms to structural design optimization. Engineering Structures 1997; 19: 302每8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-0296(96)00074-0.

[13] Chou Y-T, Chang W-T, Jean JG, et al. StructGNN: an efficient graph neural network framework for static structural analysis. Computers & Structures 2024; 299: 107385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2024.107385.

[14] Fu BC, Gao YQ, Wang W. A physics-informed deep reinforcement learning framework for autonomous steel frame structure design. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2024; 39: 3125每44. https://doi.org/10.1111/mice.13276.

[15] Gu Y, Huang Y, Liao W, et al. Intelligent design of shear wall layout based on diffusion models. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2024; 39: 3610每25. https://doi.org/10.1111/mice.13236.

[16] Cao HY, Li M, Nie LL, et al. Vertex-based graph neural network classification model considering structural topological features for structural optimization. Computers & Structures 2024; 305: 107542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2024.107542.

[17] Lan X, Wei GL, Zhang XX. Study on the influence and optimization design of viscous damper parameters on the damping efficiency of frame shear wall structure. Buildings 2024; 14: 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020497.

[18] Nasab MSE, Kim J. Reliability-based optimum distribution of seismic energy dissipation devices in fuzzy structural systems using meta-models. Engineering Structures 2023; 278: 115502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115502.

[19] Fadel Miguel LF, Elias S, Beck AT. Reliability-based optimization of supported pendulum TMDs* nonlinear track shape using Pad谷 approximants. Engineering Structures 2024; 306: 117861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.117861.

[20] Kong QZ, Liu JX, Wu X, et al. Seismic fragility estimation based on machine learning and particle swarm optimization. Buildings 2024; 14: 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14051263.

[21] Bi MH, Liu YP, Xu T, et al. Clustering and optimization of nodes, beams and panels for cost-effective fabrication of free-form surfaces. Engineering Structures 2024; 307: 117912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.117912.

[22] Favilli A, Laccone F, Cignoni P, et al. Geometric deep learning for statics-aware grid shells. Computers & Structures 2024; 292: 107238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2023.107238.

[23] Rizzo F, Caracoglia L. Examination of artificial neural networks to predict wind-induced displacements of cable net roofs. Engineering Structures 2021; 245: 112956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112956.

[24] Wang JQ, Chen K, Yang H, et al. Ensemble deep learning enabled multi-condition generative design of aerial building machine considering uncertainties. Automation in Construction 2024; 157: 105134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105134.

[25] Tusnin AR, Alekseytsev AV, Tusnina O. Using machine learning technologies to design modular buildings. Buildings 2024; 14: 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072213.

[26] Xiao YJ, Yue F, Zhang XA, et al. Aseismic optimization of mega-sub controlled structures based on Gaussian process surrogate model. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2022; 26: 2246每58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-022-0832-8.

[27] Alanani M, Brown T, Elshaer A. Multiobjective structural layout optimization of tall buildings subjected to dynamic wind loads. Journal of Structural Engineering 2024; 150: 04024069. https://doi.org/10.1061/JSENDH.STENG-12366.

[28] Peng CL, Guo T, Chen C, et al. A real-time hybrid simulation framework for reliability-based design optimization of structures subjected to pulse-like ground motions. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2024; 53: 3246每62. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.4175.

[29] Wang L, Qian XD. Optimization-improved thermal每mechanical simulation of welding residual stresses in welded connections. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2024; 39: 1275每93. https://doi.org/10.1111/mice.13136.

[30] Wan YY, Hu B, Yang Y, et al. Discrete sizing optimization method based on dividing rectangles algorithm and local response surface for steel frame structures. Journal of Building Engineering 2023; 79: 107826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107826.

[31] Broyles JM, Gevaudan JP, Hopper MW, et al. Equations for early-stage design embodied carbon estimation for concrete floors of varying loading and strength. Engineering Structures 2024; 301: 117369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.117369.

[32] Cao HY, Li HY, Sun W, et al. A boundary identification approach for the feasible space of structural optimization using a virtual sampling technique-based support vector machine. Computers & Structures 2023; 287: 107118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2023.107118.

[33] Du WF, An YL, Xue HJ, et al. Generation and evaluation of unimaginable three-dimensional structural joints using generative adversarial networks. Automation in Construction 2024; 167: 105707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105707.

[34] Zhao PJ, Liao W, Huang YL, et al. Beam layout design of shear wall structures based on graph neural networks. Automation in Construction 2024; 158: 105223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105223.

[35] Truong V-H, Cao T-S, Tangaramvong S. A robust machine learning-based framework for handling time-consuming constraints for bi-objective optimization of nonlinear steel structures. Structures 2024; 62: 106226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106226.

[36] Zhang ZX, Jiang LM, Yarlagadda T, et al. A novel multi-pattern control for topology optimization to balance form and performance needs. Engineering Structures 2024; 303: 117581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.117581.

[37] Li MS, Zheng Q, Ashuri B. Application of artificial intelligence in design automation: a two-stage framework for structure configuration and design. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2024; 150: 04024083. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-14409.

[38] Chen ZS, Zhang LK, Li K, et al. Machine-learning prediction of aerodynamic damping for buildings and structures undergoing flow-induced vibrations. Journal of Building Engineering 2023; 63: 105374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105374.

[39] Li Y, Liu YK, Yu HF, et al. Multi-objective optimization design of coupled wall structure with hybrid coupling beams using hybrid machine learning algorithms. Journal of Building Engineering 2023; 78: 107745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107745.